The Russian stock market has staged an impressive recovery, rallying 18 percent from its summer lows. But this rally has defied economic performance and has clearly been driven by global factors. A global macro rally is certainly welcome, particularly as Russian stocks continue to trade at near-record discounts, but what are the perspectives for domestic drivers as we enter the final quarter of the year?

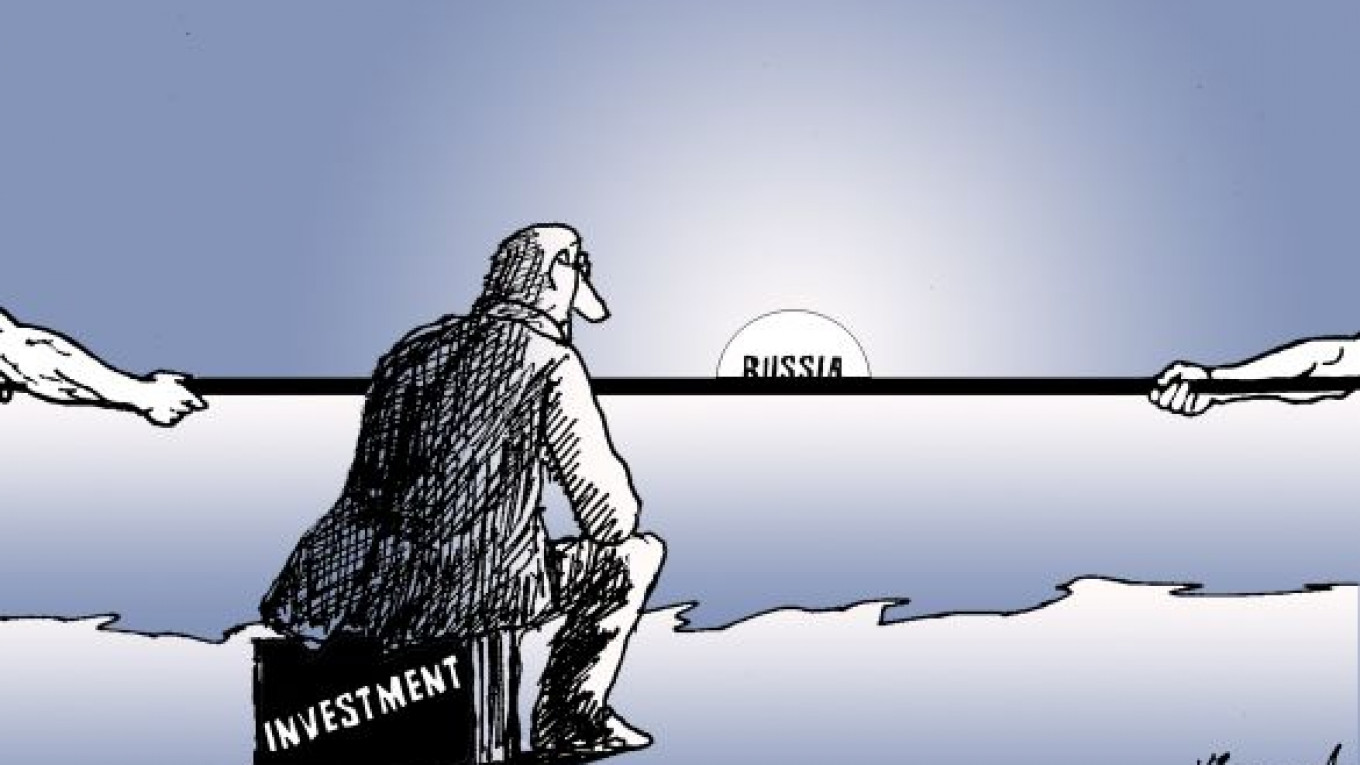

As usual, two clear factors are responsible for determining the prices of Russian assets relative to their global peers: economic fundamentals, which determine the profitability of Russian businesses, and political issues, which determine the discount at which they trade. For most of this year, the picture has been bleak on both fronts. Even more concerning, economics and politics are now beginning to merge in the form of declining investment.

