Park, 68, is one of hundreds of Koreans returning to the country of their ancestors after being stranded on the island since the end of World War II.

"I have waited to come here my whole life. My [late] husband said he would even walk across the water from Sakhalin to Korea if he could."

About 150,000 Koreans made their way to Sakhalin in the early 1940s, at a time when Japan ruled Korea as a colony and held the lower half of Sakhalin.

The Koreans -- some forced into working for the Japanese army and others desperate for jobs -- ended up in backbreaking labor at Japanese-run coal mines, lumber yards and pulp mills.

When the war ended, many found their way to Japan or to North Korea. About one-third, most of them with family in what became South Korea, were left behind, stateless.

Their Japanese nationality was gone, the Soviets did not claim them, and Moscow was not about to send them home to a U.S.-backed state.

"My parents didn't go to Sakhalin with thoughts of staying." said Lee Mi-sook, 67, who returned to South Korea on Oct. 18.

"They needed money and were planning to work for three or five years. But the doors slammed shut and they ended up getting stuck there," said Lee, who left a son behind in Russia.

Lee and her husband, who speak Russian at home, now live in a small but modern apartment about an hour west of Seoul. It took years of negotiations among Japan, Russia and South Korea to devise a repatriation plan.

Japan, which says all its compensation claims with South Korea were settled by an accord the two signed decades ago, has quietly and on humanitarian grounds helped fund the return, South Korea's Overseas Information Service said.

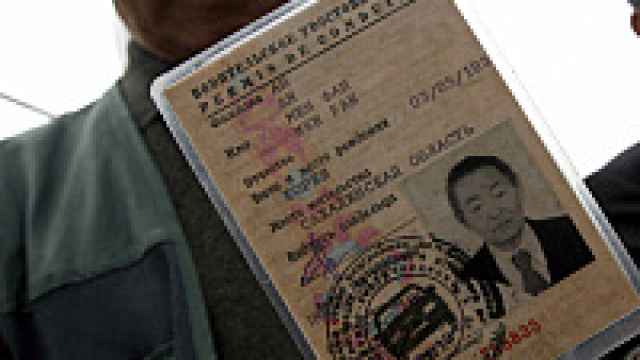

Han Jae-ho / Reuters Ahn Maeng-hwan, 76, displaying the driver's license he used in Sakhalin. | |

The first group of 900 Sakhalin Koreans came back in 2000. The current program, open to Koreans 65 and older, has been relocating another 610 people since the start of October.

"My parents wanted to come back so much. They spent their days crying until they finally passed away," said Chung Young-ja, 67, who went with her parents to Sakhalin when she was a toddler.

South Korea says there are still 3,200 first-generation Koreans on Sakhalin.

On leaving Russia, Chung and her husband, Chang Jung-gi, left behind three children and seven grandchildren who are settled in the country and are never likely to live in South Korea.

Among the pictures they brought back from Sakhalin is one of a memorial stone to the Koreans who waited in vain at a harbor for a refugee ship to take them home.

"Our parents waited there for years and years but the ship never came. They missed their homes so much," Chang said.

After about 15 years of being stateless, many of the Koreans left for North Korea in the early 1960s, when the Communist state was economically more advanced than the South.

New arrival Lee Mi-sook said, "My heart finally feels like it is at home."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.