As 300 angry voices drowned out Gennady Tokanov’s pleas, he retreated into a nearby police van to address the crowd from the loudspeaker inside.

“Don’t worry,” the deputy head of Moscow’s Akademicheskiy district said. “Your homes will not be demolished unless you approve of it.” His improvised speech, however, failed to calm the assembled crowd.

The meeting between municipal representatives and the district’s anxious residents whose apartments are slated for demolition was turning sour. An audacious renovation program which could see some 8,000 five-story buildings across the city reduced to rubble had many in the crowd worried for the future of their homes.

“This is violating the Constitution!” meeting participants shouted at Tokanov. “You’re disrespecting our property rights!”

Dozens of similar confrontations took place across Moscow on April 19. Many looked like the Akademicheskiy meeting, with hundreds of concerned homeowners mobbing local officials, anxious to learn the fate of their homes.

Moscow’s Mayor Sergei Sobyanin unexpectedly announced the program in February as an effort to upgrade rickety, five-story Khrushchevki. The pre-fab buildings, which were named after the 1950s Soviet leader, were only supposed to last 50 years.

Many had become dangerous to live in, Sobyanin said, and investing in renovations just didn't make sense.

But it soon became clear that the scale of the program was much more ambitious. Not only would the urban renewal program include all five-story buildings, authorities revealed, it could see whole districts torn down, regardless of their age or height.

Ahead of presidential and mayoral elections next year — and with core details of the program still to be made public — the plans have agitated thousands of Muscovites, including those who might otherwise abstain from politics.

Before and after

Muscovites are no strangers to urban development. In 1999, then Moscow Mayor Yury Luzhkov pledged to tear down 500 outdated Khrushchevki within 10 years. Most were in poor condition. Some residents feared for their safety.

Eighteen years on, the former mayor’s program is still not finished (68 buildings have still to be demolished). But Luzhkov’s plan never sparked criticism. The fact it wasn’t implemented more quickly was the only point of contention.

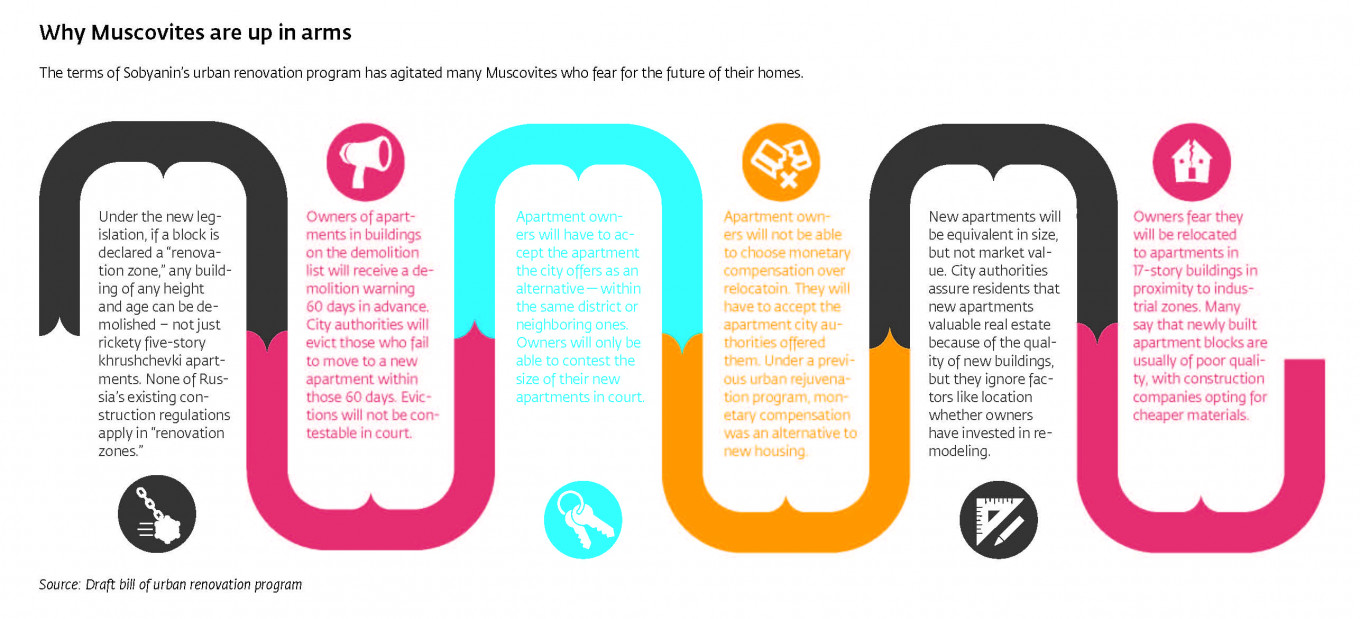

Owners of apartments in buildings eligible for demolition were warned a year in advance. They were offered three alternatives in the same district, equivalent in market value. They could opt for a payout instead. Improved construction standards meant the new apartments tended to be larger and of a higher quality than Khrushchevki.

The terms of the new program are much worse by comparison, explains Margarita Shefer, an activist in the Akademicheskiy district, during an impromptu courtyard meeting.

“If you don’t like the apartment they offer you, they’ll get a court order and evict you," she tells a crowd of frowning pensioners. “You’ll be warned 60 days in advance and not given alternatives to choose from.”

