The fall of the Soviet Union gave Russians a taste for several freedoms. Some, like freedom of expression and assembly, are no longer taken for granted. Others, like freedom of travel, are — at least by the monied and mobile. In recent years, however, authorities have made it clear that this freedom was no longer automatic for those it sees as undesirable. New proposals to amend Russia's existing terrorism laws, published this month, raise the prospect of such bans being given even wider application.

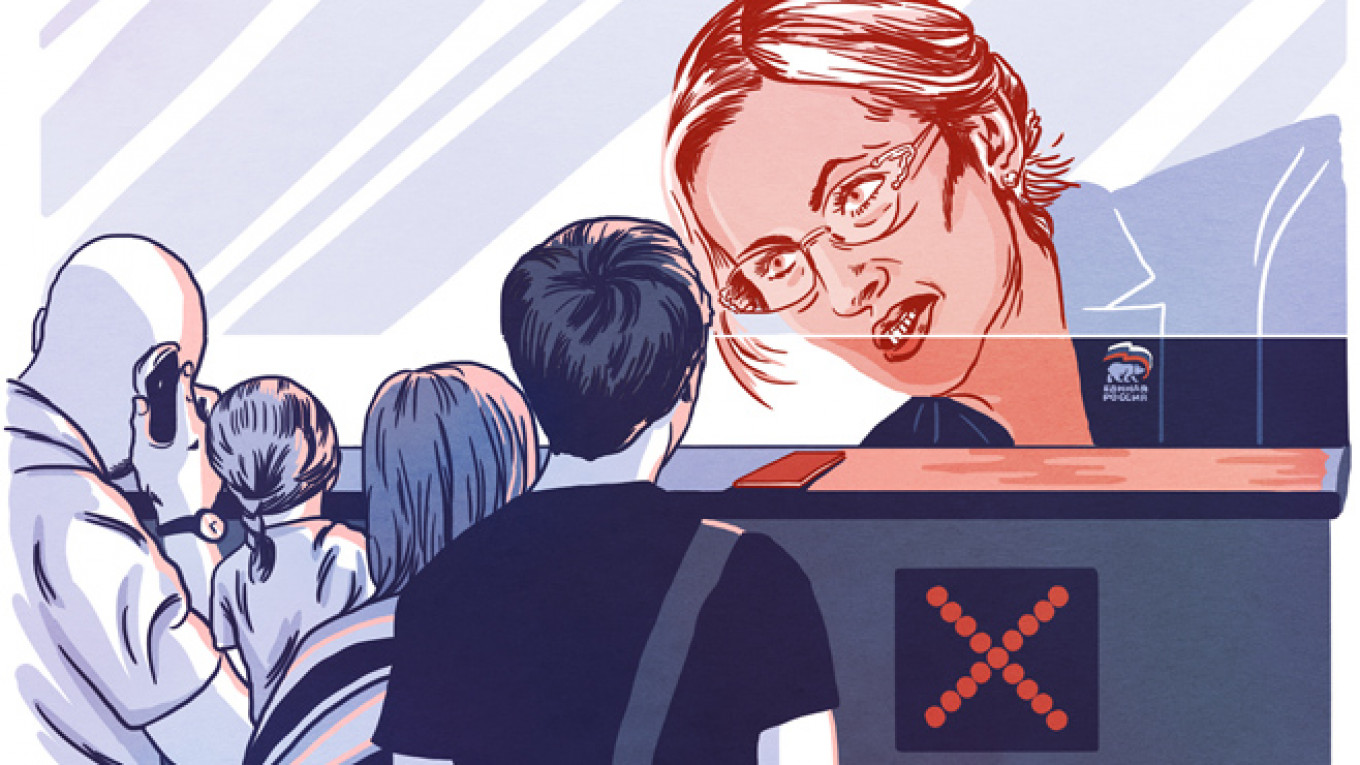

Authored by uber-loyalists State Duma deputy Irina Yarovaya and Federation Council member Viktor Ozerov, the proposals would increase the categories of Russians prohibited from leaving the territory of the Russian Federation. They would limit overseas travel for people who "justify" extremism online and for those officially cautioned for activity that "creates the conditions to commit a crime." Both of these clauses can be actioned without the involvement of a court.

