In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

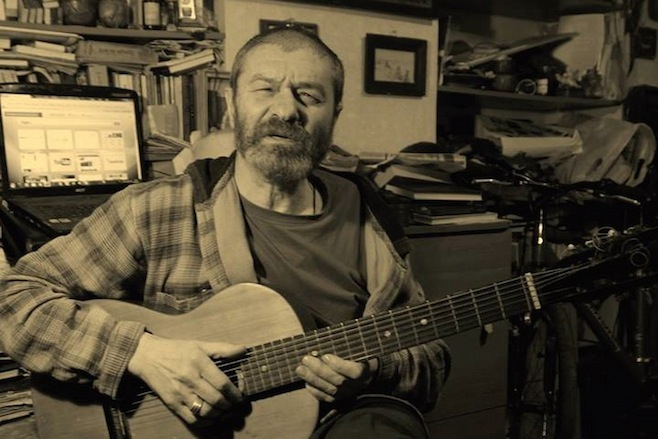

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Oleh Hubar, 61, a city historian, tells his family's story from Odessa.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

I don't identify myself in terms of any kind of nationality or ethnicity. I'm a citizen of the world, if you like.

I was baptized as Orthodox, and in the spiritual sense I consider myself a representative of Russian culture. Although, I repeat, I am absolutely not fixated on the issue of nationality.

Odessa is traditionally a Russian-speaking city. Although before the Bolshevik Revolution, of course, it was very common to hear Yiddish — one out of every three people spoke it.

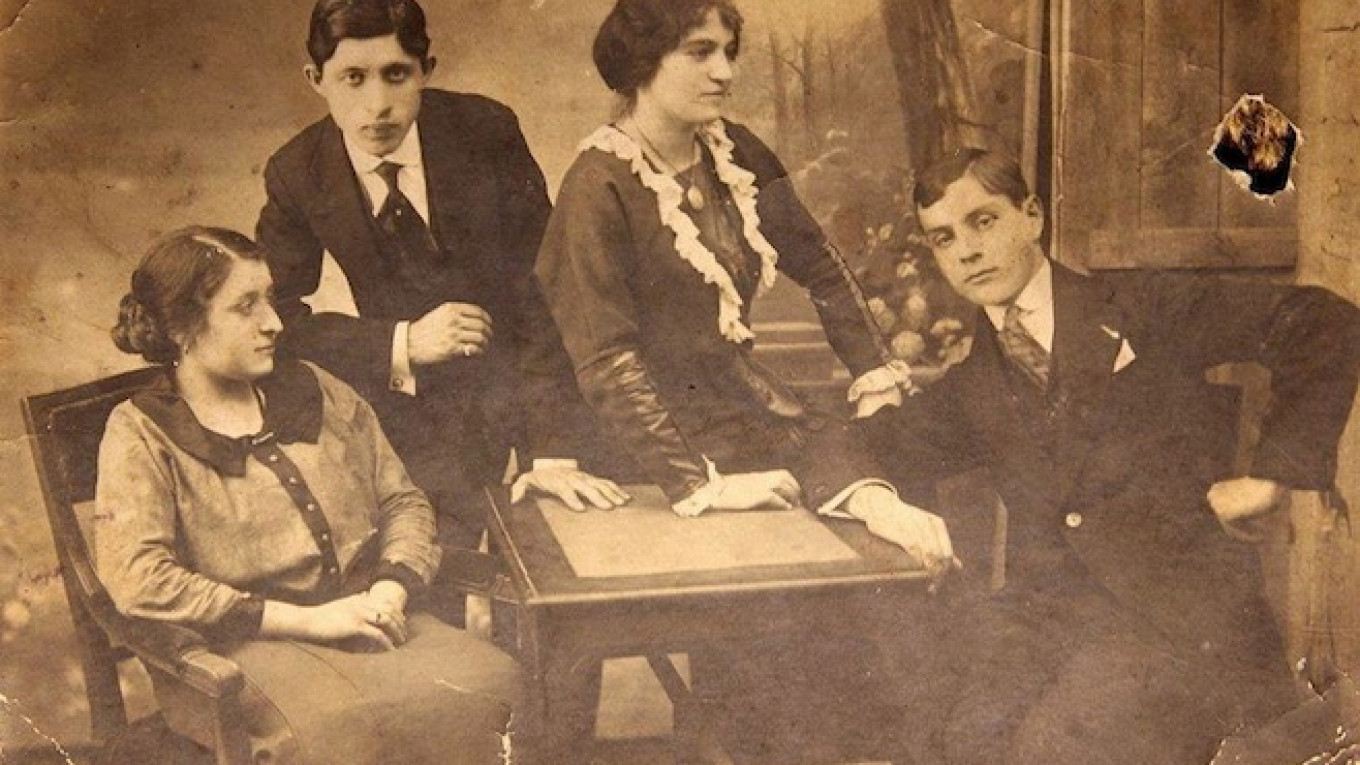

Maria Kazakova, Odessa.

My family is like many Odessa families -- a big mix of ethnicities and religions.

My paternal grandmother, Maria Kazakova, was half Jewish and half Russian Orthodox. She was raised in the household of her aunt, who was married to a school-district official in Odessa.

