A senior U.S. lawmaker says he has been denied a Russian visa as a result of his vocal backing of the U.S. Magnitsky Act, which allows Washington to punish Russians implicated in human rights violations with a visa ban and asset freezes.

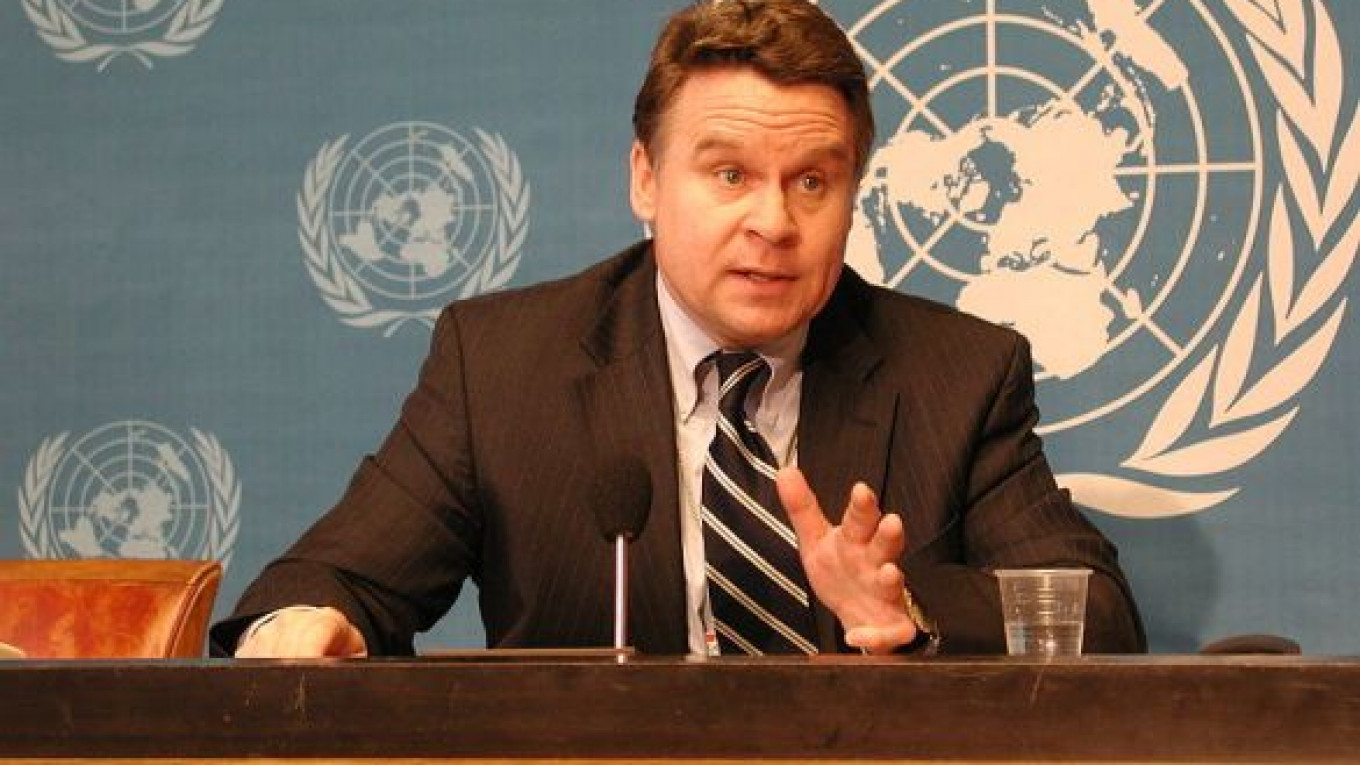

Chris Smith, a Republican congressman from New Jersey who has served in the House of Representatives since 1981, said it was the first time his visa application to Russia had been denied over many years of coming to the country.

"This is the first time [I've been denied]," Smith told Foreign Policy magazine on Wednesday. "I was shocked. During the worst days of the Soviet Union I went there repeatedly."

The visa denial is the latest sign of a cooling in U.S.-Russian relations following the U.S. Congress’ passage in November of the Magnitsky Act, which was fiercely opposed by Russian authorities, who have called it a form of meddling in the country's domestic affairs.

