YAROSLAVL — In a city where boys want to be hockey players, and girls want to marry hockey players, it's not uncommon to see a young mother in high heels carrying her sleeping toddler to the rink in the middle of winter. Like everybody in this hockey town, she knows that it takes a long time to make a champion.

Yaroslavl has produced enough championship hockey players to be dubbed a "hockey factory." Players raised in Yaroslavl's elite hockey programs have gone on to play for the best teams in Russia, Europe and North America. They include Olympic gold medalists and world champions on all levels.

The city's home team, Lokomotiv, is packed with locals, so that when fans refer to the team as "our guys," they often mean it in more than one sense of the word. These are literally their brothers, fathers and friends, and their hard work and dedication to their craft sets an example that others aspire to.

It is difficult, therefore, to exaggerate the shock and grief that spread through this provincial city of 600,000 on Sept. 7 when Lokomotiv's charter plane crashed, killing 26 players, four coaches, and seven staff members — effectively the entire organization.

The team had been headed for their first match of the 2011-12 KHL regular season. The KHL is Russia's top league — the equivalent of the NHL in North America — and Lokomotiv's success in recent years had established it as a top contender for the Gagarin Cup, the league's top prize.

Thousands went into the streets and gathered outside Lokomotiv's arena, lingering well into the night to lay flowers, light candles and remember the dead. Among them were the victim's families, many having just identified their loved ones at the morgue.

THEY CAME LIKE PILGRIMS

The tragedy struck a chord with Russians beyond Yaroslavl, too. Yekaterina Sulayeva, 26, an accountant who lives in the Moscow region, hadn't heard of Lokomotiv at the time of the crash, but in the weeks after, she could think of little else.

"The more time went by, the harder it got. … I cried every day," she said recently at a Moscow restaurant. "I understood that if I didn't go to Yaroslavl, it wouldn't get any easier."

Through Lokomotiv's web site, she found three women from Moscow and the Moscow region who felt the same way, and together they organized a trip to Yaroslavl, four hours away.

Donations to the victims' families and condolences poured in from throughout the country. An old man with a cane traveled all the way from St. Petersburg — 600 kilometers away — to visit the players' final resting place.

THE HOCKEY FACTORY

School No. 9 is an ordinary primary school that has a special program for hockey players. Combined with two dedicated hockey academies, it forms the foundry of the city's hockey development program. On Sept. 7, School No. 9 lost 10 alumni, including team captain Ivan Tkachenko, 33, and Maxim Shuvalov, 18, who was traveling with the team for the first time. Their photographs now hang on a wall next to those of graduates who died fighting in Afghanistan and Chechnya.

A list of 12 school rules hangs on the wall by the entrance. No. 5 is: "Be physically active, play sports and maintain personal hygiene and cleanliness at school, home and in public."

Longtime headmaster Sergei Shevchenko is proud that the young hockey players who come to his school get a general education, as well as plenty of hours on the ice. Shevchenko teaches history — he has a particular fondness for the Napoleonic period — and he remembers the hockey players well and kept in touch with many of them. He also attends every home game to watch them play.

Hockey players, he said, tended to be confident and strong-willed from an early age.

"Vanya [Tkachenko] was a smart, attentive kid. He always got A's in history," he said, flipping through a photo album on his desk. He pointed to a black-and-white photograph of a bright-eyed boy with neatly cropped hair, sitting at the front of the class, resting his head on his folded arms. With the flip of a page, the boy becomes a bleary-eyed teenager in a slim suit with shoulder-length hair, looking more like a grunge rocker than the boy who would become Lokomotiv's most-beloved hockey player.

THE HEART OF THE TEAM

Tkachenko played his final 10 seasons with Lokomotiv Yaroslavl, earning the respect of fans and teammates with his heart and hustle. Off the ice, he had a way of making people feel at ease. In April, he and his best friend, Yevgeny Panin, opened a bar called "Rocks," which they conceived of as a laid-back hangout for friends and sports fans.

