The Kennedys of Boston were and still are America's First Family. Joseph and Rose's third son, Robert Francis, was and still is the most mysterious and alluring of their nine extraordinary offspring. He started his professional life as a cold warrior, driven in part by what he saw in the early trip to Russia described in the excerpts published here. By the end, Bobby was his nation's hottest-blooded and most promising reformer. He was precisely the tough liberal -- or perhaps tender conservative -- that his countrymen seemed to long for when, on the eve of his most decisive victory in his campaign for president in 1968, he was assassinated.

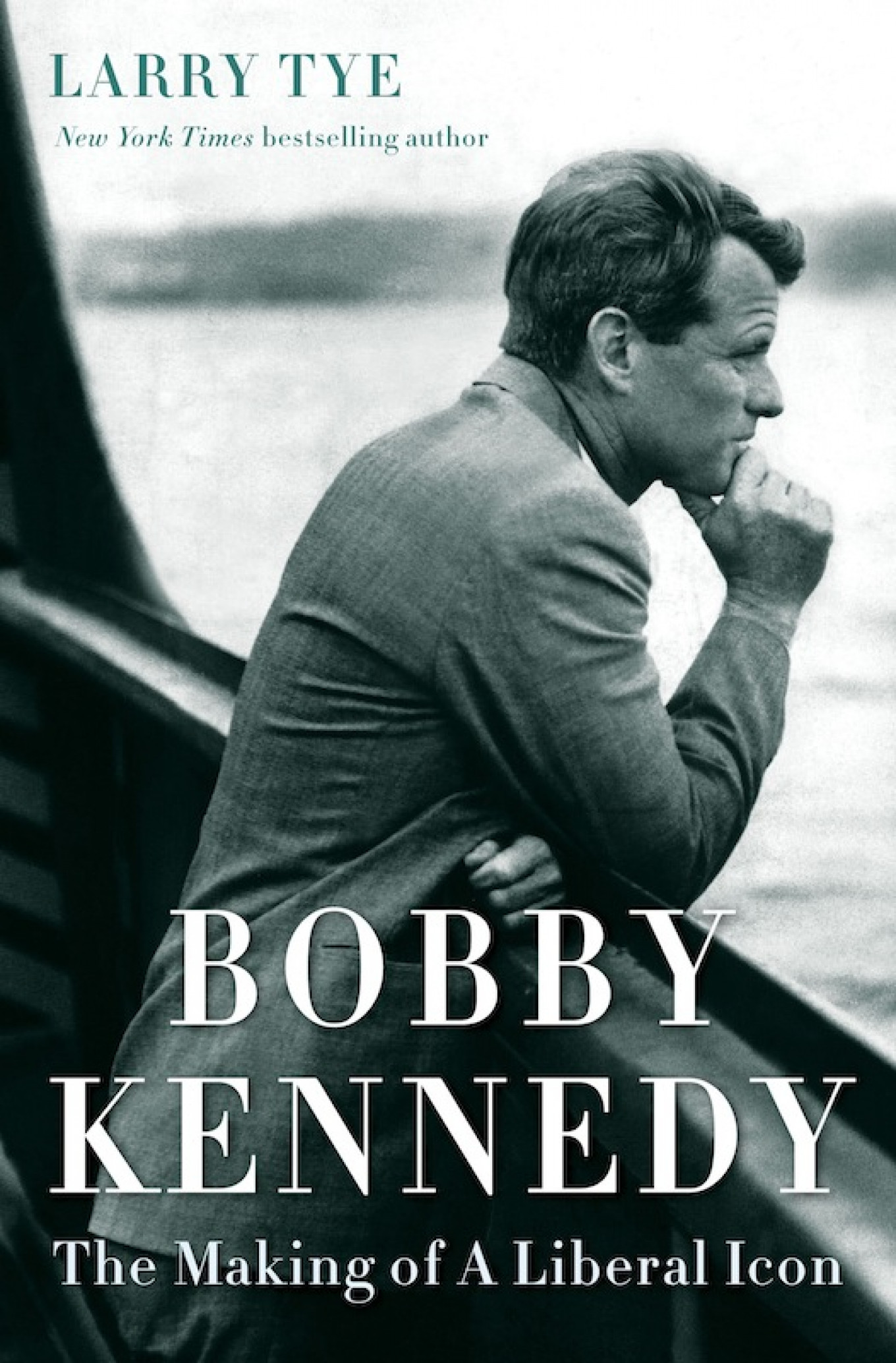

Larry Tye, a former reporter at The Boston Globe, explores in his new book Bobby's political and personal transformation, looking for the keys to his rise as a liberal icon and the messages his life offers to a country as divided politically as it was in Bobby's era half a century ago.

Tye's book – Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon – has been released July 5 by Random House, and is available at Amazon.Com and most bookstores.

Hours after Robert F. Kennedy completed his hearings on Air ForceSecretary Talbott in the summer of 1955, the young U.S. Senate investigator ran to catch a plane to Paris, then another to Teheran, where he met Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. From there the two headed off by car, then ship, finally arriving in Baku, the biggest city on the Caspian Sea. Douglas had interrupted a globe-trotting trip with Mercedes, his bride of six months, for the detour with Bobby. For the next six weeks they toured factories, libraries, and any place they could talk their way into throughout Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and other outposts of Soviet rule. The unlikely duo of the fifty-six-year-old justice and his twenty-nine-year-old ward were the first westerners and one of the stranger sights most of the locals had seen.

