Twenty years ago today, I had the great honor of being editor of The Moscow Times when we launched the paper as Russia's first independent daily in English. Twenty years is a long time, and it is extremely gratifying to see that the paper has continued to exist and thrive over the years.

On the occasion of this anniversary, I'd like to share some memories of what it was like to start an independent paper in the Russia of those days – a Russia that had just been reborn as an independent country – and some thoughts about what it means to edit a newspaper in a place where the Kremlin continues to cast a long shadow, even if censorship has theoretically ceased to exist.

It was fall 1991 when Dutch publisher Derk Sauer phoned me in Paris to ask whether I'd consider moving to Moscow to edit a new English-language daily newspaper. At the time, Moscow was still the capital of a country called the Soviet Union. The Communist Party was in power in the Kremlin, and newspapers were censored, as they had been since the days of the tsars.

I had worked in Moscow as a correspondent for Reuters in the early years when Mikhail Gorbachev was leader, and knew Russia well enough to recognize Derk's proposal for what it was worth. The idea that upstart foreigners could come in and start an independent daily at first seemed just plain mad. But things were changing rapidly in the Soviet Union. As I thought it over, I began to view what Derk was proposing as one of those sounds-crazy-but-it-just-might-work ideas. And I couldn't resist the challenge.

We didn't know it yet, but when Derk brought me to Moscow just before Christmas that year to meet the team at the two publications he had already launched — Moscow Magazine, a monthly, and The Moscow Guardian, which came out twice weekly — the collapse of the mighty Soviet Union was only a few days away. On Christmas Day, Gorbachev stepped down, and Russia emerged as an independent country under the leadership of Boris Yeltsin. With the demise of the Communist Party, censorship began to fade.