Russian lawmakers responded to the act by passing the so-called Dima Yakovlev law, which includes a reciprocal visa ban and asset freezes for alleged U.S. human rights violators as well as a ban on U.S. adoptions of Russian orphans.

Valery Garbuzov, deputy director of the Institute for U.S. and Canadian Studies in Moscow, said Smith's visa denial could be the first volley in an extended visa war that perhaps only the nations' top leaders can halt.

"President Obama cannot cancel the Magnitsky Act, so relations will have to be built on these premises," he said. "At the same time, the Russian response was excessive, which made the situation snowball."

Smith, one of the most vocal members in the U.S. Congress on human rights issues, said U.S. Ambassador Michael McFaul tried to intervene on his behalf to secure a visa but had no success.

The congressman said he also met with Russian Ambassador to Washington Sergei Kislyak, who said the decision to reject his visa application was made in Moscow, not at the Russian Embassy in Washington.

A Foreign Ministry official told The Moscow Times that the ministry never comments on individual visa decisions.

But Alexei Pushkov, head of the State Duma's International Affairs Committee, said the sponsors of the U.S. Magnitsky Act will not be allowed to travel to Russia, in accordance with the "spirit" of the Dima Yakovlev law.

"In every country, restrictions can be put in place for certain categories of people based on the spirit of existing legislation," Pushkov said by phone.

Smith was not among the Magnitsky Act's 15 official sponsors, who included House members Joseph Crowley, Charles Rangel and lead sponsor Dave Camp.

In January, Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov announced that Russia had compiled a so-called "Guantanamo list" of 71 U.S. nationals who were barred from entering Russia due to "human rights violations."

Rear Admiral Jeffrey Harbeson, a former commandant of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, was denied a Russian visa in December, apparently representing the first instance of Russia denying entry to a U.S. official after passage of the Magnitsky Act.

The last Russian parliamentarian to be denied a U.S. visa in recent memory was Duma Deputy and Soviet crooner Iosif Kobzon, whose application to visit the U.S. for a farewell concert tour was rejected in April.

Kobzon, who has been dubbed Russia's Frank Sinatra, has been denied visas to the United States since 1995, when his visa was revoked by American authorities for alleged mafia ties.

Members of the countries' business and nongovernmental communities have expressed concern that the cooling in relations could make it more difficult for regular citizens to obtain visas as well, although there have been no indications that such barriers will be established.

In September, a visa facilitation agreement came into force that allows Russian and U.S. citizens to get multiple-entry, three-year visas with reduced bureaucratic hurdles.

Of the measures stipulated by Russia's Dima Yakovlev law, also known as the anti-Magnitsky act, the Russian ban on U.S. adoptions has been arguably the biggest blow to Washington.

Smith said he was planning a trip to Moscow to discuss Russia's reaction to the Magnitsky Act and to help address Russia's concerns over the treatment of adopted Russian children in the U.S.

"I even have a resolution that highlights the fact that those 19 kids died," he told Foreign Policy, referring to the number of adopted Russian children Moscow says have died in the U.S. since 1996. That number excludes 3-year-old Maxim Kuzmin, whose death in Texas in January has set off a new firestorm of criticism by Russian officials.

"If somebody is responsible for this, they ought to pay a price," he said. "I was going over to talk about adoption and human trafficking. They have legitimate concerns that we have to meet."

Repeated requests for further comment from Smith went unanswered by press time Thursday.

The congressman has been a longtime critic of alleged human rights abuses in Russia. He was a co-author of the 2002 On Democracy in Russia Act and has repeatedly called for suspending Russia's membership in the G8, citing a lack of media freedom and human rights violations.

Smith said he intends to file another visa application.

Pushkov noted that the Obama administration is required by the Magnitsky Act to submit a list of Russian officials to go on the blacklist by mid-April, which could trigger another angry retort from Moscow.

But he called Obama a "hostage" of the law, which he said was pushed by conservatives in the U.S. Congress.

The legislation in fact had strong bipartisan support, but the White House reportedly did want to expand the law to make it apply to human rights violators from other countries, in part to appease the Kremlin by not singling out Russia.

"Obama genuinely wanted to repair relations, but the conservative part of the U.S. Congress decided to tie [his] hands with that law," Pushkov said.

Contact the author at i.nechepurenko@imedia.ru

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.