"He went to court three times to get this bar built," Panin said, proudly surveying the interior, which he said was inspired by the lattice iron work on the Brooklyn Bridge. Vanya applied the same effort and attention to detail to the bar that he did to hockey. "I'd e-mail him photos of the paint color, and he'd reply from whichever faraway city he was in. 'Too bright' or 'too dull,' he'd say. We must have painted the walls ten times."

The room is filled with rock 'n' roll memorabilia that Vanya bought on eBay, including a photo of Freddie Mercury and a replica of the Abbey Road sign. Vanya's No. 17 jersey hangs in a frame by the entrance beside the plastic card that officially made him a member of the bar he founded. It's melted on the corners, but the raised text is still legible: Member No. 1.

Tkachenko was member No. 1 in the eyes of many here: a strong leader, a honest man, a loving father — he left behind a pregnant wife and two young daughters — and a helping hand in the community. When school No. 9 marked its 50th anniversary, he volunteered to organize and sponsor the celebration, and stopped by often enough for the boys to recognize his car.

It was telling that when Panin and his wife asked their young daughter to name their forthcoming child, she said, "Name him Ivan, so that he'll be like Uncle Vanya."

After his death, it emerged that over the past 4 1/2 years, Tkachenko had secretly donated almost 10 million rubles ($320,000) to children suffering from cancer. He made his final donation, 500,000 rubles ($16,000), the day before he .

FINAL RESTING PLACE

"Given how rough they were on the ice, you would never guess how sweet they were in real life," said Yelena Sidorova, standing over the grave of her son Yevgeny, 44 — a trainer with the team — on an overcast December afternoon.

