Gianadda took hundreds of photographs of everything he saw in Moscow, from babushkas sweeping church floors, to the changing of the guard at Lenin’s Mausoleum, to construction workers sweating on the job and love affairs kindling after the festival shut down for the night. Officially, Gianadda was sent to the festival as a journalist, but he took the majority of his photographs out of sheer personal interest.

“Gianadda was an official correspondent for the Swiss French-language newspaper L’Illustre, and as a correspondent he had to attend the official events. As a young person, of course, he was interested not only in the official events. It was very interesting to see Russians, to see who they are, what they are,” said Olga Averyanova, a curator of the Pushkin Museum’s current exhibition of Gianadda’s photographs, entitled “Moscow. 1957.”

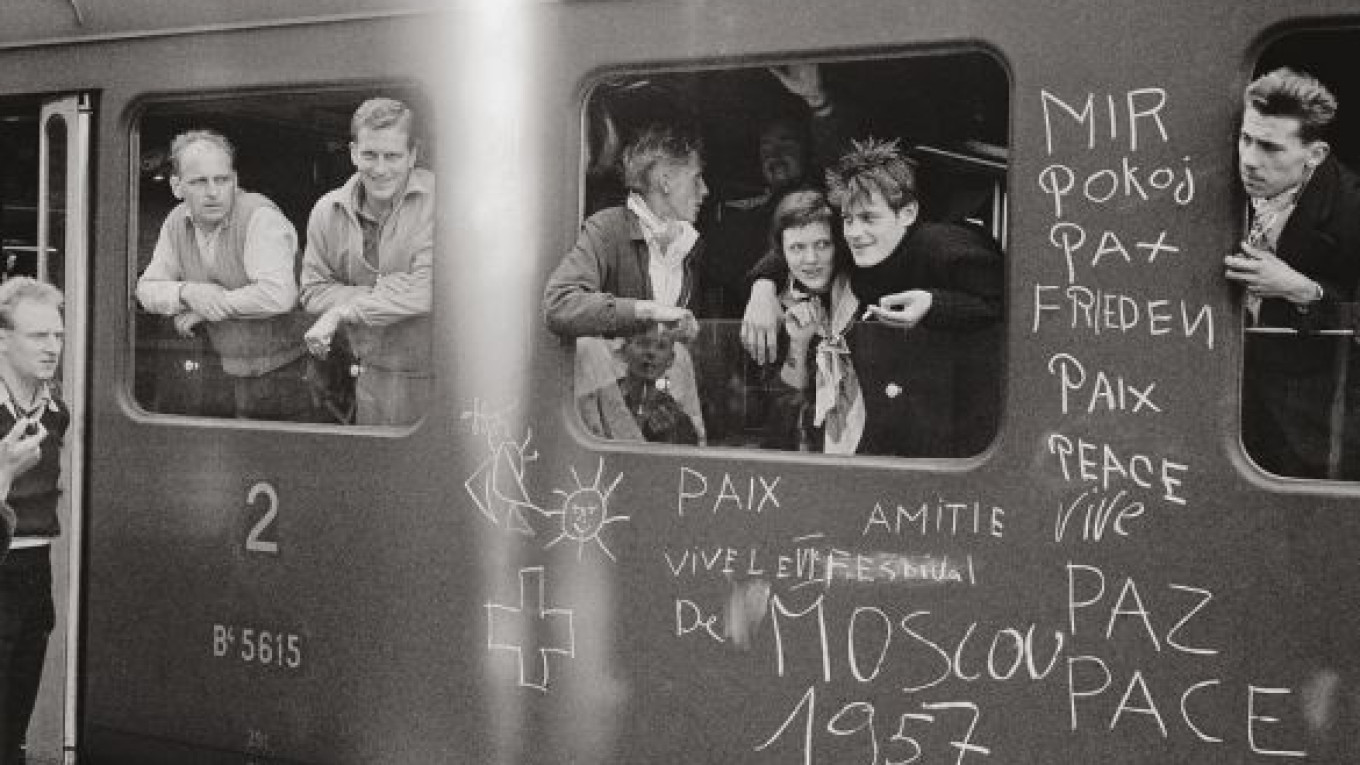

The youth festival opened June 28, 1957 and drew 34,000 guests from 131 countries in the name of peace and friendship. A political move that was part of Khrushchev’s reforms, the festival proved to be a revolutionary, myth-breaking meeting of cultures. Russians were initiated into Western culture’s jazz, jeans and new ways of thinking.

“I didn’t understand then that for the U.S.S.R. it opened up the world,” Gianadda said, in an interview with Moskovsky Komsomolets. “Only now has the meaning of what happened in 1957 been explained to me.”

Unfortunately for Gianadda, a photograph he took of the Hungarian Chairman of the Council of Ministers Janos Kadar receiving a pin at the Swiss Embassy was seen as Communist propaganda by his newspaper. The newspaper refused to print his photographs, and he bitterly left journalism for a career in business.

The photographs remained undeveloped and forgotten until their recent rediscovery. Gianadda himself saw many of them for the first time, Averyanova said.

The exhibition begins with photos of trains of foreigners arriving in Moscow and then covers a number of different themes from Russian women at work, activities on Red Square and scenes of everyday Russian life.

“It’s surprising that [even though Gianadda] was so young, the composition of the shots is very good. He creates a dialogue between the photographer and the composition,” Averyanova said.

As tourist images of Moscow landmarks fade into the background of Gianadda’s photos, many are strikingly candid. There are hugs, kisses, smiles, frowns and stares of confusion at Gianadda’s foreign camera. Only one man in the entire exhibit has the well-built, tanned image of Soviet poster art.

“I was very surprised that I was allowed to completely freely wander around Moscow and look in all the back streets without limitation,” Gianadda told the magazine Ekho Planety. “Before the trip I had been convinced of the exact opposite.”

Gianadda even telephoned the Soviet Olympic long-distance runner Vladimir Kutz and was invited into his home, where Kutz showed off his trophies to the young fan.

Gianadda went into construction and real estate after graduating from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in 1960. After his younger brother Pierre died in 1976, Gianadda started a philanthropic foundation in his brother's name that today operates a museum complex in Martigny, Switzerland. The undeveloped film of the Moscow pictures was discovered by a curator in the foundation’s library, and the curator persuaded Gianadda to exhibit the photographs.

Gianadda captures the contrast between Russian and foreign, between the poverty of the people and the richness of the Moscow landscape. The photos might seem critical in another photographer’s hands but he, as seen in photos where he smiles along with Russian friends, is an interested observer.

“He doesn’t have a critical perspective. He is kind and open, and people respond to him like that, too,” Averyanova said.

“Moscow. 1957” runs at the Museum of Private Collections at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts until March 14. 12 Ulitsa Volkhonka. Metro Kropotkinskaya. Tel. 697 7998, www.museum.ru/gmii.