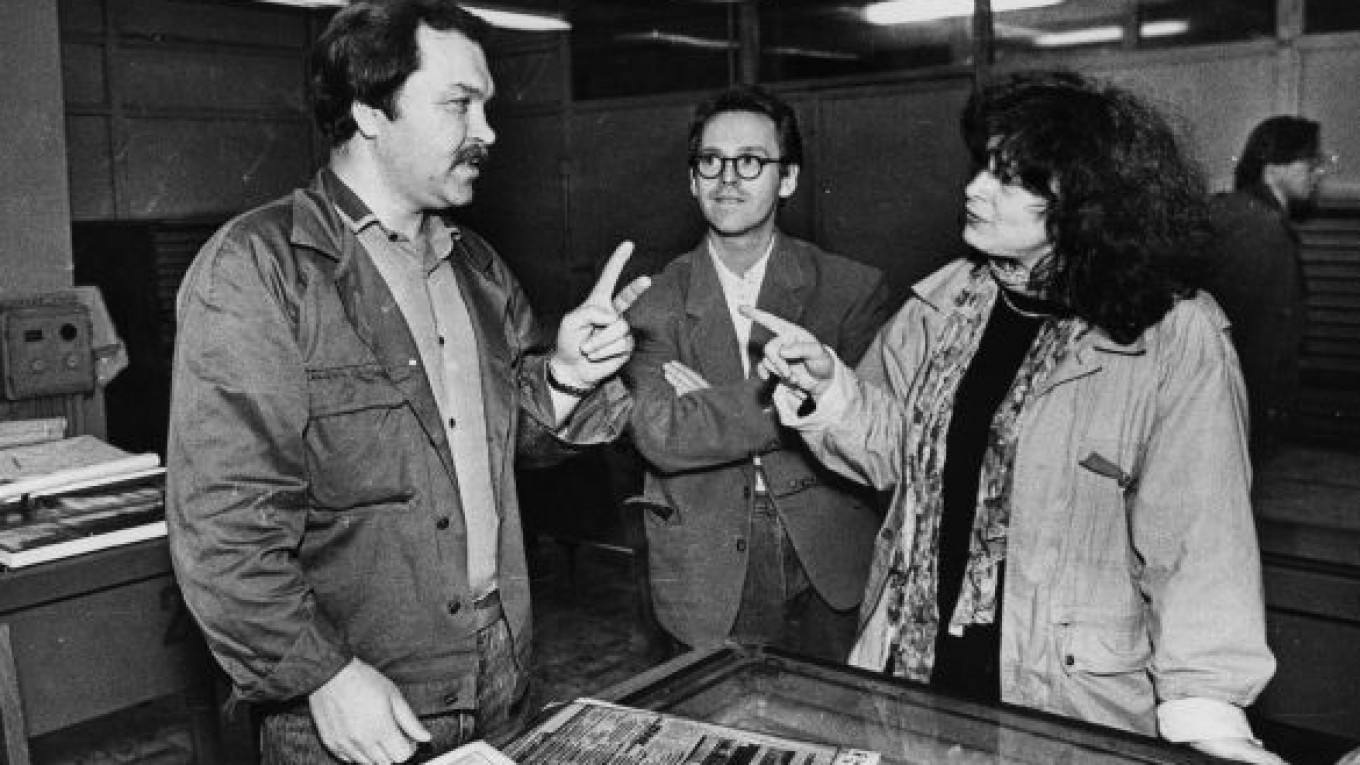

By the time I moved to Moscow in May 1992 to prepare to launch our new daily, The Moscow Guardian had been renamed The Moscow Times and Derk had moved his publishing operation into the Radisson Slavyanskaya Hotel. The paper was still coming out twice a week with its editor, Michael Hetzer, working out of one hotel room while, in the cubicle next door, I began the daunting task of hiring the editors and reporters with whom we would launch the daily in October. The challenge was to take the tabloid we already had and turn it into a world-class daily with international, Russian and city news, as well as pages for opinion, business, leisure and sports. All of this was done on a shoestring budget because we didn't yet know whether the paper could attract enough ads to pay our salaries.

I brought a young American newspaper designer, Eric Jones, from Paris, who got straight to work reconfiguring the paper. This involved everything from selecting new body type and headline fonts to figuring out where to put new featurettes like our going-out guide — called, with a wink to Lenin, "What Is to Be Done?" Within a very short time, the walls of my hotel cubicle were covered with Eric's dummy pages, which Derk would come by to view from time to time. Helping us was a talented Russian cartoonist, Igor Shein, who created some items for the paper that still exist today, notably the little sunny-day-cloudy-day weather boxes on page 2.

During this time, Michael Hetzer kept the paper coming out twice a week. He had a strong team of reporters and editors — among them Nanette van der Laan, David Filipov, Betsy McKay, Euan Craik and Anya Vakhrushcheva, as well as a brilliant photo editor, Galya Anichkina, and three fine photographers, Misha Metzel, Zhenya Stetsko and Volodya Filonov. These staffers would all segue to the daily in the fall. Meanwhile, Derk and his publishing partner, Annemarie van Gaal, built up the business side, which was responsible for making sure the paper got printed, distributed and promoted and for selling enough ads to keep the whole operation afloat.

Throughout the summer, new staffers arrived from the West and other would-be journalists came aboard from Moscow. They formed the nub of our initial team: Marc Champion, political editor; Steve Liesman, business editor; Karen Dukess, features editor; Jean MacKenzie, opinion page editor; and Shaker Khayatt, sports editor. Euan Craik became our chief copy editor, while Brenda Gray came aboard as production manager and Lindy Sinclair became our food and travel writer. We hired two interns, Chris Klein and Carey Scott, and a few more reporters. Marc Rice-Oxley, who had been due to join the British diplomatic service, walked into my office one day to chat and walked out as our crossword editor. It was a very young crowd — so young that toward the end of the summer, there was a collective identity crisis when the most senior editors turned 30.

But starting a daily didn't just mean hiring a staff. We had some logistical problems, chief among them the fact that the Internet didn't exist. We had to receive news agency copy over the wires, and we needed a satellite dish for this. I cannot remember how many hours I spent on the roof of the Slavyanskaya working on this problem, but eventually it got solved.

