It is unlikely that when Edward Snowden landed at Moscow's Sheremetyevo Airport a few weeks ago on a flight from Hong Kong and carrying tickets for connecting flights to Cuba and Ecuador, Russian authorities could have imagined what a headache they would have with this particular transit passenger.

It is highly unlikely that the Kremlin ever wanted him to stay in Moscow longer than a few hours during his layover in Sheremetyevo waiting for his connecting flight. But it is possible that once Snowden for some reason chose not to take his flight to Havana, the Federal Security Service wanted to speak with him. Simply out of curiosity, they might have wanted to find out what he knew, what type of person he was and what information he was carrying in his four laptop computers. If that was the case — and it would have been normal behavior for any intelligence service in the world — then the desire to satisfy that curiosity has come at a very high price.

Russian authorities probably wish they had slapped handcuffs on Snowden when he first landed at Sheremetyevo Airport and put him on the next flight to Havana. But, unfortunately, that chance is long gone.

In hindsight, Russian authorities probably wish they had slapped handcuffs on Snowden when he first landed at Sheremetyevo Airport and put him on the next flight to Havana. But, unfortunately, that chance is long gone. Instead, Snowden has gradually transformed his temporary refuge in Moscow into a podium for even more propaganda and self-promotion.

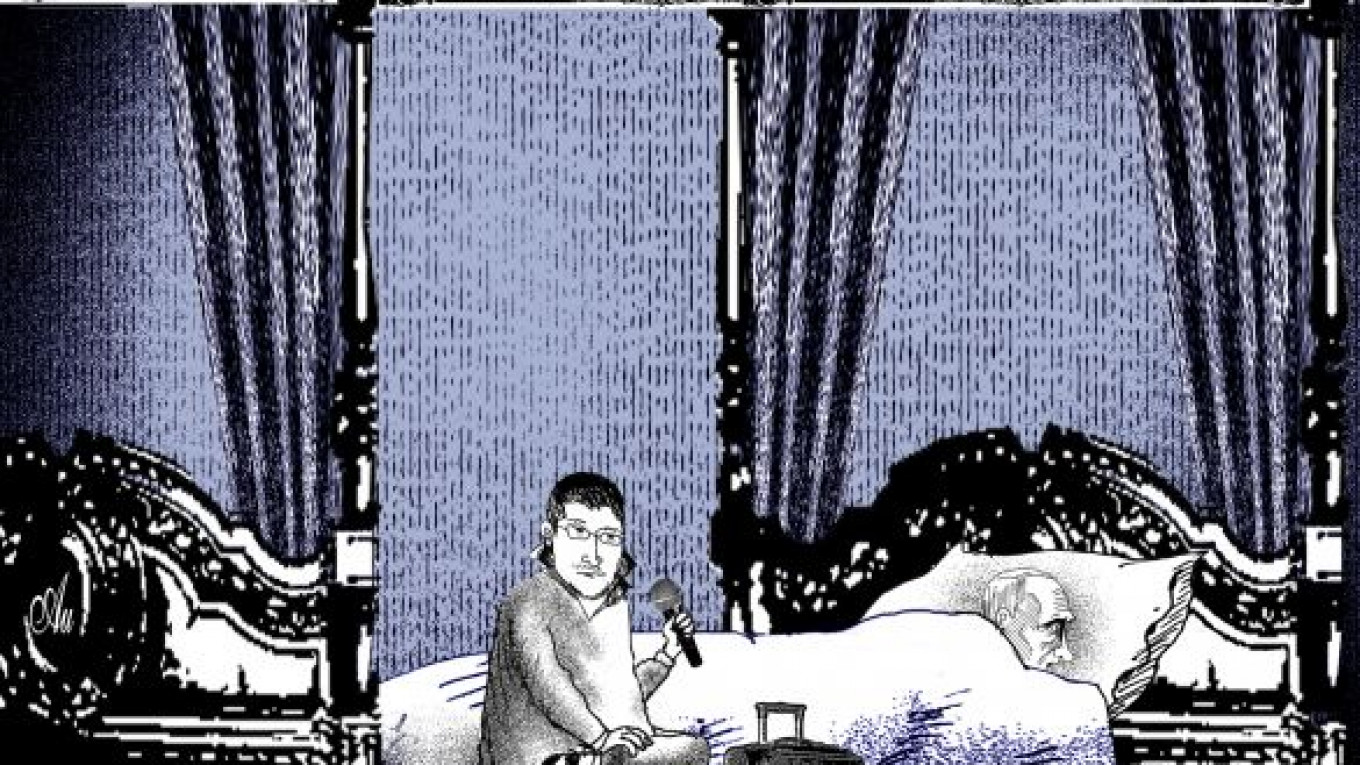

Washington publicly expressed irritation over Snowden's "news conference" Friday in Sheremetyevo Airport's transit zone, to which he invited Russian human rights activists, lawyers and government officials. U.S. authorities made it clear that they did not like the way Moscow engineered this PR show, reneging on its promise to remain neutral in the Snowden affair. Obviously, the meeting at the airport with human rights activists, politicians and public figures could hardly have been organized without permission from the senior leadership.

It is unlikely that President Vladimir Putin had originally wanted to grant Snowden political asylum. Snowden is in no way a hero in Putin's mind, and he probably considers him a traitor. It is no coincidence that Putin said Snowden could remain in Russia only if he did not harm the interests of "our U.S. partners."

Human rights activists are another category of people that Putin dislikes. But strictly speaking, Snowden could hardly be called a human rights activist. Both he and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange are members of the "Internet generation" that ostensibly fights for total freedom of information about everyone, everything and all the time. They become famous by divulging classified information that exposes "U.S. imperialism," despite offering no coherent platform, humanitarian vision or social alternatives of their own. It would make just as much sense to hang the label of "human rights activist" on the anarchistic, anti-globalization demonstrators who stage public rallies at every Group of Eight summit.

