After losing the final game of the Ice Hockey World Championships, Russia's national team left the ice without waiting to hear the Canadian national anthem performed in honor of the winning team. But if the Canadians had left while the Russian national anthem was playing, Russia's state-controlled television and press would have complained for two weeks straight, saying, "How could they dare disrespect us like that?"

Russia has a strange understanding of respect: that it works in only one direction.

For example, I have no qualms about parking my car in the middle of the sidewalk, making it impossible for other parked cars to leave, and also covering my license plate number with a patriotic St. George ribbon to avoid a parking fine. But that does not prevent me from losing my temper if someone else does exactly the same thing to me.

Taken together, these countless episodes of mutual disrespect add up to one giant wave of negativity that affects everything from the "vibe" in the nearest coffee shop to Russia's foreign policy. The behavior of Russia's national hockey team — and professional athletes in general — is connected with foreign policy. What's more, international athletics are often the only outlet through which two countries locked in political rivalry can send each other friendly signals.

But Russians consider such friendly signals a sign of weakness. The same goes for anyone who actually parks in a paid parking area without masking over his license plate. Anyone who does that is viewed as a simpleton unworthy of respect. Russia has no place for public displays of gentleness or kindness — only for strength and gruffness.

In this system, strength is more important than right. The annexation of Crimea is only one proof of this, and in the end it is very difficult to explain that annexation in terms of international law to people who are often unaware not only of their constitutional rights, but also of their basic rights as employees.