Once we had installed the news wires, we needed to read them. We hired a couple of copy assistants to tear dispatches off teleprinters and put them on clipboards for the editors. But to get the AP wire, which for some reason couldn't come in by satellite, Chris Klein had to walk about a kilometer to the AP office on Kutuzovsky Prospekt. He would come back bearing giant paper rolls of copy for editors to go through. The stories they chose then had to be typed into the system. But first we needed a system! Manfred Witteman, Derk's computer genius, achieved this with an Ethernet network, wiring our computers together through the walls of our hotel rooms to create a virtual newsroom.

Of course there were tensions because everything needed to be done in time for our launch in early October. The good news was that when it all got to be too much, we could refresh right in our offices. "That was the funniest thing about working out of a hotel," Eric Jones recalls. "Everybody had their own showers." Even better, there was a bar right downstairs in the Slavyanskaya. We repaired there increasingly often as September arrived and we began putting out dummy editions of the daily Moscow Times even as Michael Hetzer continued publishing the paper every Tuesday and Friday, with cross-pollination between the two versions and everyone working flat out. The news editor of the International Herald Tribune, Richard Berry, came to Moscow to lend his expertise during the launch period. And miraculously, by Oct. 1, we were ready.

When the first issue of Russia's first independent English-language daily came out the next morning — on Friday, Oct. 2, 1992 — no one could have imagined the impact The Moscow Times would have in the months and years ahead. In our first year, the editorial staff of 15 envisaged at the start had grown to 50, and the paper was being quoted both in Russia and the West as a primary source of news and opinion. We played an important role by giving space to Russian commentators who, despite relaxation of controls on press freedom, couldn't always find a Russian-language venue for their articles.

How important was brought home to me around the time of our first anniversary when anti-Yeltsin forces occupied the parliament and censorship was revived, meaning that Russian newspapers came out with large blank spaces on their front pages where articles critical of the authorities had been suppressed. The writers of those articles turned to us. Their articles, published the next day in English in The Moscow Times, were quickly picked up and beamed back in Russian by the BBC and other foreign radios, defeating the censors.

This independence was the strength of the paper — and still is 20 years on. It explains why The Moscow Times has remained an essential newspaper not just for Moscow's foreign community of diplomats, business people and journalists, but also for many independent-minded Russians. I regularly see the paper quoted in the world's most authoritative dailies, from The New York Times and The Guardian to Le Monde. It makes me proud to have been there right from the start, a feeling shared by many colleagues who were by my side.

As Chris Klein puts it: "The common thread is how honored we all feel to have been part of something that was new and important and that made a difference. We go into journalism to tell the truth and make a difference. To do so in such a challenging environment was especially meaningful for all of us."

The question for the next 20 years is whether the paper can retain this independence — a willingness to look at the news in Moscow and Russia and tell the truth, even if that truth is sometimes displeasing to the authorities. This is, of course, more problematic with a harder-line leadership in the Kremlin. For those of us who worked in Soviet times, it is difficult to read the news from Moscow these days without thinking back to those repressive years. And who knows how the Russia of President Vladimir Putin will evolve in the years ahead?

When I took the helm as founding editor-in-chief of The Moscow Times, I viewed my job's main challenge as helping readers understand a complex world. And that is still the challenge. It means striving for accuracy but also for fairness. It means organizing the pages in a way that makes sense of the confusing issues swirling around us. It means taking a clear editorial stand on the opinion pages, the one place where the editor may say how he or she views the news.

The next 20 years pose a challenge greater than the one I faced in October 1992, for Russia appears to be at a crossroads. Will it embrace democratic values or backslide into authoritarianism? Will it buttress freedom of expression or intensify the current trend toward censorship? Through all of this, will The Moscow Times succeed in telling the story, accurately, fairly and truthfully? Will it continue to make a difference?

I hope and trust that it will.

Meg Bortin served as editor-in-chief of The Moscow Times from 1992 to 1994. She is now living in Paris.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.