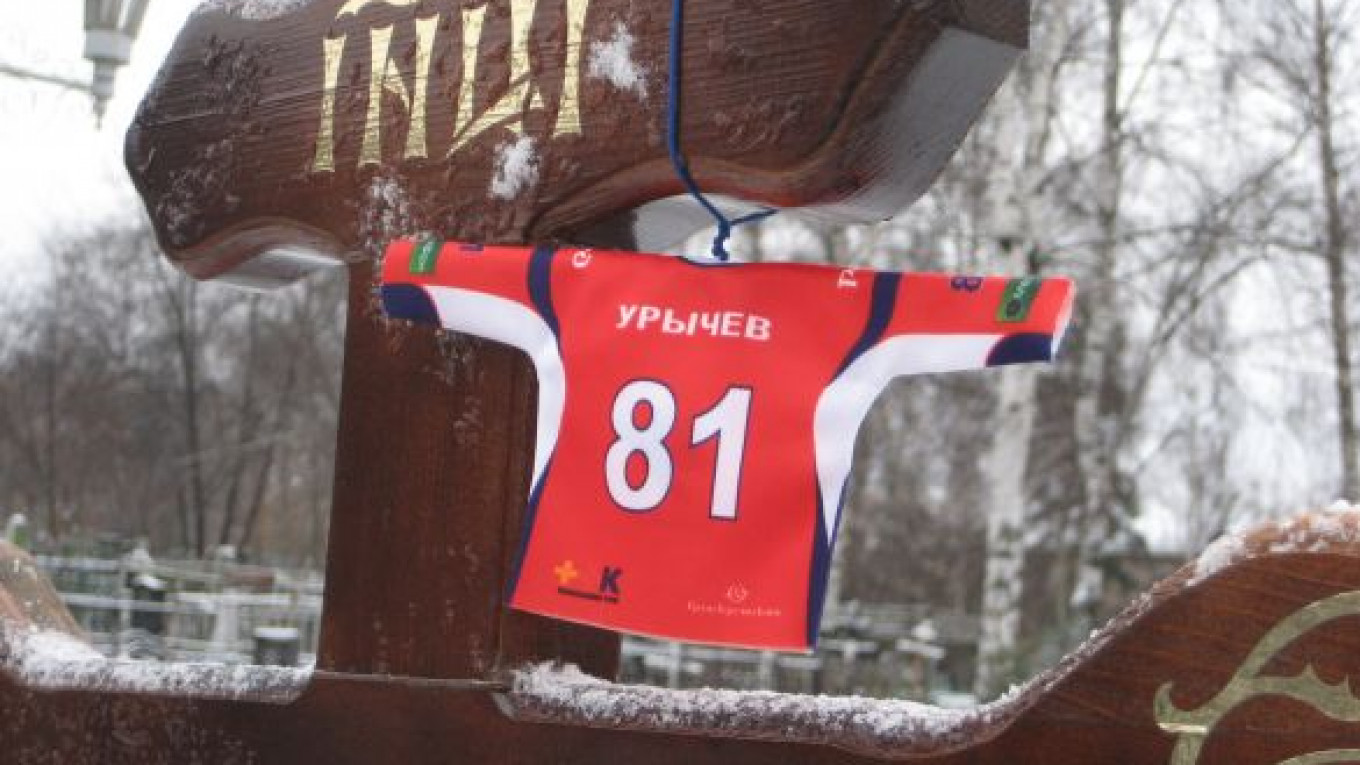

Fourteen Lokomotiv players and staff are buried in two rows near the entrance to the Leontyevskoye Cemetery. In the fall, the raised graves were stacked high with natural flowers — carnations and roses — but those have since been replaced with artificial ones that can withstand the cold.

Yelena's psychologist says she should limit her cemetery visits, but she says she can't help visiting every day.

"The sun stopped shining for me that day. I lost my reason to live," she said. "The only time I feel OK is when I'm near him."

She walks carefully between the graves, stopping in front of each to say a kind word. "They were all good. Every one of them."

"The big heart represents his wife; the small one — their daughter," she says, pointing to two hearts made of woven flowers on the grave of defenseman Mikhail Balandin, 31. "He never said a harsh word to her in almost 12 years of marriage."

Despite subzero temperatures, Yelena is far from the only visitor at the cemetery. A pretty, blonde girl stands in front of the grave of left-winger Alexander Vasyunov, 23 — who spent last season with the New Jersey Devils — crying softly.

"Tanya, say something about Lesha," Yelena asks her.

"I can't," she says.

"What was he like?" Yelena asks.

Tanya wipes her eyes with the cuff of her jacket.

"He was the best."

Left-winger Andrei Kiryukin, 24, was one of five victims engaged to be married.

"He proposed to his girlfriend in Venice. We had such high hopes. Now all we have are the candles on his grave," his mother, Tatyana Kiryukina, said. It was Tatyana who introduced herself to Yelena Sulaeva and her friends in the cemetery in September and invited them to her house.

Andrei Kiryukin's hockey bag is still lying in the hallway of Tatyana's small apartment, a short bus ride from the cemetery.

"I'll never put it away. As long as it's here, he's here," his mother said. She read a poem — one of the many she's written about her son — then treats her visitors to reheated moose meat and caviar that Andrei brought back from a trip to the Far East.

Andrei was 16 when his father, Anatoly, a former professional football player — died of a heart attack before his very eyes, his mother recalls.

"He said to me, 'Now I'll take care of you.' And he did — he called or wrote every single day to let me know where he was."

SHATTERED DREAMS

Like many young couples today, Maxim Shuvalov and Olga Sokolova's courtship took place over text messages, e-mails, phone calls and social networks. Given Maxim's rigorous travel schedule, this was often the only way they could reach each other.

Maxim used to draw pictures on her profile on the social network Vkontakte. On Sept. 4, he drew "Darling, I've arrived," in red script against a purple background with hearts. On Aug. 19, he wrote, "Good morning, love," with a shining yellow son.

Shuvalov, 18, was the youngest person on the plane that day. He had recently been called up from Lokomotiv's farm team for the first regular season game in Minsk. It was a major professional step and the validation of a lifetime of rigorous training.