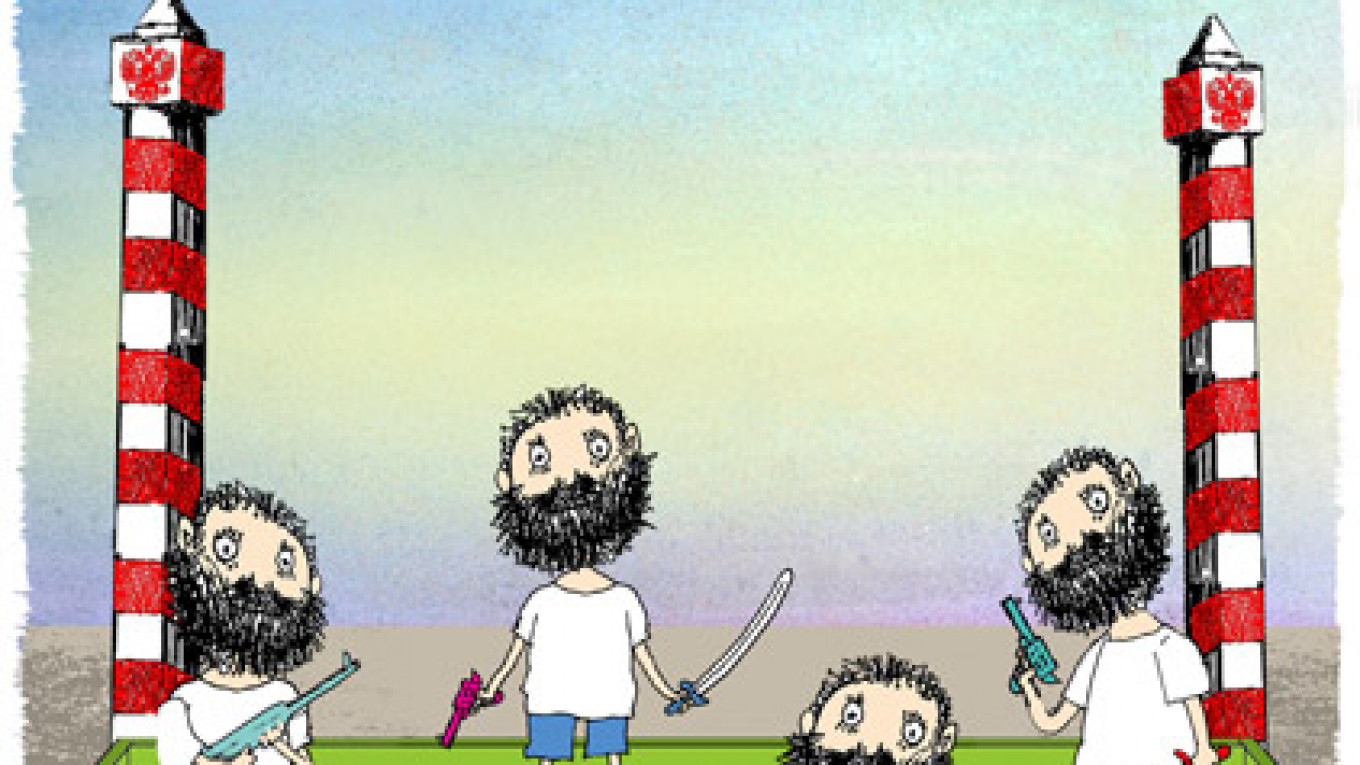

And then we have the country's president in the company of bearded members of the Night Wolves motorcycle club, a group that once positioned itself as inveterate enemies of the state. Police records from the early 1990s show that the Night Wolves is far from a harmless club of wealthy men under 50 who bought themselves fancy U.S. motorcycles: they have outright criminal episodes in their past.

But such is Russia's image today: criminal types riding motorcycles team up with the president to speak out in support of so-called "conservative values."

And it so happens that the head of one of the North Caucasus republics also has a beard and his entourage is not unlike the Night Wolves biker club in that it is full of people who not only have problems with the law, but even fought an armed struggle against the Russian army.

More than a few people occupying senior administrative posts in Grozny were on Moscow's list of wanted men in the past. But federal police never received and never will receive permission to snap handcuffs on their wrists because delinquent boys who grew up as men in trouble with the law are the main heroes in today's Russia: they can do whatever they please — even openly and publicly disregard the law.

This is the reason for the public's dissatisfaction, and not merely the fact that a middle-aged and married Chechen police chief recently took a 17-year-old girl as his second wife with a dozen news cameras looking on.

Polygamy in Chechnya, as well as early marriage everywhere in Russia, is not news. The real problem is not ethnography, but the fact that the protagonist in this story is an employee of the federal police.

And if it were not enough that the bigamous marriage violating Russian law was held before television cameras, it turned out the registrar who made it official was actually a journalist invited especially to play that role in the scandalous event.

Even if it turns out that the young bride was not forced into the marriage, that the couple's relationship was somehow not bigamous and that the reporter posing as a registrar actually had the right to perform the service, the whole episode does nothing to improve the reputation of the Chechen police.

And yet Moscow will not impose any disciplinary measures or changes to the police department there because it happened in a republic controlled by one of President Vladimir Putin's personal bearded favorites.

These bearded favorites of the president certainly do look like tough and unforgiving fellows, and God forbid anyone would refuse to get out of their way quickly enough.

Strength is their main principle, and strength is how they force others to respect them — while totally disregarding the rights of everyone else. They are really the heroes of the day, the ideal, the role model to emulate, the very image of charming provincial macho. Every Russian would like to be the same. These are also men who would never consent to hang around on the ice waiting for the Canadian national anthem to play.

As a skilled populist, Putin obviously exploits such characters for his own benefit: now every office grunt who parks his Toyota across the sidewalk can imagine himself a little Ramzan Kadyrov or an aspiring Night Wolves biker.

But when that same grunt leaves the office at 6:30 p.m. to go home and watch television to see how Russia's ice hockey team thumbs its nose at the Canadians or how their president scores eight glorious goals in a demonstration hockey game, he often finds that somebody else has double-parked behind him.

And to get his car out, he must spend half an hour and half a dozen calls screaming at various people at the top of his voice. At that moment, he has no need of Ramzan Kadyrov or the Night Wolves, but finds himself wishing that at least the police would do their job.

But these presidential bearded boys are apparently just what's needed considering that something is seriously wrong with the police — and with all public institutions in Russia. It turns out that, after 15 years of Russian authoritarianism, the institutions that existed before have reached such a deplorable state that the president himself has little choice but to befriend incorrigible street thugs.

That cult of ruffians and punks masks a gaping institutional void. It is a game of force that disguises weakness — a real and horrifying weakness, one that makes a leader's knees tremble out of fear that everyone else will soon discover it as well.

For now it is just a game, but in a country that honors the "law of the pack," the one who betrays the least sign of weakness finds himself in a singularly unenviable position.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.