The black-and-white footage all came from the archive of the St. Petersburg Studio of Documentary Films, which, surprisingly, has only 3 1/2 hours of material from the period. "Blockade" is made up of fragments, some quite lengthy, that show the gradual transformation of Leningrad over the 900-day siege, in which over half a million city residents died, most of them from starvation.

Loznitsa never considered adding commentary to the film, he said in a recent interview at Dom Kino. "If I put in a voiceover, I offer my view, and that means I exclude the possibility of the viewer having his own view," the director said. "He has either to agree with me or not agree with me."

The soundtrack uses material taken from the archive as well as contemporary recordings of crowds, such as one from a market in Minsk. "When you completely take away any words and add ordinary sounds to the footage, doing so convincingly, it suddenly opens up in a different way," Loznitsa said.

The film had its Western European premiere at the Rotterdam Film Festival in February, and it was shown at the New York Underground Film Festival earlier this month. Last week, it won a White Elephant, a prize awarded by Russian critics. It is also nominated for best documentary in the Nika competition, whose award ceremony is today.

The first scenes show German prisoners being paraded down a central street, with passersby hurrying past or stopping to stare. One woman runs alongside the convoy and suddenly spits at the soldiers, most of whom have limbs in slings or walk with crutches.

As the fighting draws closer, people run for shelter during air raids, hastily draw blackout curtains and fight fires that rip through buildings -- scenes that echo what was going on in London or Dresden at the time.

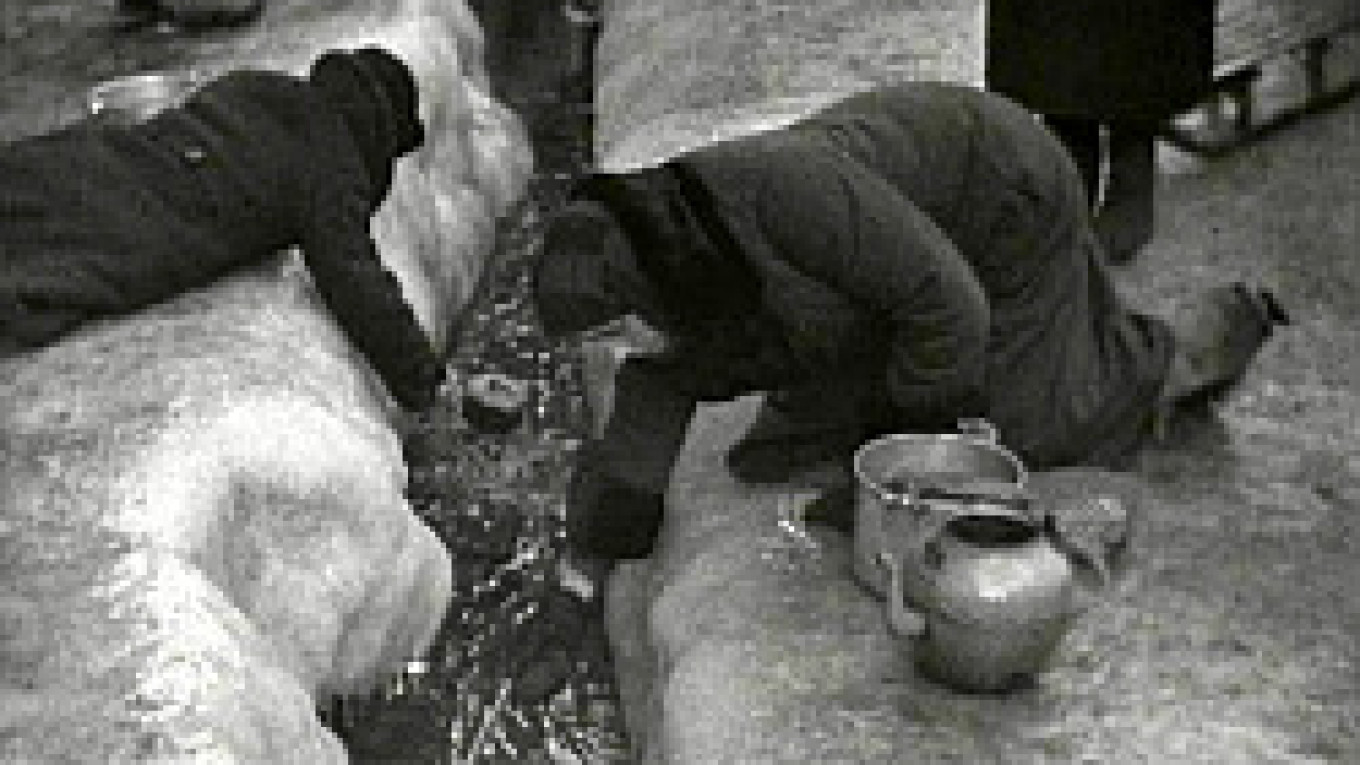

Slowly, though, the city loses power and petrol, trolley bus wires drape the roads and trucks are abandoned. People break up the seats in a stadium for firewood. A handwritten notice lists household goods, from a bed to a guitar. "I will sell or exchange them for food or papirosy cigarettes," it explains.

"I tried to structure the film around the onset of horror," Loznitsa said. "Death advances, and life falls away. That happens gradually and unnoticeably for us; we gradually immerse ourselves in the nightmare of a completely absurd existence."

At its worst, the besieged city is full of bundled figures pulling sledges, some loaded with shrouded corpses. The footage of the siege ends with a scene of bodies being prodded into place in a mass grave.

Despite a lack of outlets for documentaries in Russia, the film has been warmly received, Loznitsa said. After a recent showing for siege survivors in St. Petersburg, an elderly lady called the studio asking to meet the director, he recalled. When the receptionist asked her why, she explained, "'I want to give the boy a hug,'" he said.

That's not to say the film sentimentalizes the period. After the scenes of Victory Day fireworks, the film cuts to a huge crowd in a square, jumping up to see what is happening in the center, where a group of men are being hung from a gallows.

This footage, shown at the end of the film, was shot in 1946 and comes from a documentary called "The People's Verdict," Loznitsa said. It shows German prisoners of war, a detail that is secondary in the director's view. "Only 60 years ago, we gathered on the street and watched other people being hanged," he commented. "On the one hand, you can understand people, since they lived through something that -- I don't know -- reconciled them to such a fact."

On the other hand, though, the scene is "impossible to understand" for people today, he added.

Originally from Kiev, Loznitsa studied at the VGIK film institute in Moscow and moved to work in St. Petersburg in 2000. He still travels to the city regularly from Lubeck, Germany, where his family emigrated to four years ago.

In his documentaries, the director never uses voiceovers or sounds recorded on location. His 2003 film "Landscape" shows villagers waiting at a bus stop with a soundtrack of snatches of their conversations. "I have films where there are words, but the words are like sound-music," he said. "Of course, they have meaning, among other things."

Inspired by working with archival material, Loznitsa now plans to make a film that will use rose-tinted newsreel footage to build up a portrait of an imaginary town. It will be called "Presentation," after a poem by Joseph Brodsky that satirizes the Soviet way of life.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.