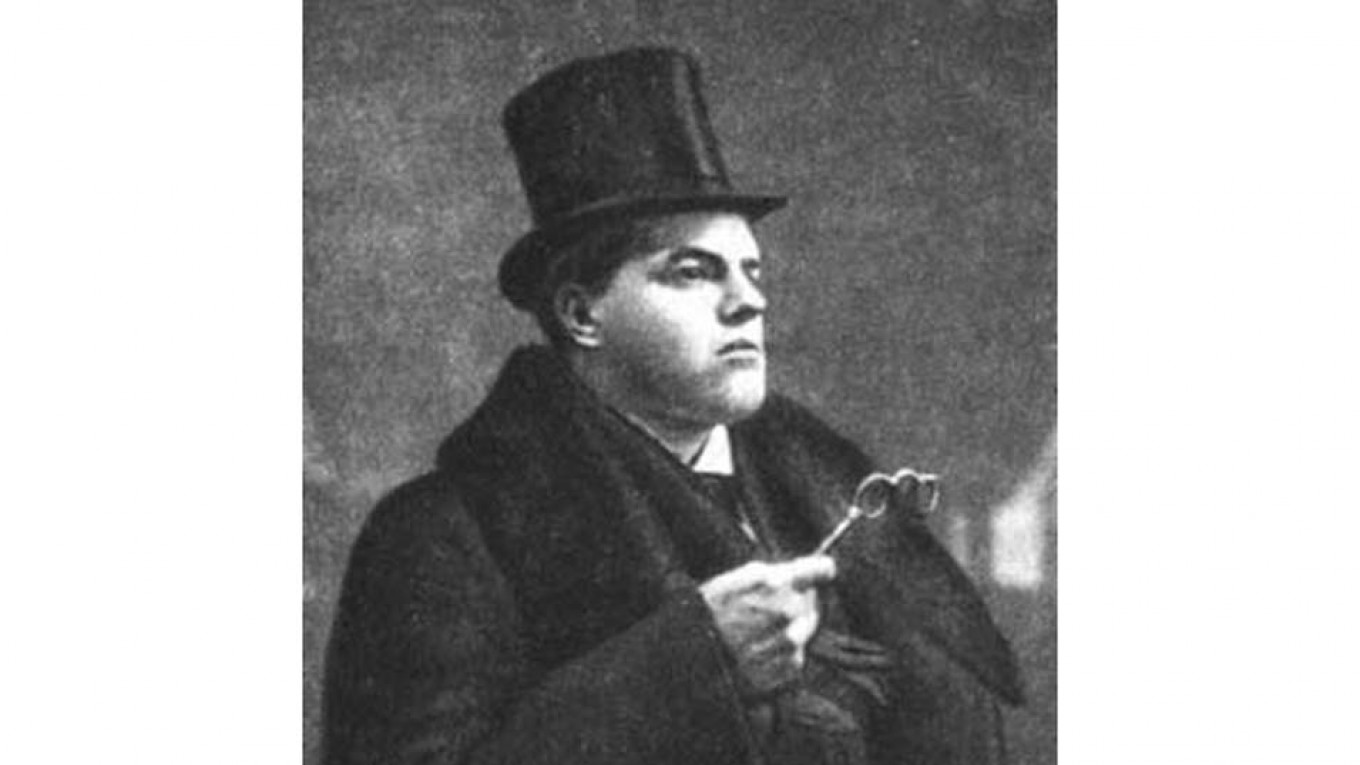

Even if you don’t know the avant-garde poet and artist David Burliuk, you’d probably recognize his image instantly: a stocky man in a frock coat and top hat, with a monocle in one eye and an abstract design painted on his face. He was one of Russia’s most prolific and versatile cultural figures. Called the “father of Russian futurism,” as a painter he worked in virtually every style of the 20th century — realism, impressionism, neo-impressionism, primitivism, fauvism, cubism, and futurism. He was most famous for his paintings but considered himself a poet. He was not as great a painter as his colleague and friend Mikhail Larionov or as great a poet as his other close friend Vladimir Mayakovsky, but he was the incomparable and indispensable leader of all Russian avant-garde artists and poets. He was deeply serious about his art and poetry, and yet he remained incorrigibly playful throughout his life, legendary for copying his own works and misdating them to order, one presumes, confuse art historians and scholars — which he did quite successfully.

