Speaking to American talk show host Charlie Rose in a segment that aired last weekend, Russian President Vladimir Putin offered his own recipe for wise leadership: identify problems in time and react accordingly.

Viewed through the prism of events in eastern Ukraine, this looks very much like retrospective wisdom. After more than a year of improvising a policy in Donetsk and Luhansk, Putin seems to be looking for a way out. Syria is helping, for now at least, by drawing attention away from Ukraine. But he cannot wish the problem away.

Indeed, Putin's task on the ground in Ukraine is becoming more complicated. If Russia really wants to pull out, it has to wind up a small but stubborn political local leadership and a quite large militia structure of at least 20,000 fighters that it has generously equipped with artillery and heavy armor.

It will discover, if it has not done so already, that separatist leaders have developed their own, usually corrupt, interests, and may not go quietly, and that fighters, abandoned to their own resources, may turn to crime.

Putin will also eventually have to clear up with the separatist entities the situation along Russia's own border, which has turned into a flourishing center for contraband. For now, managing Russian domestic opinion may seem easy. But the day is approaching when Putin will have to explain to his own people why the glorious revolution in the east turned into what most would call just another bardak. A mess.

The Kremlin has begun to take action in the last few months, stepping up pressure on its allies in the east. There have been changes in the separatist leadership. Obstreperous military commanders have been squeezed out. More recently the second-ranking leader of the Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) — Andrei Purgin, firmly opposed to compromise with Kiev — was abruptly arrested and detained by Donetsk's Ministry of State Security (MGB).

Separatist leaders say reorganization of the Donetsk military forces has replaced local warlords, Cossacks and others, with regular officers. The large units that reported directly to top leaders — DPR head Alexander Zakharchenko, or Security Council secretary Alexander Khodakovsky — have, in theory at least, been subordinated to a regular military structure. Its real leadership is unknown, but probably Russian.

During a recent meeting in Donetsk with a senior security official, my host paused to take a call. He listened impassively to a long report from a clearly shaken local commander, then hung up. Our Russian military minders are "screaming" at one of our artillery positions for responding to Ukrainian shelling, the official explained. "If we fire back, we get into trouble. If we don't, morale plummets," he remarked. Such complaints are sometimes accompanied by warnings that ammunition and supplies may be cut.

It should be easy for Moscow to control its far smaller clients. Russia arms, feeds, and funds the breakaway areas. Only two Donetsk leaders have even a modicum of independence, another member of the leadership told me recently. (Make that one now: Soon after our conversation the second of the two leaders was arrested.) "The rest of us," he said, "handle "technical issues." Separatist leaders obediently attend negotiations in the Minsk format, but they cannot even change the punctuation of any statements, he said.

Already in May 2014, Russia seems to have decided it would not incorporate eastern Ukraine into Russia militarily. Putin likely received convincing intelligence reports that incorporating the east would be much messier and more complicated than Crimea. "They ran out of ideas for us over a year ago," one leader constantly says.

Meanwhile, the Russians failed to organize a political or administrative structure, losing time in what looked like a permanent holding pattern. They treated us like "a suitcase without a handle," another leader remarked. "It's useless, but you can't bring yourself to throw it out."

During this time of constant improvisation in the Kremlin, some of the new local leaders were busy. Powerful criminal groups sprung up with both local political clout and serious firepower. A thriving cross border trade sprang up, with guns, drugs, consumer goods, scrap metal and coal crossing both the border with Russia and the line of separation between separatists zones and the rest of Ukraine.

Little of what is happening now is a surprise to the separatist leadership. Rank and file have been suspecting for months, if not longer, that Putin was preparing to dump them. A month or so ago I asked leaders in Donetsk whether such a scenario was possible. One answered with a long and circuitous speech that boiled down to: "Yes." Andrei Purgin, cautious and still very supportive of Russia, sidestepped slightly, saying: "This is a complex and slippery question." He did not rule it out, though.

