Vladimir Putin, peacemaker.

Such a title would have seemed almost unimaginable even a few weeks ago for a man who rose to power in part by waging a bloody war in Chechnya, where he vowed to "rub [the rebels] out in the outhouse."

But with his foreign minister pushing a diplomatic solution to the problem of chemical weapons stockpiles in Syria in order to avoid a military strike by the U.S., and with Putin throwing his political weight behind the plan, the Russian president is suddenly being lauded for his ambassadorial prowess.

In an op-ed published Thursday on the pages of The New York Times addressed to "the American people and their political leaders," Putin defended his strict opposition to military intervention in Syria, calling instead for renewed efforts to bring the conflicting sides in the civil war to the negotiating table.

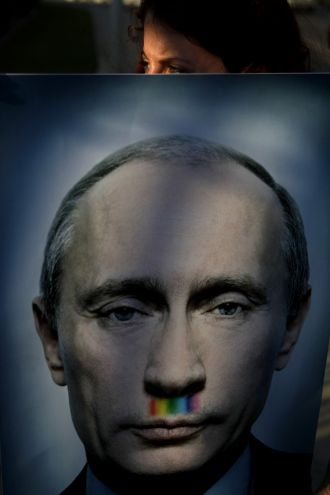

A demonstrator at a protest in Nicosia holding up a poster of Putin.

"From the outset, Russia has advocated peaceful dialogue enabling Syrians to develop a compromise plan for their own future," Putin wrote. "We are not protecting the Syrian government, but international law."

"We need to use the United Nations Security Council and believe that preserving law and order in today's complex and turbulent world is one of the few ways to keep international relations from sliding into chaos."

The success of Putin's campaign against a U.S. military strike is not guaranteed. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was set to meet with his U.S counterpart John Kerry in Geneva on Thursday and Friday to see if they could begin nailing down a plan that would allow for Syria's chemical weapons to come under international control and later be destroyed. (See related story, Page 2.)

But some analysts have already called this the pinnacle of Putin's time at the helm of the Russian state. In addition to appearing in The New York Times, Putin was the focus of a cover story in iconic Time magazine for a second time this month. U.S. congressman Brad Sherman told reporters this week that the Syria plan "was the best thing to come out of Russia since vodka."

Back home, pro-Kremlin youth group Nashi has already called for Putin to be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, while protesters in Moscow have said U.S. President Barack Obama should be deprived of his own Nobel award.

"Obama threatens war, while Putin saves the world. That's the 'division of labor.' And who is more deserving of the Nobel Peace Prize? The contrast does not favor Obama," tweeted pro-Kremlin State Duma Deputy Alexei Pushkov on Thursday.

Just a few weeks ago, Putin was being lambasted around the world for signing an anti-gay law that critics say de facto bans gay pride rallies or even public displays of affection by LGBT people.

Some called for countries to boycott the Winter Olympics in Sochi next year because of the law, and signature "Russian" products, such as Stolichnaya vodka.

For now, that criticism seems to have been forgotten. Putin's op-ed on Syria seems to have struck a nerve among many readers, with several of the most popular comments to the article praising Putin and the position he laid out, sometimes in effusive terms.

"Say what you will about the Russians and Mr. Putin in particular. This reaching out is unprecedented," read a comment "liked" more than 1,000 times, by an unnamed "Citizen" of Texas.

"Sur[e]ly our country and our leaders cannot ignore this gesture from the Russian government. We, at the very least, should meet this offer in sincerity and in the hope, that something good and lasting will come of the discussions between our two nations."

Putin pictured on the cover of Time.

Putin put forward his usual legalistic stance in the article to argue against the use of force on the army of Syrian President Bashar Assad. He said the move would only exacerbate the situation and make the conflict spill over Syria's borders, making surrounding states more reluctant to give up plans of developing nuclear weapons.

He also warned that "Syria is not witnessing a battle for democracy, but an armed conflict between government and opposition in a multireligious country," expressing his usual skepticism of U.S. efforts to export democracy around the world.

Alexei Malashenko, scholar in residence at the Carnegie Moscow Center, argued that Putin would be in a strong position diplomatically if he succeeds in helping push through the plan to eliminate Syrian chemical weapons and thereby averting a U.S. strike.

"If Putin prevents the conflict in Syria, he will be the winner, even the triumpher," Malashenko said. "He will reap as many benefits from this situation as he can and then use them in Russia negotiations."

By putting forward such a shrewd plan for Syria and appealing to the large group of Americans that is tired from more than a decade of foreign wars, Russia may make itself more acceptable in the world as a pole of power, Malashenko said.

With these latest efforts, Putin appears to be attempting to show that he is not "the bored kid in the back of the classroom," as Obama once referred to him, but the leader of a country that wants to reclaim its superpower status.

"This was a most unusual letter, which has taken Russia-watchers and critics by surprise. Many of them now have to reassess their earlier approaches," said James Nixey, head of the Russia and Eurasia Program at London's Chatham House. "For the very first time we see a move that has to be regarded as a positive one."

While most seem to agree that Putin has won this round between himself and Obama, the fact that the U.S. and Russia are currently working together on a Syria plan could signal a turning point in bilateral relations that were gradually deteriorating.

‘To be honest, we are not seeing some cozy new Russia that is a force for world peace.’

James Nixey

Analyst

Following a series of spats, Obama canceled a visit to Moscow scheduled for earlier this month, citing the absence of a constructive agenda. At the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg last week, the two leaders met anyway, to discuss possible solutions to the Syria conflict, including the idea of bringing the Assad regime's chemical weapons under international control.

Pundits point out that Putin has a variety of motives for taking his current diplomatic approach. In addition to possibly seeking the image of a peacemaker by grandstanding, he is aiming to prevent American meddling in the Middle East and an explosion of extremism that could eventually come to inflict harm on Russia, especially in the volatile North Caucasus.

"To be honest, we are not seeing some form of new cozy Russia that is a brand new positive force for world peace," Nixey said. "We are still looking at a situation where Putin wants to see Russia as different and specific."

Anna Neistat, an associate director at the U.S. advocacy group Human Rights Watch, argued that Putin's words were hypocritical given Russia's record on upholding human rights.

"The sincerity of Putin's talk about democratic values and international law is hard to take seriously when back home his own government continues to throw activists in jail, threatens to close NGOs, and rubber-stamps draconian and discriminatory laws," she said in a comment on HRW's website.

Contact the author at i.nechepurenko@imedia.ru

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.