The interlude itself said a lot about Bobby. It was the kind of break only someone with Kennedy resources and contacts could consider, since it meant taking two months off from his relatively new job, paying out of his own pocket for transportation and other expenses, and having as his only companion one of the most influential men in America. It also was just the sort of excursion Papa Joe Kennedy had hoped for, with Bobby traveling in the rough and seeing for himself the post-Stalin Soviet state. Joe considered adventures like that better training than his boys would get in college or a job, and he foresaw dividends, as he wrote Bobby: “I think that the value of the trip, besides adding stature to your background, is the article and lectures you might give on it. . . . As I have said a thousand times, things don’t happen, they are made to happen in the public relations field.” To make sure things did happen, Joe also wrote to the Boston public relations maven Eddie Dunn: “When [Bobby] returns from this trip through Russia’s provinces he will have a background that will need some building up. . . I would like you to give some consideration to it and I am enclosing my check for $1000 as a retainer. I hope this will be satisfactory.”

Joe got all that he paid for. The New York Times printed seven stories on Bobby’s travels, starting before he left and ending with a picture of him arriving home with his wife Ethel, who met him in Moscow. The next spring Bobby wrote his own three-page version for the Times under the headline the soviet brand of colonialism. In a fourteen-page interview in U.S. News and World Report, he talked about what he saw: Russian soldiers doing manual labor, “which is something you don’t see in this country”; a museum in Leningrad “devoted completely to ridiculing God”; and, across Central Asia, “the average local person lives in a mud hut, with a mud floor.” A month after his return he gave a lecture at Georgetown University. The Russian government had electronic listening devices in his hotel rooms, Bobby said, and the state selected all the books in the libraries. “All I ask,” he concluded, “is that before we take any more drastic steps [toward détente] that we receive something from the Soviet Union other than a smile and a promise—a smile that could be as crooked and a promise that could be as empty as they have been in the past.”

Justice Douglas, not surprisingly, had a different take on the Soviets and found his mate wearying. “At almost every stop and at every introduction, Bobby would insist on debating with some Russian the merits of Communism,” Douglas recalled. “The discussions were long, sometimes heated, but as I told Bobby, they were utterly fruitless because he could no more convince them than they could convince him.” Worse still for Douglas, Bobby “carried ostentatiously a copy of the Bible in his left hand. And he spent his time on the planes not going over Russian agricultural or industrial statistics, but reading the Bible.” Having refused to eat or drink most of what was offered along the way—even the caviar—Bobby became deathly ill near the end of the trip, with a temperature Douglas estimated at 105. Kennedy wouldn’t let any Russian doctors examine him, but by then he was becoming delirious and Douglas summoned one anyway. It took three hours for the physician to get there, and when she did she administered massive doses of penicillin and streptomycin. “That dear lady never left Bobby’s room for thirty-six hours,” Douglas reported. “When she emerged, her eyes were bright and she said, ‘Now he’ll be all right.’”

The KGB kept tabs on Bobby in Russia the way Hoover’s FBI increasingly was doing back home, and it was equally unimpressed with this young son of a family both organizations would come to know intimately. “Kennedy was rude and unduly familiar with the Soviet people that he met,” the Russian spy agency reported to the Kremlin — an observation that reflected cultural differences as much as Bobby’s idiosyncrasies. He took pictures of crumbling factories, shabbily dressed children, inebriated officers, and other scenes intended “to expose only the negative facts in the USSR.” In meetings with government officials he “posed tendentious questions and attempted to discover secret information.” Lastly, the KGB report said, “he has a weakness for women”and asked his Intourist handler to dispatch to his hotel room a “woman of loose morals” (the report didn’t say whether the handler obliged).

But that was not the full story of Bobby’s travels. His detailed journal entries did focus on Russian vulnerabilities, but he also included a section marked “good things” that described the proliferation of libraries and schools and an amnesty for criminals. His simplistic Cold War take on U.S.-Soviet tensions became more nuanced. Rather than a scattershot attack on Soviet crimes he zeroed in on a question few were asking then: Where were the million Kazakhs and other Central Asians who had vanished during the drive to replace individual land and labor with collective farms? (Answer: Some had been killed, others were in gulags.) He also pointed a finger at the West, saying it could not credibly attack Soviet colonization of areas like Central Asia while it had its own colonies in Asia, Africa, and elsewhere. “We are still too often doing too little too late,” he said, “to recognize and assist the irresistible movements for independence that are sweeping one dependent territory after another.”

This was how Bobby Kennedy learned—by seeing things with his own eyes. Experience enriched and informed his better instincts. He ventured into the most remote of the Soviet republics at the very moment the Warsaw Pact was forming and most Americans were staying as far away as they could. Once there, he filled his journals with engrossing, if not always eloquent, observations. In Iran, he was disturbed by the shah’s proliferation of palaces, calling them “a tremendous waste of land and money.” In the Soviet republics he agonized that “a defendant in a criminal trial can refuse to answer questions but there is an assumption by the judge of guilt. No jury — the judge sits by himself.” His questions drilled deep in a way that could put people off, but they were neither casual nor abstract. He did fight back when new ideas conflicted with one she had long held, which frustrated Douglas and others who mistook it for bullheadedness. It was, instead, the very way he grew and evolved.

By the end of their adventure, the Supreme Court justice had started to revise his opinion of his young companion. “I began to see a transformation in Bobby,” Douglas wrote later. “In spite of his violent religious drive against Communism, he began to see, I think, the basic, important forces in Russia—the people, their daily aspirations, their humanistic traits, and their desire to live at peace with the world.” Mercedes Douglas, who along with Ethel had been waiting for the men in Moscow, was even more impressed with Bobby’s growth. Experience flushed a lot of ideas out of his system — she likened it to an enema — and his trip toRussia represented the “undoing of McCarthyism.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.