Consider, by way of contrast, the fate of a Russian convict described in Edward Kuznetsov's 1973 "Prison Diaries," upon whose forehead prison surgeons operated three times to remove a political tattoo:

"The first time they cut out a strip of skin with a tattoo that said 'Khrushchev's Slave.' The skin was then roughly stitched up. After he was released, he tattooed 'Slave of the USSR' on his forehead. Again, he was forcibly operated on to remove it. [The] third time, he covered his whole forehead with 'Slave of the CPSU' [Communist Party of the Soviet Union]. This tattoo was cut out and now, after three operations, the skin is so tightly stretched across his forehead that he can no longer close his eyes."

Russian criminal tattoos have, in some small but significant way, begun to infiltrate and influence the Western creative class' ideas of Russia at its most outre. In recent years, they have been depicted in David Cronenberg's film "Eastern Promises" and in Martin Amis' novel of the Great Terror, "House of Meetings."

That anyone outside Russia should know anything about the phenomenon is due in no small part to the efforts of Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell, the founders of the London-based publishing and design company, FUEL, which has recently released the third volume of its popular "Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia."

In a recent e-mail exchange from London, Murray described how his and Sorrel's desire to bring the dark and splenetic, anti-authoritarian aesthetic of the Soviet underworld to English-speaking audiences took shape.