In effect, this could mean any Russian reposting an "extremist" article or Internet post is at danger of receiving an extra-judicial five-year travel ban. Aside from travel bans, Yarovaya also wants to raise the jail sentence for justifying terrorism from five to seven years and lower the age of responsibility from 16 to 14.

Flexible Definitions

The number of Russians charged with the increasingly widely interpreted definition of "extremism" is rising fast.

"Every year, a few hundred Russians are charged for the simple matter of having an opinion," says Alexander Verkhovsky, the director of Moscow's SOVA Center, which monitors abuses of anti-extremism legislation. Verkhovsky believes this particular bill would be a clear limitation of rights, as it would enable authorities to punish an individual prior to a court decision.

Sociologist Denis Volkov from Moscow's independent Levada Center pollster, on the other hand, says the bill is unlikely to make Russians more wary about what they post on the Internet. "Most people are not aware of these laws," he says.

Authors of the proposal say they want to "increase the guarantee of safety and health of Russian citizens." There are some doubts as to whether travel bans can do that, and the potential for the opposite effect is clear. According to Verkhovsky, they "risk further alienating those Russians most prone to radicalization." The legislation's only logical aim, he says, would be to stop Russian extremists from making the journey to Syria.

Russia is, of course, not alone in exploiting anti-terrorism initiatives to broaden state control over citizens. Surveillance and detention capabilities of Western governments are expanding, not least since the Paris and Brussels attacks. But in Russia, the proposed travel ban fits a wider trend.

Those Russians employed by state security services have long been prohibited from travel abroad (for non-work purposes, that is). The Federal Security Service (FSB) made these rules even stricter after 2010, when the United States uncovered its sleeper spy network.

But the list of those affected by travel bans now goes far beyond those with potential access to state secrets — and it is growing steadily.

In particular, the groups subject to travel bans has grown considerably since the start of the war in Ukraine. In 2014, travel restrictions were extended to civil servants in the Defense Ministry, Internal Ministry and the staff of Russia's vast prison service.

The no-fly list now also includes debtors — those avoiding paying back loans or who are behind in their tax payments. During a crisis, an estimated 4 million people are at risk of falling into this category.

Closing Borders

On the face of it, the Kremlin seems to have adopted a change in strategy following the white-ribbon protests in the winter of 2010-11.

In the years immediately following, authorities did much to encourage opposition sympathizers to leave. Many middle-class Russians with opposition ties left Russia for Europe: Riga, London and Berlin have since become liberal Russian hubs. Travel bans were certainly imposed on opposition leaders but some of their most active supporters were free to leave.

But the picture today is changing. The Kremlin has sought not only to control the right to travel itself, but, more broadly, the destinations open to Russians. As a reaction to Western sanctions imposed on Moscow for the annexation of Crimea, Russia's Foreign Ministry advised its citizens not to travel to the United States (government officials have long been asked for permission prior to traveling to the United States) nor the vast list of countries with which Washington has extradition rights.

The Russian blogosphere has erupted in forums with titles such as "am I allowed to travel abroad?" Many now posit the prospect of a Soviet-style exit visa system being introduced. Senior diplomat Vadim Syromolotov has even suggested that the government was considering demanding exit visas for Russians traveling to Europe.

Officially his own employer, the Foreign Ministry, has been quick to deny such plans. The very suggestion of exit visas, however, was enough to raise fears over the future of foreign travel in Russia.

It is unclear the extent to which the Kremlin is willing to go to make Russians stay put, or, indeed, if this is part of a larger effort to reduce exposure to the outside world. But it is also true that most Russians value their right to travel and have little nostalgia for the Soviet-era travel bans. While they may have waved goodbye to other freedoms with a sense of detachment, it may well be that moves to limit their movement will be met with a more emotional response.

Contact the author at newsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.