She ended up marrying Lev Hubar, who worked in the office of a milling company with his father and who fought in World War I. The Hubar family was considered part of the Odessa elite.

The last name is derived from the word "guba," which means a long tract of forest. Mushroom hunters are often called "gubars." I'm a huge mushroom enthusiast, so it all worked out pretty well for me.

My maternal grandmother was also Jewish; my maternal grandfather was a Baltic Sea German.

He ended up deserting from the Russo-Japanese War with a group of other soldiers and went into hiding. He never came back.

We found out later that he had changed his surname from Flaschtatz to Shvartz -- my grandmother's last name -- to help protect his identity. So that was his story. I eventually tracked him down in the archives.

Oleh Hubar's mother, Yevdokia (far right), Odessa, early 1930s. Yevdokia and her cousin Liza (above right) both survived the pogroms of World War II. The two relatives on the left died in the Odessa ghettos.

My mother, Yevdokia, kept her mother's name as well. She was very distinctive-looking. At school, all the other children called her the Japanese Emperor.

She was lucky enough to survive World War II. Odessa Jews were murdered en masse by Romanians and Germans during the occupation. Many were forced into ghetto settlements and left to die from bombings or exposure.

My mother lost almost her entire family. Her closest relative at that time was her older brother, who was killed in 1943 in the Lower Dnieper Offensive, one of the bloodiest battles of the war. His wife and their children died in the ghetto.

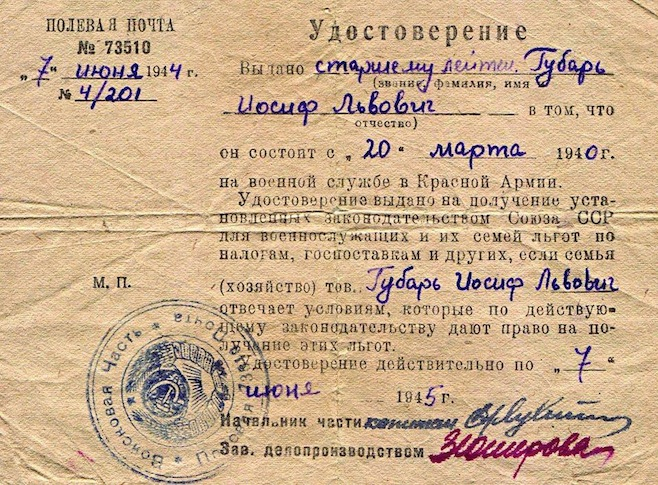

Iosif Hubar, wearing the Order of the Patriotic War.

My father, Iosif Hubar, served in World War II as a senior lieutenant in the Soviet Army. He was decorated after his unit "scattered and liquidated" four German platoons.

My family has always taken a critical stance toward government. But we were never among what I would call the constructive opposition.

We weren't apologists, but we weren't total detractors, either. We always tried to view everything in a rational, sober manner.

Regarding the current situation, I can say that the war isn't being fought in the east. It's certainly not being fought in Odessa.

It's being fought at a much, much higher level. And we — ordinary people — are nothing more than bargaining chips in a big game.

Certification of Iosif Hubar's service in the Soviet Army. This document allowed his mother to receive special tax benefits and food-supply rations.

It's not worth demonizing anyone in this war, because our leaders are equally bad. Each works for his own interest, and one isn't better than the other. The worst is that so many people are dying because of it.

I've had many opportunities to leave Odessa, to leave Ukraine. All my relatives left. My father, mother, and sister Inna all died in the United States. My uncle and aunt did also. And all their children live there.

I'm all alone here. But I'm a sixth-generation Odessa native. I don't want to leave.

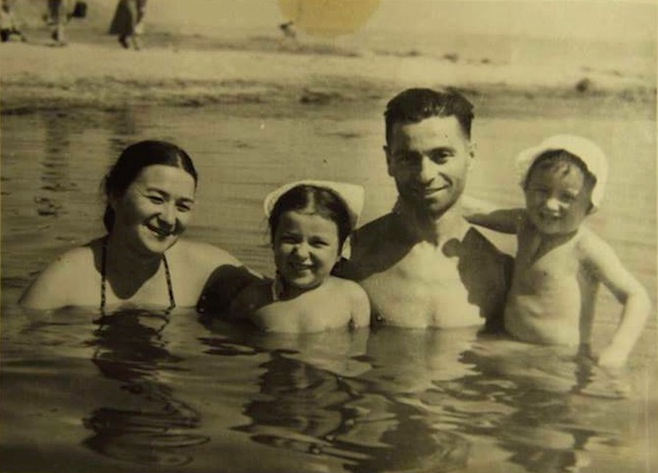

Yevdokia, Inna, Iosif, and Oleh Hubar swimming in the Khadzhibey Estuary outside Odessa, mid-1950s.

Someone needs to stay behind to visit the graves of their ancestors.

And in general, this is my city. I don't need any other. My grandmother is buried here, my teacher, my father's younger sister Olga, in whose honor I was named. And many others. I want to be with them.

Oleh Hubar

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.