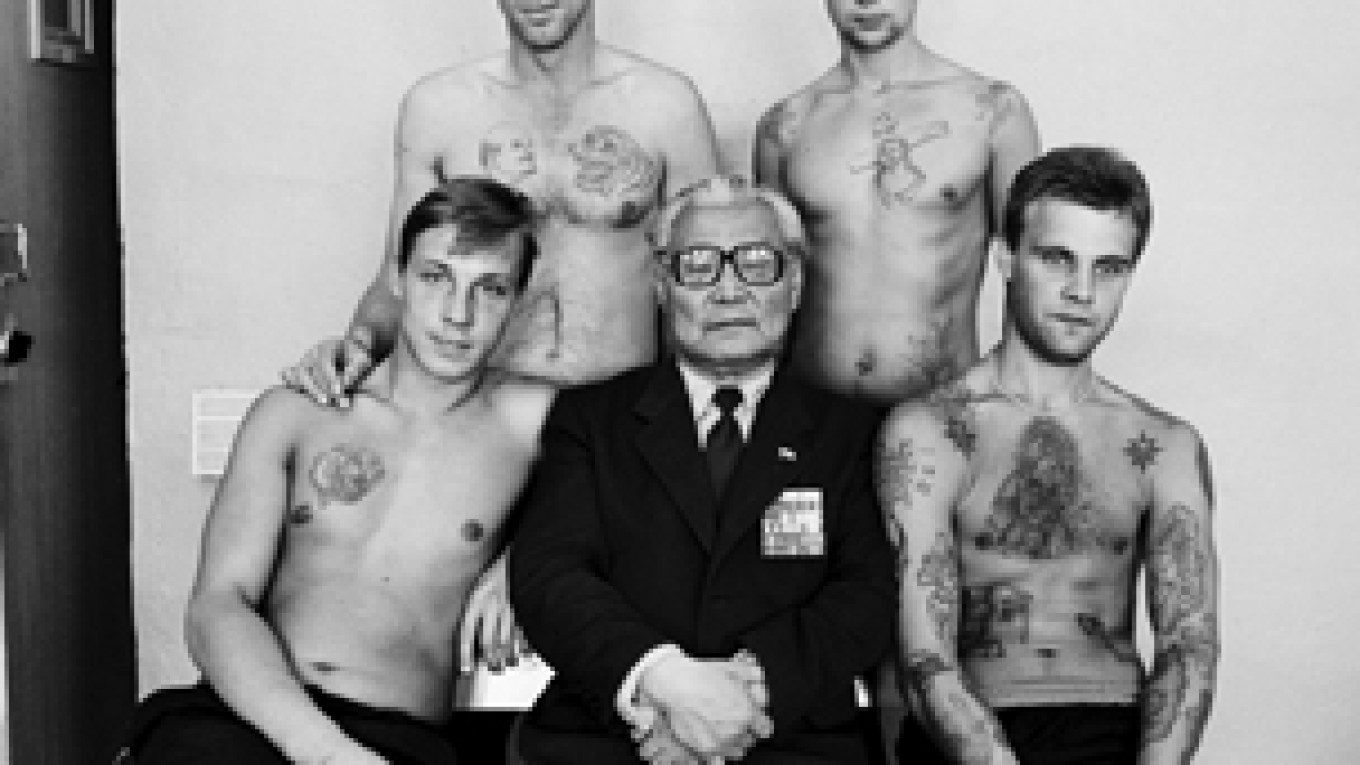

Sergei Vasilyev / Fuel Publications 2008

| |

"Each issue was themed around four letter words, and USSR seemed an interesting play on this — particularly at a time when Yeltsin had just declared, 'Everything, everywhere, is for sale,'" he added.

Murray and Sorrel had an acquaintance working for a Russian publisher who showed them drawings by Danzig Baldayev, a guard at St. Petersburg's Kresty Prison who was also a talented amateur anthropologist and folklorist. Baldayev had made detailed copies of the tattoos of hundreds of prisoners he had encountered.

The tattoos Baldayev depicted were a language in themselves, comprised of a rich array of symbols and illustrations that denoted a prisoner's crimes and political allegiances, as well as his or her rank in the prison hierarchy. Prisoners typically applied them to each other — not always with consent — using inks improvised from soot, sugar, ashes and urine.

The tradition derives from the practice of tsarist prison authorities, who branded the faces of hard labor convicts, identifying them as criminals for life.

Fuel Publications 2008

| |

A typical anti-communist tattoo in the most recent volume of the series depicts Lenin as a horned, hairy demon - the manner in which Russian convicts typically depicted "Jews" - being crucified and roasted over a burning copy of Marx's "Capital" by two angels. The text below reads, "God's trial for the leader of the world's proletariat."

"We had never seen anything quite like them," Murray says. "The fact that the same hand had made all these drawings made the subject something that could be grasped, measured and catalogued. They were very interesting as objects in themselves, made with an ink pen on thick art paper with Baldayev's 'official' stamp and initials in each corner."

In addition to Baldayev's drawings, Murray and Sorrel were shown black-and-white photographs of the tattoos taken by Sergei Vasilyev, which, Murray says, became an important -accompaniment to Baldayev's illustrations because they confirmed their authenticity.

When Murray and Sorrel expressed interest in turning the drawings and photos into a book, Baldayev and Vasilyev wanted to produce a coffee table book. However, the designers had a more ambitious aesthetic approach in mind.

Danzig Baldayev / Fuel Publications 2008

| |

"We wanted people to be able to pick them up without being frightened off by the covers, so we chose pastel colors, which also felt quite Russian to us. The books appear quite beautiful as objects, which is a deliberate contrast to the often shocking and dark content," he added.

In addition to being attractive art objects, the books exhibit a scholarly quality. While Baldayev was unable to pursue the education he desired because his father had been declared an "enemy of the people," he was nevertheless a formidable autodidact and pursued his subject with scholarly rigour.

Although Baldayev died shortly after the publication of the first "Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia," Murray and Sorrel have aimed to preserve the serious tone of his work by inviting various experts to contribute to the books.

Danzig Baldayev / Fuel Publications 2008

| |

Murray and Sorrel continue to develop books on other aspects of Russian visual culture.

"As Russia [particularly Moscow] has changed over the last 15 years, it has interested us that elements of that society we glimpsed when we first visited in 1992 have started to disappear. As the general Russian culture becomes more 'Westernized,' more transient social traditions fall by the wayside. We aim to document them," Murray said.

FUEL has recently published "Home-Made" by Vladimir Archipov, which documents tools and other items made by ordinary Russians because of the lack of consumer goods in the Soviet Union, and "Notes From Russia" by Alexei Plutser-Sarno, which is a portrait of the Russian street told through public notices.

All of FUEL’s Russia books address the layers of individuality and transgression that manifested themselves visually, by admirable or dubious means, throughout the Soviet era. Much of what they have documented shows up the frivolity of off-the-shelf modes of expression cultivated in the West during the same period.

“I often remark on how tattoos today are merely based on style, as worn by footballers and pop stars,” says Murray. “We believe that the interest in the Russian criminal tattoos is because they actually have meaning.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.