And finally, while most Russians know who he was, almost no one has seen more than a canvas or two of his work.

But after more than a century, Moscow’s Museum of Russian Impressionism is hosting a grand retrospective of his paintings, poetry and self-published books. The show captures the mercurial nature of the artist. It is a serious, scholarly show presented with a bit of playfulness – as befits David Burliuk.

An artist’s path

Burliuk was born in 1882 in the village of Semirotovka, Ukraine in a large and artistic family. A childhood accident left him without an eye, which accounts for the monocle and, some scholars say, some peculiarities of his painting.

After studying art in Kazan and Odessa, he continued his education abroad, first at the Munich Royal Academy of Arts (1902-1903), and then at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (1904). He was influenced by his early experience with plein air painting — impressionistic sketches and experiments with surface textures that became one of his signature techniques: thick, richly painting surfaces that were almost architectural.

He was, from the beginning, a larger-than-life character. His early works, painted with “savage technique” were said to have “shocked the public.” One of his professors in Munich called him a “wonderful wild steppe horse.”

Back in Russia, Buliuk became one of the greatest proponents of French impressionism and neo-impressionism, and then, after a second trip in 1912, French cubism and Italian futurism. Burliuk was a poet, a creator of hand-made books, and traveling lecturer and reader of poetry. In 1910 he founded the futurist literary group Hylaea — the Greek name for the ancient Sythian lands that became Ukraine — that included Vasily Kamensky and Velimir Khlebnikov and was later joined by Aleksei Kruchenykh and Vladimir Mayakovsky. In 1912 he was co-author of the famous manifesto “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste.”

As a painter, he became friends with the great avant-garde artists Mikhail Larionov and Vasily Kandinsky, and was a member several groups, most prominently the Jack of Diamonds. He studied art for a year in Moscow before being expelled from the academy, and then traveled around the country with Mayakovsky and Kamensky, giving art shows and conducting performances — standing under suspended pianos and cavorting about the stage drinking tea and reciting poetry. Mayakovsky later wrote of Burliuk: “He was a great friend. My true teacher. Burliuk made me a poet. He read me the French and Germans. Shoved books at me. Walked and talked without pause. Didn’t let go for a second. Gave me 50 kopeks a day. So I wouldn't be too hungry to write.”

After a long “farewell tour” around Siberia and the Far East, in 1920 Burliuk and his wife Marusya went to Japan for about 18 months and then on to emigration in the United States, where they lived for the rest of their lives. Burliuk’s dream of becoming “the father of American futurism” was not realized, but he was a prolific painter, although now of smaller-scale works. He and Marusya produced a journal called “Color & Rhyme” and Burliuk painted copies of earlier works and made mischief with dates.

He was allowed to visit the Soviet Union twice, in 1956 and 1965, but as a poet, not painter. In 1967 he died on Long Island and was posthumously inducted to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

One path, three stages and a fourth profession

Burliuk’s works at the Russian Museum of Impressionism are exhibited in a roughly chronological progression in three main halls. The first hall displays his earliest paintings, done in an impressionistic style — which Burliuk called “the only path to find innovation in painting” — but with Burliuk’s trademark thickly textured surfaces (which you can examine through magnifying glasses placed in front of some of the works). “Apple Trees in Bloom” (1900) and “Summer in the Park” (1900-1910) almost burst off the canvas, in contrast to his touching “Portrait of My Mother” (1906) and the masterful blue “Oxen” (1908).