Declining investment levels suggest that political risks have begun to hamper fundamentals, but September’s mayoral election and a shift on Syria raise new hopes.

Russia's government sector is already bloated and inefficient, and the consumer has been carrying the economic torch for far too long. As a result, economists and investors universally agree now that an improved investment environment is essential to restore growth to potential.

Why, then, has investment in productive capacity declined from 17 percent in March 2012 to minus 4 percent today? Of course, many factors help explain this collapse, not least the apparent ending of the commodities super-cycle and the desperate recession in the European Union, Russia's key trading partner. But local factors are important, too. After all, Russia's domestic economy lags notably behind many of its post-Soviet peers in terms of transition, so there should be domestic drivers to offset international woes.

The key local problem is highlighted in research by global investment banks, which shows that Russia's investment-risk level, relative to its peers, has been elevated for much of the country's capitalist history.

For most of its capitalist history, but not all of it. In March 2008, when Dmitry Medvedev was elected president with a modernizing agenda, Russia's relative risk level turned negative. Of course, it spiked again during the war with Georgia and the global credit crunch. But it remained negative for most of Medvedev's presidency and only turned positive again the month that the market understood Vladimir Putin would return to power. With that so-called castling maneuver, Russia's future went from uncertain, but hopeful, to stable, but concerning — at least in the minds of many foreign investors.

This is not to cast unconditional disdain on Putin's contribution. Clearly, Russia's modern risk profile, with its balanced budgets and massive rainy day funds, is better than it was in the 1990s under then-President Boris Yeltsin. But 2013 is only the second year of Putin's six-year term, and the investment community is already entrenched in discussions about whether or not he will stand again.

Investment projects have multiyear payback times, and investors need confidence that stability will hold up throughout. As much as Putin has brought stability to Russia, concerns about how and when he will transition out of power are already holding back growth and propping up risk premiums. Fortunately, events in September brought real hope, and already in October there is a chance to see clear follow-through.

The Russian government made a solid first step toward tackling elevated political risk when it allowed competition in the Moscow mayoral election. True, this was done on loaded terms, where the victory of the Kremlin favorite was assured. But even so, the decision to accept competition from charismatic opposition leader Alexei Navalny and to allow an essentially fair vote was a cosmic leap forward. Of course, Navalny lost, and, of course, his appeal against the result was rejected. But he surprised many by not calling his troops to the streets in response. Russia now has a leader building a reputation for constructive pro-Russian opposition to the Kremlin.

Also in September, Putin unleashed what the Western media have labelled a political coup against the U.S. by persuading Syria to avert imminent military intervention by surrendering its stock of chemical weapons. The investment returns connected to Syria are low in the Russian market. But one should not underestimate the potential benefit of Russia tackling its caustic anti-Western reputation on the global stage. Emerging markets have been booming for a couple of decades now, but the investable reserves of the West and Japan quantitatively outweigh those of their emerging-market counterparts. Developing a constructivist role in the global political arena could greatly improve Russia's reputation as a potential destination for capital flows.

The opportunity for follow through on these big steps forward comes this month, as Navalny returns to Kirov to appeal his conviction on embezzlement charges. If Navalny's conviction is upheld, even with a suspended sentence, he will be prevented from running for office, and the opposition movement will be pushed back to square one. Protests are likely and investors will reset their Russia-risk monitors to reflect elevated concerns once more. Capital investments will again be pushed back because however good Putin is, he can not live for ever, and no one will have any clarity about how Russia will adjust after he has gone.

Alternatively, the appeals court could overturn his conviction, in which case Russia would have a chance to argue that its legal system is improving. The opposition movement would keep its most-talented leader, and the Kremlin would have given him the green light to campaign with a mandate for change.

Of course, the risks will remain high in Russia regardless because innumerable problems will remain, and the Kremlin continues to enjoy a stranglehold on the key media outlets. But Russia would still be opening the doors to progress and reform. This would diminish the probability of worst-case, long-term outcomes and enhance hope that Russia will use its enviable fiscal position to bring modernizing reforms that allow it to achieve its great potential.

James Beadle, an independent investment manager serving high net worth individuals, is currently based in Monaco.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.