In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Lilia Bigeyeva, 55, a violinist and composer, tells her family's story from Dnipropetrovsk.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

I'm a mix of Tatar, Ukrainian, and Russian — the secret formula for very voluble, artistic types. I'm a person of big emotions.

My great-grandfather was Musa Bigiyev, a Volga Tatar who was the first person to translate the Koran into Tatar. (My name is spelled slightly differently.) He promoted a very modern form of Islam. He believed in education for women, and he and his family always dressed in European-style clothing.

He was friends with Lenin and he worked with the Bolsheviks. He even served as the first imam at the St. Petersburg mosque. But after Lenin died he was basically driven out of the country. He died in Cairo.

Another one of my great-grandfathers was an Orthodox priest in Ukraine. He was sent to a prison camp in the 1930s and never heard from again.

There are a lot of photographs of my Tatar great-grandfather, but absolutely none of my Ukrainian great-grandfather.

One of Musa Bigiyev's sons, Akhmed, was married to my grandmother, Tatyana Volodina, who was an extremely talented Russian pianist. They lived in Russia, in Vologda, but when the repressions started against Musa, Akhmed was thrown in jail. That's how it was done -- the whole family had to suffer.

Tatyana was seven months pregnant at the time, and she knew what it would mean for herself and her children to be related to an enemy of the regime.

Tatyana Volodina. Lilia's father, Iskander, is on the right.

She was very lucky to have a friend who worked at the marriage-registry office, which also registered divorces. Her friend was able to change a document to make it look as though Tatyana and Akhmed had gotten divorced.

It didn't make his family very happy. But I feel like she had to do it, to save herself and her two sons. The Soviet system forced people to make very desperate decisions sometimes.

Tatyana took her children and moved to Ukraine. She was an amazing pianist and composer and performed her entire life, up until she was 85. She had incredible hands. I think I have her hands.

Lilia's mother, front and center, Melitopol, 1940.

My mother was born at a time when a lot of children were getting idiotic names like Nenil and Traktorina. But she was named Aelita, after the great science-fiction novel by Alexei Tolstoy. People usually just called her Alla.

This picture was taken at the start of World War II; that's probably why the children are wearing military costumes. Melitopol was occupied by the Germans and saw a lot of destruction. It's possible some of these children weren't alive a year later.

I was born in Melitopol, raised in Zaporizhzhya, and have spent all of my adult life in Dnipropetrovsk. It hasn't been easy, this past year in Ukraine. The loss of Crimea is a tragedy, the war is a tragedy. And it's far from clear that our government and our people are really prepared to institute rule of law.

But I would never consider leaving Ukraine. One of the reasons is my Uncle Leonid.

His father was the Orthodox priest who disappeared in the labor camps. Leonid was arrested during World War II, and as soon as he was released, he left for the United States. He lived there for 10 years, someplace in Ohio -- we don't even know where. Sometimes he sent pictures.

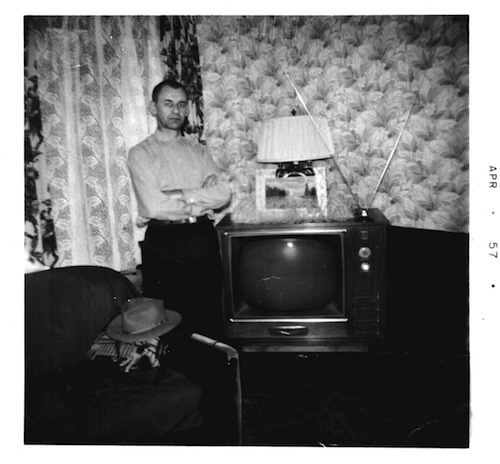

Uncle Leonid, somewhere in Ohio.

From all appearances, he lived well. He was an economist and he rented a room in a house with a television that was enormous, by our standards. But as soon as he had the possibility to come back, he did it without hesitation.

We barely had indoor plumbing at the time, let alone gigantic televisions. But he never regretted it. He told me a story about his American landlady borrowing a dollar from her son and the son charging interest when she paid it back. Leonid told the story without any particular emotion, but to me it was horrifying.

Iskander and a colleague, wearing fake noses, Zaporizhzhya, 1960s.

People think there was no laughter behind the Iron Curtain, but there was a lot! My family was always dressing up in costumes, putting on performances.

That's how we celebrate birthdays even now. I don't need jewelry or some kind of name-brand cognac; I just want my friends to come over and say, "What kind of nonsense are we going to get up to tonight?" We put on little plays, we sing, play music.

My parents both worked at the Zaporizhzhya Abrasive Plant, a huge factory at the time, and they were active in humor competitions and performances put on by the staff. We always had crowds of people over at our house rehearsing. It's funny to hear experts now talk about how to boost morale at work.

Lilia as a little girl. "I never got my ears pierced, and I don't wear rings.

When you play violin, jewelry just gets in the way."

Every member of my family studied music or dance in some form. It helps you unlock your creative side, even if you end up doing something completely different.

I started playing the violin when I was 7, and I started composing when I was 13. I've spent many years as a music teacher as well.

Lilia Bigeyeva (back row, center) with her pupils, 1980s. "Children today seem too busy. To study music, you really need to be calm."

I've seen a lot of my pupils grow up and become professional musicians. Others go on to other jobs but still enjoy playing music; others give it up completely and never look back.

The war is very close to us, here in Dnipropetrovsk. Every day there's bad news. But we continue to play music, my pupils and I. Culture and art, these are the things that have always helped us through frightening times.

The hallway outside Lilia's top-floor apartment is covered in mosaics she crafted from CDs, bottle caps, and stones and beach glass brought from summers in Crimea. She was furious when one of her neighbors stapled a satellite cable over one of her creations. "Animals!"

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.