It is extremely difficult to understand the thinking and motivations of people such as Snowden, and that is why Russian authorities are so cautious in their dealings with him. Today he condemns the U.S, but what happens if tomorrow he takes a disliking to Russia and Putin's regime? It might initially be tempting to parade Snowden on various pro-Kremlin talk shows on state-controlled television, but once he becomes that famous, he might become even less manageable and predictable.

Complicating the whole situation is the fact that Snowden constantly flip-flops. On Friday, he essentially requested "temporary political asylum" in Russia, even though he had apparently refused it earlier. At the same time, Glenn Greenwald, a journalist with "The Guardian" and WikiLeaks sympathizer, said Snowden has an "informational time bomb" securely tucked away, and that if anything happens to him, he will divulge it and "destroy the United States in a single minute." That might be nothing more than an empty blackmail threat, but it would also be extremely risky for the authorities to completely dismiss it out of hand.

Snowden now claims that he is ready to abide by Putin's terms and has requested political asylum from Russia. The problem is that Snowden seems to have his own understanding of what constitutes "harm to U.S. interests." After all, even now he is convinced that he is acting in the interests of the American people by working against authoritarian U.S. intelligence agencies that themselves violate the public trust.

It might even be better to keep such an unpredictable leaker in Russia where the authorities could ensure that he did not leak any more information. But that would work only if Putin had some sort of secret agreement with U.S. President Barack Obama, who called Putin on Friday to discuss the Snowden affair, among other topics. Of course, if this agreement was made, it will never be made public — unless it is leaked.

To make matters worse, Obama cannot make his scheduled visit to Russia in September for the planned Moscow summit with Putin or the Group of 20 summit in St. Petersburg if Snowden is still in the country. In any case, the Snowden scandal will be only a temporary setback to U.S.-Russian relations. Like all scandals of this category, it is unlikely the two countries will quarrel for a long time over the incident. The most realistic option now is for Russia to provide some form of temporary asylum status for Snowden so he can soon make his promised visits to a South American country that has expressed support for him. For example, Venezuela has offered him permanent political asylum.

But this time, Russian authorities will have to make sure that Snowden boards the plane and leaves Russia — for good.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.