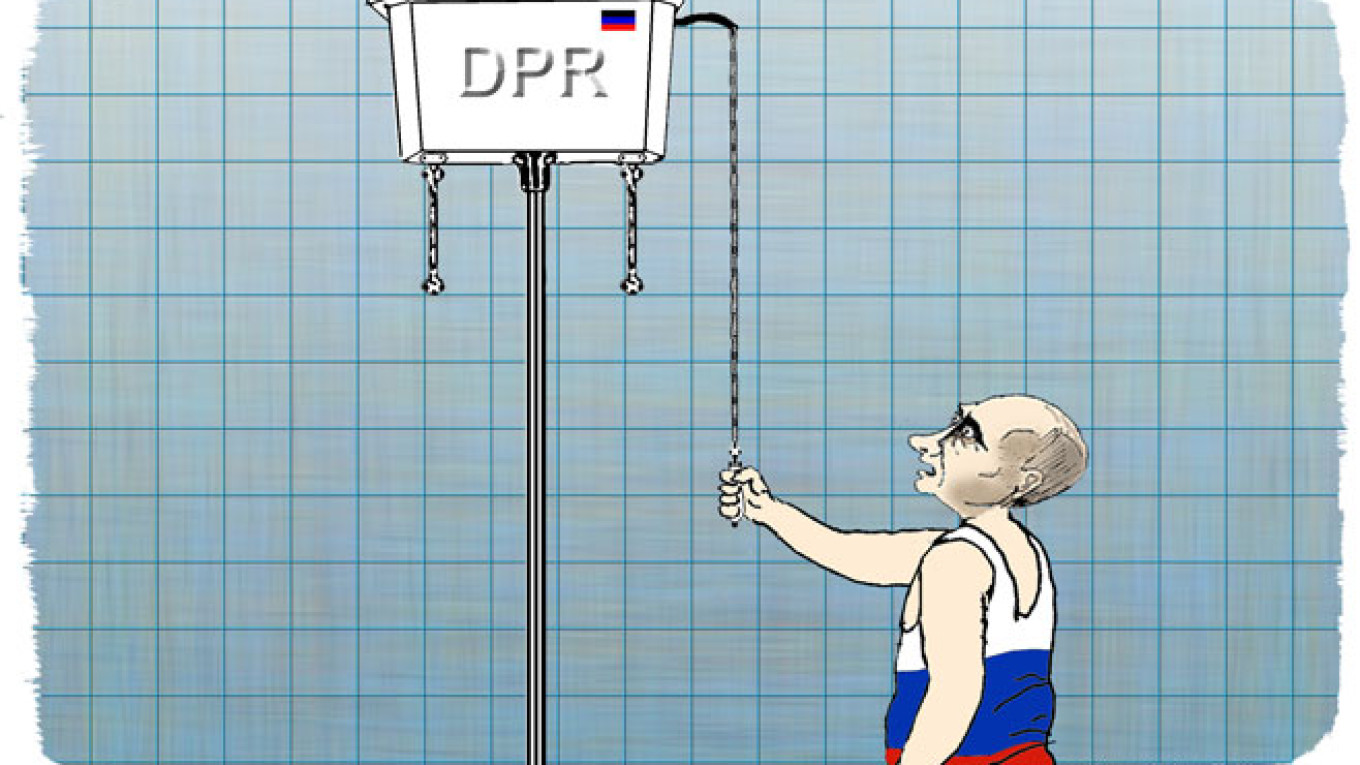

Another problem, one of the subtler analysts in the leadership remarked, is that for the past year hardliners and moderates in the Kremlin have not reached any consensus about what to do next. "At times the military aid tap would flow abundantly, and we felt something was going to happen," one recalled. "Then it dried up again, and we were told to implement the Minsk agreement. The towers of the Kremlin were fighting against each other," he said.

The political confusion and competition in Donetsk is thus a reflection of the struggle in Moscow, and it is not slowing down. When I asked which side Putin was on, the analyst demurred. In fact Putin might not be on either side. He may well be where he often is: in the middle, trying to work out which way to go. Military success in Syria may help him by pushing Ukraine off the headlines. But it will not solve the problem he created in eastern Ukraine — and perhaps in the long run at home.

Paul Quinn-Judge is senior adviser on Ukraine and Russia at International Crisis Group, the independent conflict-prevention organization.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.