SIMFEROPOL, Crimea — Ukrainian Orthodox Christians who are loyal to Kiev feel increasingly unsafe in Crimea after Russia's annexation of the Black Sea peninsula and some have already left, church leaders said.

Since the Soviet collapse in 1991 and the advent of an independent Ukraine, the country's Orthodox faithful have been split between the Kiev and Moscow Patriarchates. The much larger Moscow-based church does not recognize its Kiev-based rival, which is not part of the global Orthodox communion.

The estimated 220,000 Crimeans loyal to the Kiev Patriarchate have long felt marginalized because of the region's strong pro-Russian sympathies, but Moscow's takeover of the peninsula has fueled their feelings of vulnerability.

Their misgivings echo those of another minority, the Crimean Tatars, a mostly Muslim Turkic people, about Russia's annexation. Crimea's majority ethnic Russian population voted strongly in favour of joining Russia in a March 16 referendum branded illegal by Kiev and the West.

"The families of our clerics have all left, the clerics are still here but they will also leave immediately if forced to take a Russian passport," community leader Metropolitan Kliment said by telephone from an undisclosed location.

"Our churches could be thrown out onto the street today or tomorrow because we are not in line with Russian laws," said Kliment, who said he had already left Crimea himself due to safety concerns.

Kliment said the patriarchate's only church in the port city of Sevastopol was now effectively shut because it sits in a Ukrainian military base now controlled by Russians "who don't even let the priests in at times, not to mention anybody else."

Trading Accusations

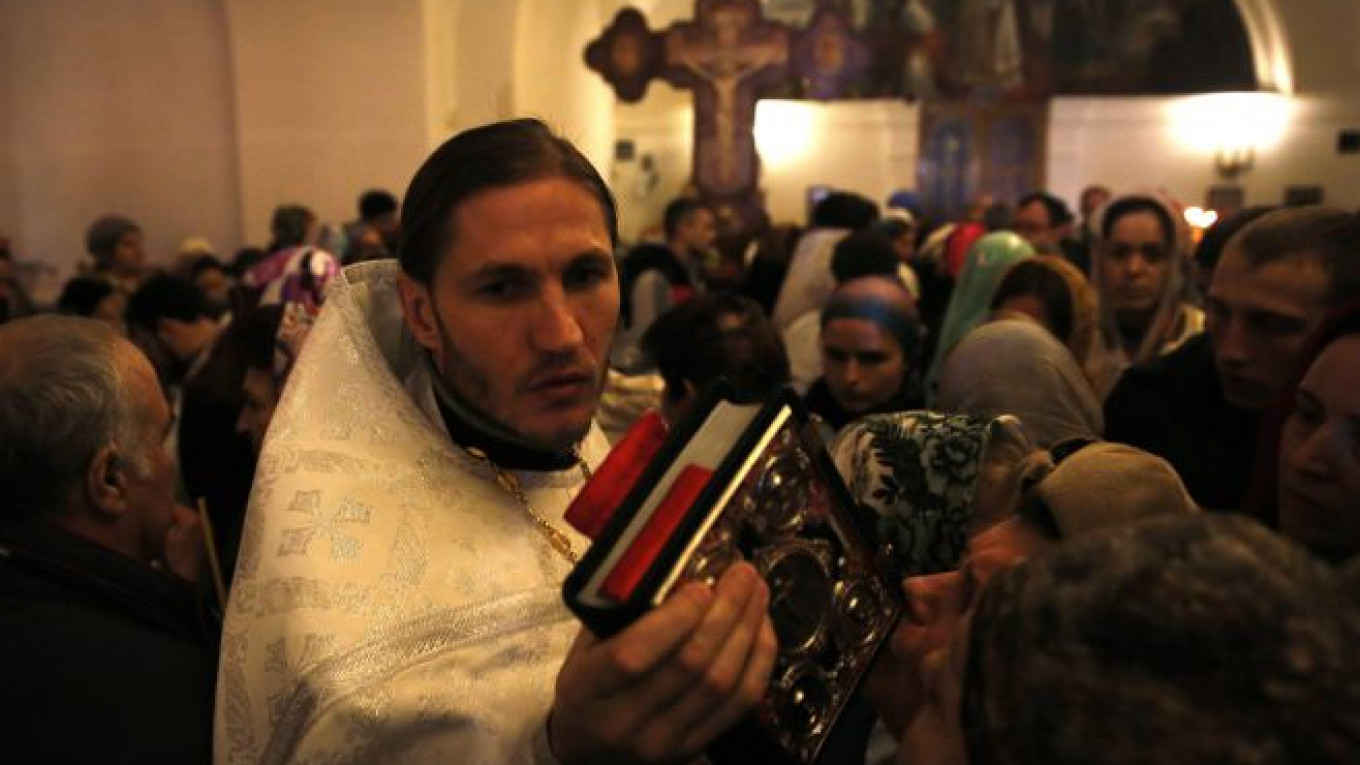

The rival patriarchates and their followers have exchanged accusations in Crimea, with some loyal to Moscow accusing the Kiev-allied priests of trying to run away with church property including revered icons and other religious objects.

Those loyal to Kiev have said clerics serving under the Moscow Patriarchate have sought to take over their churches and had sometimes been accompanied by Russian soldiers to enforce their message.

Russia has cited alleged threats to worshipers of the Moscow-backed church in pressing its right to send in troops to Ukraine to protect its nationals and Russian speakers. Patriarch Kirill, head of the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow, has close ties to President Vladimir Putin.

Patriarch Filaret, the head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Kiev Patriarchate, said in Kiev on Monday that Crimea's new Russia-backed authorities had offered written assurances that his community would be left in peace.

But "it's hard to believe promises at the moment," Filaret told a news conference. "They promise one thing and then do something else, so if they don't fulfill their promises we will take the Crimean Muslims up on their offer."

Mosques Open to Orthodox Believers

In an unusual inter-faith gesture of solidarity, Crimea's Muslim Tatar minority has offered to allow Kiev-loyal Orthodox Christian worshipers to hold services in their mosques.

The 300,000-member Tatars, who make up less than 15 percent of Crimea's population of 2 million, are haunted by memories of Moscow's mass deportation of their community to Central Asia in 1944, during World War II. On Saturday, they called for "ethnic and territorial autonomy."

In Simferopol, where the Kiev-loyal Orthodox church is headquartered, Father Volodymyr said services were being held as usual for now but added congregations were noticeably smaller.

"Fewer people are coming because some families, especially those with small children, have left," he said by phone.

Archbishop Kliment has banned priests speaking to media in person due to security fears. The Kiev patriarchate has 20 churches in Crimea presided over by 15 priests.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.