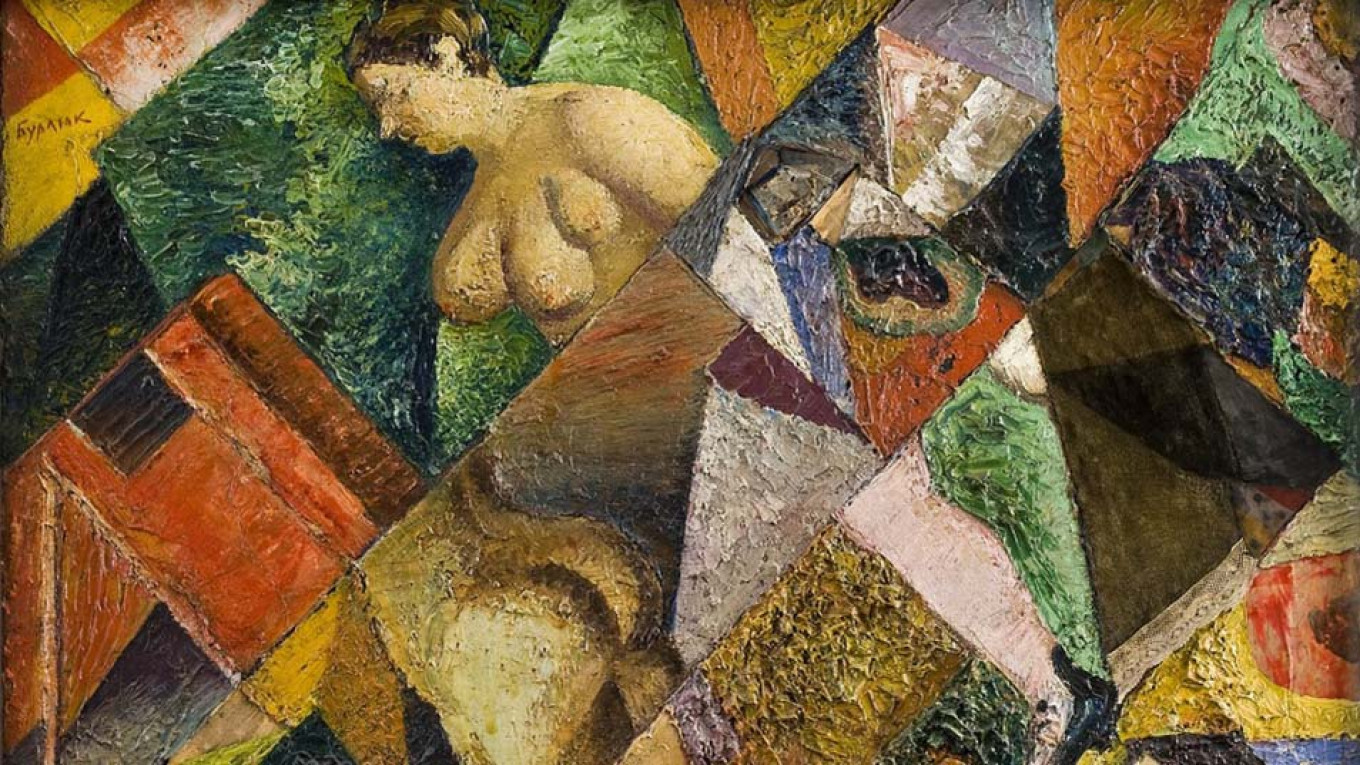

The second hall exhibits Burliuk’s avant-garde period: bold, brightly colored, eclectic blends of styles: impressionism, fauvism, cubism with neo-primitivism. Some works, like “The Reaper,” were designed to be hung on the wall any way, even sideways or upside down. The “Portrait of My Uncle” (1910) is apparently just one of many versions of this painting, which Burliuk was able to sell over and over again as he traveled around the country. “Refugees in Ufa” (1916) and “Family Portrait” (1916), are considered some of the finest works of this period. Note the small canvas placed high above the “Refugees”; this undated “Abstract Composition of the Letter F” is a bit of mischief from the curators, who wanted to imbue the exhibition with the playful spirit of its hero.

The third hall begins with some paintings from Burliuk’s richly productive trip to Japan. Note the futuristic depiction of movement — like blurred motion caught in a photograph — in “The Fishermen of the South Sea” (1921), “Japanese Fisherman” (1921) and “Japanese Woman Harvesting Rice” (1920).

