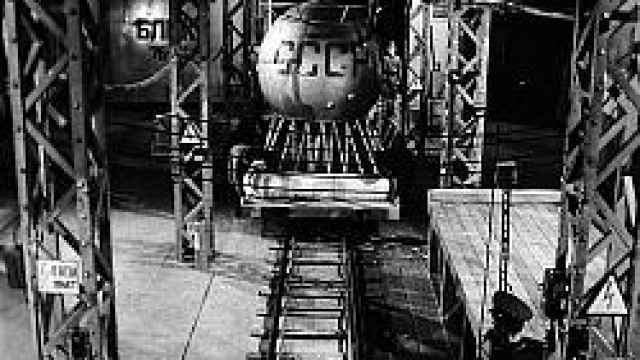

The reason for such classification problems are clear enough from the film's subject. Working around the idea that the Soviet Union developed a space program in the 1930s, a project that culminated in a 1938 rocket launch, Fedorchenko mixed a range of material into "First on the Moon," from actual period newsreels to episodes scrupulously shot in the style of that time. Weaving between them are contemporary scenes, shot in color, which provide a linking strand in the form of a documentary investigation into the fates of the program's participants. Screenings at Venice blurred the differences by bringing up the house lights before the film's closing credits -- which confirm that all roles were played by actors.

The result is stylish, sometimes very funny and ultimately affectionate toward its chosen subject. "The element of irony is very small, perhaps around 5 percent," Fedorchenko said in an interview this week. "The rest is something of an homage to the generation of our fathers or grandfathers, including their honesty, their genuine belief in an ideal."

Fedorchenko said that there was no single key to appreciating the film and that different viewers would react to it differently -- reaction to an early screening at the Star City space center outside Moscow was largely favorable, he said. But the director didn't endorse some of the terms that have been used to describe his work. "We didn't aim for mystification, but for a fantasy drama. Terms like 'postmodernism' and 'mockumentary' are not what we intended. Perhaps the genre is documentary fantasy," he said. Fedorchenko also seemed weary of questions from journalists referring to Viktor Pelevin's novel "Omon Ra," a comparable story that also debunked some Soviet space myths.

In many ways, the career of the Yekaterinburg director, now 39 years old, is just as unusual as his film. After graduating in 1988 with a degree in economics, he started work at a factory. Two years later he moved to the Sverdlovsk Film Studio, joining its documentary facility, at a time when the once-highly respected studio was passing through difficult times, with production virtually halted, salaries unpaid and electricity intermittently cut off. Only the appointment of a new general director and an invitation to become his assistant persuaded Fedorchenko to stay at the studio.

www.arthouse.ru Fedorchenko's film shows 1930s space technology and sinister medical experiments. | |

"We were state officials, but the state seemed to have no need for the studio. We fought for it like it was our own, but it wasn't," he said. Finally, by the late 1990s -- despite the financial crisis of 1998 -- the studio was more or less back on its feet. Even though Fedorchenko left his job at the organization later, in circumstances that he seemed reluctant to discuss in detail, the studio helped produce "First on the Moon." The director joked that almost half the studio's staff took part in the film, both behind the scenes and on camera.

Moving to the screenwriting faculty of Moscow's VGIK film institute in 2000, Fedorchenko turned to making documentaries. His first, "David" from 2002, took major prizes at European festivals; its story of a Jewish survivor of both Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Soviet Union attested to Fedorchenko's interest in the 1930s and 1940s. His second, "Children of the White Grave," followed a year later, coming close to home: It focused on members of the ethnic groups deported to Kazakhstan by Stalin, including Koreans, Chechens, Poles and Germans.

Fedorchenko put off his plans for more documentaries about the period when he read the script of "First on the Moon." Written by Alexander Gonorovsky and Ramil Yamaleyev, it had been in pre-production at Mosfilm in 1997 but had fallen victim to the following year's financial crisis. Its themes, embodied in the heroism of volunteers for a secret program who are finally discarded and destroyed by the system that had nurtured them, struck a powerful note for him, as did the possibilities and challenges of creating an exact replica of the documentary visual styles of the 1930s.

www.arthouse.ru | |

Less than a tenth of the final film is drawn from original archive material -- most notable are scenes of athletes parading on Red Square and extracts from Vasily Zhuravlyov's 1936 science-fiction feature "Cosmic Journey," about just such a moon expedition. All the rest of the black-and-white material was scrupulously created to match, a painstaking process that required designer Nikolai Pavlov and cinematographer Anatoly Lesnikov to find old cameras and film stock, sometimes shooting sequences at the rate of eight or 12 shots per second before developing them at the standard rate of 24. Developing facilities at places like VGIK turned out to be a close match, and extra grainy notes and scratches were added during post-production.

Even though such "fake" footage is silent, Fedorchenko still manages to develop the characters of his protagonists. Chief among those who pass the project's selection process are Ivan Kharlamov (Boris Vlasov), a heroic figure who becomes the final cosmonaut, the athlete Nadezhda Svetlaya (Viktoria Ilyinskaya) and the circus dwarf Victor Kotov (Andrei Osipov). We see parts of the material through the eyes of the program's only remaining survivor (Anatoly Otradnov in youth, Alexei Slavnin in old age); other present-day figures are linked to the experiment less directly. The depiction of their lives in old age -- one is shot from a hospital bed -- emphasizes the contrast with the idealism of youth.

But it's an idealism countered by a sense of the sinister, with a considerable part of the footage purportedly drawn from NKVD surveillance material; one episode demonstrates the potential of the security service's newly developed handheld hidden camera. Through such footage we catch glimpses of the private lives of the mission's participants. Most chilling are shots that show Svetlaya and others -- after the mission has been officially covered up -- gassed in their sleep.

Kharlamov's fate is the most enigmatic. The cosmonaut becomes a Zelig-style character whom the film follows in the aftermath of his flight -- from a presumed landing in Chile to a protracted return across the Pacific to his capture on the Mongolian border. After being incarcerated in a Siberian asylum, he escapes and appears to move through a range of identities over subsequent years. It's an intriguing conclusion, although some of the rhythm and direction of earlier parts is dissipated.

Generously funded with a budget of about $1 million, almost exclusively from state sources, Fedorchenko's film can hardly be faulted stylistically, whether it's on monumental scenes like the rocket's blast-off, or on closer, often comic moments like preliminary experiments with a dog and a monkey. Some episodes have an intriguingly unexplained character, like the appearance, in one preparatory scene, of a group of German officers -- almost impossible in the historical context, but somehow stressing the sheer randomness of fate and the way history comes to be documented. But the real strength of Fedorchenko's film lies in its uneasy balance: While there's much that will draw laughter from today's audiences, the more elegiac and human strands of "First on the Moon" are no less strong.

"First on the Moon" (Perviye na Lune) is playing in Russian at Fitil and Pyat Zvyozd-Novokuznetskaya.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.