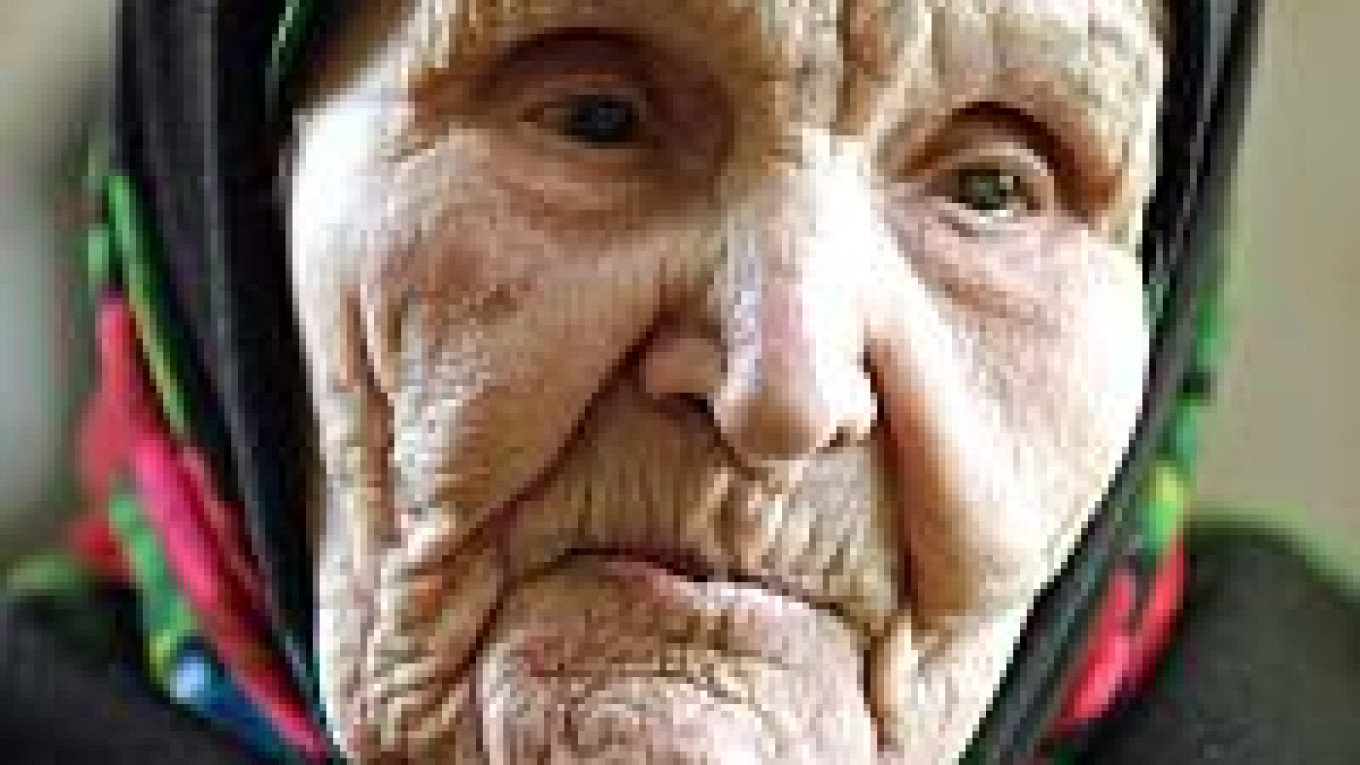

"I'll drink to my own health with pleasure," said Hanna Barysevich, who turned 116 on Wednesday. "I'm tired of living already, but God still hasn't collected me," she added with a smile.

Barysevich was born on May 5, 1888, in Buda, 60 kilometers east of Minsk, according to her passport. Her parents were poor, landless peasants. "From my early childhood I didn't know anything but physical labor," said Barysevich, who never learned to read or write.

After retiring from farm work, she moved to a house near Minsk that she shares with her daughter Nina, 78.

The worst period of her life was the reign of dictator Josef Stalin: Her husband, Ippolit, was declared an "enemy of the people" for allegedly harming the collective farm, arrested and taken to Siberia. He was never heard from again. She raised her three children on her own, including throughout World War II. "A lot of men courted me, but I preferred to live on my own," she said.

Today, Barysevich moves with difficulty but unaided. She complains of occasional headaches and worsening vision "but nothing else bothers me."

She attributes her longevity to genes: Her paternal grandmother was 113 when she died. As to diet, Barysevich prefers simple village food: homemade sausages, pork fat, milk and bread.

Nina said her mother has a good appetite and very strong nerves.

"Throughout my long life, I understood that it isn't worth it to get upset and take everything too close to the heart," Barysevich said.

For her birthday, she hoped for the raise in her monthly pension, equal to $50, and a chance to go to for confession.

Barysevich may well be the oldest woman in Belarus. Russia claims to have two women who are 122 years old. Both live in Chechnya and were put on record during the 2001 national census.

Last month, the Guinness Book of Records recognized a 114-year-old Puerto Rican as the world's oldest living woman. Barysevich said she had never thought of applying for the distinction.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.