“They’re not offering property of the same market value. They’re offering property — in your district or a neighboring district — of the same size,” she continued. “This will be the only thing you’ll be able to contest in court – square footage.”

The bill that passed its first reading in parliament on April 20 includes more than just dubious apartment exchange protocol. The legislation allows Moscow authorities to declare whole blocks of buildings “renovation zones,” where existing construction standards and regulations would not apply.

The bill will make it possible for any piece of real estate to be demolished or built within a renovation zone, Pyotr Ivanov, a sociologist studying urbanism, wrote in a recent column.

“Talk of five-story buildings, Khrushchevki and outdated housing is just a pretext,” he writes.

Ivanov says the program is designed to benefit real estate developers. Russia’s construction industry has been stagnating since the 2014 economic crisis and real estate sales have plummeted.

The renovation bill offers relaxed regulations for construction companies. More importantly, it outlines giving residents new apartments that would be paid for from the city budget.

“Large developers not only get simplified real estate regulations but also a major buyer of real estate that would boost the demand for economy class housing,” Ivanov writes.

Several large construction companies have already expressed interest in the program. Some, according to news reports, are dropping existing projects to free resources for the lucrative renovation program.

Russian banks are also concerned about the redevelopment program — and the impact it will have on the mortgage market. If replacement apartments are less valuable than the aging apartments slated for demolition, banks will lose out if they reclaim property.

According to a report by the Kommersant newspaper, several large banks are proposing amendments to the bill that will ensure new apartments are equivalent in market value. This would benefit both banks and mortgage holders.

Cons outweigh pros

For ordinary Muscovites — whether they want new apartments or not — the plan is unpopular.

“I went out on a limb and remodeled my apartment,” says Olga, a Muscovite in her 30s who owns a flat in the Akademichesky district. “And now they want me to go back to square one, throw all this away and start afresh in a new, empty apartment.”

Others don’t want to give up their views, proximity to the metro, quiet neighborhoods, or nearby parks. “Why do I have to throw the dice and risk giving all of this up?” says Tatyana who lives in the same district.

Neither woman knows whether their buildings will be demolished because definitive lists have not been made available yet. But the head of the Akademichesky municipality, Elvira Shigabetdinova, told the district’s residents that every four and five-story building in Moscow is on the preliminary demolition list.

When residents of dilapidated buildings in the area ask Shigabetdinova when they will finally get new apartments — where floors are not rotting and pipes are not leaking — she frowns. “Sorry, your building probably won’t be torn down after all,” she says. “The land slot is too small for new construction. It’s just not interesting for developers.”

Some residents of aging Khrushchevki who want new apartments worry their replacements won’t be better. Economy-class buildings that are being put together now have lower ceilings, thinner walls and are usually made of cheaper materials.

“Moscow officials promise us better apartments,” says Shefer. “But the bill just says ‘equivalent [in size].’ If these promises are true, we want them in writing.”

The good fight

In the meantime, residents of five-story buildings are organizing. Many are sending letters to President Putin, Mayor Sobyanin and the State Duma. Neighborhoods gather in their courtyards to discuss the future of their homes and how they can work to save them.

“We realized we had to join forces with other buildings in our block to be heard,” says Vladimir, a resident of the Akademichesky district who leads an activist group in his building. “A whole block of buildings is a force to be reckoned with.”

Moscow authorities have been caught off guard by the pushback and hope it will be short lived. Anastasia Rakova, deputy mayor in charge of political issues, reportedly said during a recent city hall meeting that it was important to “avoid scandal” when the demolition lists are revealed.

“By late July the renovation topic should die down; people should focus on who's moving where,” she was quoted as saying in news reports.

State media have launched a media campaign to promote the program. The channels are airing segments about how happy Muscovites are about the prospect of moving from their buildings to better apartments.

Russia’s state-run VTsIOM pollster released a poll last month stating that 80 percent of Muscovites support the program. Those opposed to the program are frustrated that only 600 — of a possible 1.6 million — impacted Muscovites were polled.

Residents of some five-story buildings told The Moscow Times they received calls from their municipalities warning of “crazy activists” attempting to sabotage the program.

But Muscovites are skeptical. And some who say there were never interested in politics are becoming frustrated by the new legislation — and the authorities implementing it.

“I could have never imagined that something like this was possible until I started reading the bill,” says Olga. “This opened my eyes to how much corruption and lawlessness there is. I am never voting for [the ruling politicians] again.”

The reaction to the program is anything but unexpected, says political analyst Yekaterina Schulmann: for Russians, real estate is sacred.

“It's their home, something they want to pass on to their children, something they associate with their family,” Schulmann told The Moscow Times. “Messing with this is far from smart.”

This pushback is just the beginning, Schulmann adds. Ahead 2018 elections – both mayoral and presidential – authorities would have to cave and start bargaining. And starting from May 15, Muscovites will be asked to vote on whether they would want buildings they live in to be excluded from preliminary demolition lists that are supposed to be released on May 10.

“Making decisions without conferring with the people is not possible anymore,” Schulmann says.

Authorities are already making concessions. Mayor Sobyanin promised Muscovites April 27 he would amend the bill to guarantee new apartments in the same district. President Putin threatened not to sign the bill if it violates people's rights.

But Muscovites are wary. “I don’t trust statements,” says Alexei who lives in the Akademichesky district. “I trust laws.”.

“Right now authorities are lobbying for a law that violates my constitutional property rights," he said. "If they amend it, we can talk about trust.”