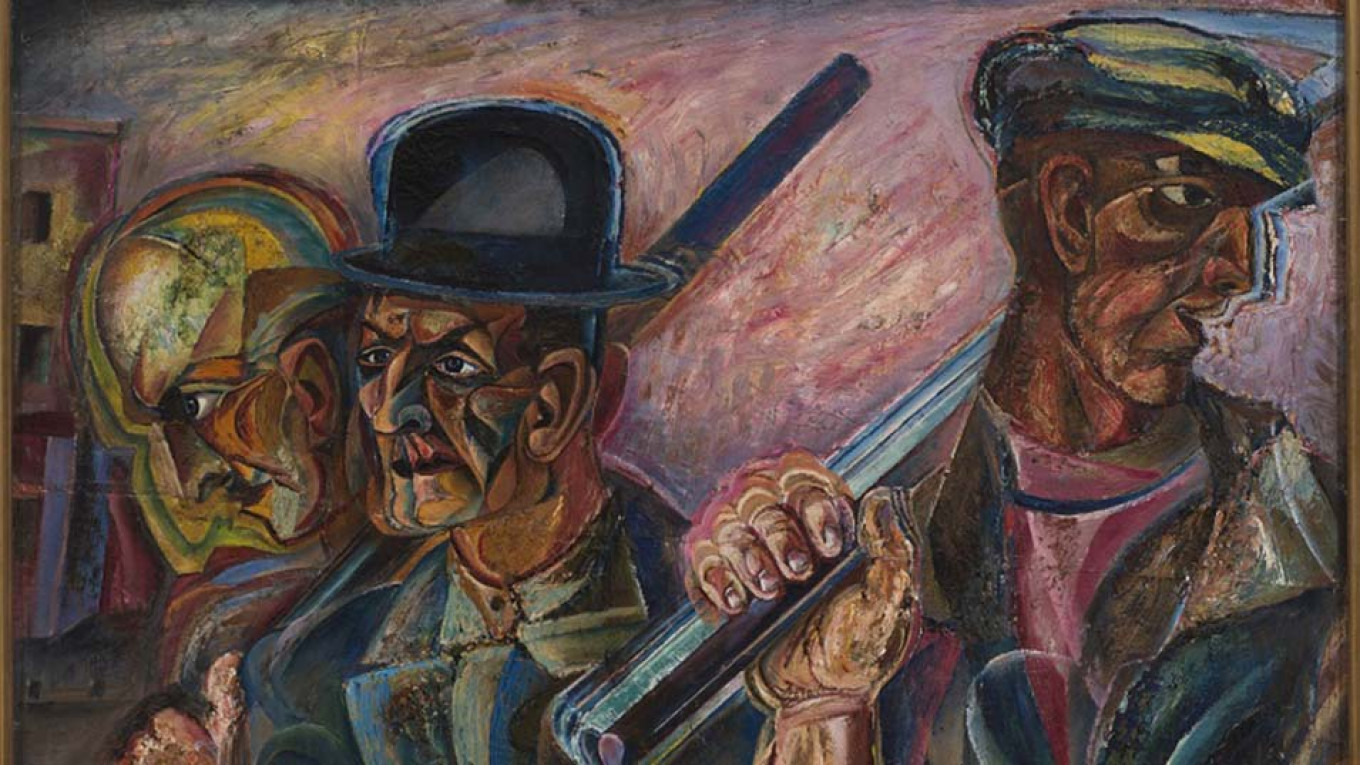

His American period is represented by some works like “Peasants With a Red Horse” (1950) that are primitivist and perhaps a bit nostalgic; Burliuk was sometimes criticized for pandering to a slightly kitschy nostalgia for old Russia. But the grand piece from his U.S. period is “Workers,” painted not long after Burliuk arrived in America. The painting of men building skyscrapers in Manhattan was shown only once, in 1926 in Philadelphia at an exhibition in honor of the 150th anniversary of the American Revolution. No one bought the painting, so Burliuk rolled it up and tucked in the attic. He rediscovered it only in the 1950s. Most of it was irreparably damaged, but he salvaged a section and repainted some of the faces. For this show, the company WOWlab, headed by the artistic project director Alexei Liusik, virtually constructed the painting based on the single photograph taken at the Philadelphia exhibition. This reconstruction can be seen by holding one of the two tablet computers up towards the fragment displayed on the wall.

The last section of the show exhibits a few of Burliuk’s handmade books. Be sure to find the spot across from the books where you can hear Burliuk’s voice, recorded on one of his trips to the Soviet Union. It is a fitting way to end the show.

The show runs through Jan. 27.Museum of Russian Impressionism. 15 Leningradsky Prospekt, Bldg. 11. Metro Belorusskaya. www.rusimp.su.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.