Olga, 18, had been with him for two years, watching him endure every hit, consoling him when he felt he wasn't doing well enough, which was most of the time. She marked on her calendar the days when he would be in town, and looked forward to moving to Yaroslavl from nearby Rybinsk to attend university and be with him.

She received her last text message from him at 3:58 p.m. on the afternoon of Sept. 7., less than 10 minutes before the crash. It was heartbreakingly routine, though in hindsight, Olga says she knew something terrible was about to happen. "My darling. We're taking off. I'll write you when we land."

Since the tragedy, Olga has become close friends with another young woman, Viktoria Kashikhina, who's fiance, Pavel Snurnitsyn, 19, had also just been called up.

"Pasha was so excited," she recalls, adding that she had daydreams of him scoring a goal in Minsk.

As she speaks, Viktoria reaches into her purse and pulls out a black smart phone. "Other than the smell, you'd never know it had been through a plane crash," she said. The smell of kerosene is strong and unmistakable. "It still takes photographs," she said.

"I still call Maxim every morning," Olga said. "I can't reach him anymore, of course, but I still feel the need to try. … It feels like they've just flown far away, and we're waiting for them to come home."

FEAR, LOATHING AND RESURRECTION

Forty-four were killed when the team's chartered Yak-42 airplane slammed into the banks of the Tunoshonka River — a small tributary of the Volga — breaking apart and bursting into flames. Some burned to death. Some were decapitated. Some drowned. Only one, mechanic Alexander Sizov, lived.

The Interstate Aviation Commission named pilot error as the official cause of the crash. The commission concluded that one or both of the pilots — possibly under the influence of a sedative — pressed on the breaks as the plane was trying to build speed for takeoff. As a result, they claim, the plane did not gather sufficient speed and consequently stalled and crashed mere seconds after takeoff.

But Yaroslavl is uniformly skeptical of this explanation, and alternate theories abound. A group of experts hired by some victims' relatives, citing evidence that the plane became uncontrollable after takeoff, claimed that mechanical failure was to blame. Some, like Yelena Balandina, suspect more sinister culprits.

"Our boys were killed," she said, adding that she'd spoken with eyewitnesses who claim to have seen two explosions tear the plane apart in mid-air.

The match in Minsk had initially been scheduled for Sept. 6 in Yaroslavl, but the Yaroslavl International Economic forum — which brought President Dmitry Medvedev, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and other top officials to the area — caused it to be moved to Minsk, spawning unconfirmed rumors that the flight was rushed into flight.

"Where is the video recording of the flight?" asked Ivan Tkachenko's brother, Sergei. "We have 10 cameras in this tiny bar. I don't believe they didn't videotape outgoing flights."

Relatives may be skeptical and frustrated, but they're equally afraid of speaking out against the government that many accuse of incompetence or worse, a cover-up. A small group of victims' relatives has hired hotshot Moscow lawyer Igor Trunov to challenge the official version, but the vast majority simmer in private and in interviews with the media.

"We don't know how to get the truth," Sergei Tkachenko said.

The victim's relatives are legally entitled to insurance payments from three different insurers, and have been promised payouts from Lokomotiv's charitable fund and local authorities.

Yelena Balandina said she'd received 550,000 rubles ($17,600) from the city and one of the insurance companies. Further payments in the millions of rubles are expected in the near future, although neither the team nor insurer Leksgarant were willing to give a timetable when contacted.

Lokomotiv spokesman Alexander Sakhanov said the club was tired of talking about the Yak-42 crash.

"We're in a new period. We're preparing a new team," he said.

Indeed, in a meeting presided over by President Dmitry Medvedev held the day after the crash, officials from Lokomotiv, the KHL and the Ministry of Sport, Tourism and Youth Policy, agreed on a plan that would see Lokomotiv return to the KHL next season.

The team's commercial director, Yevgeny Chuyev, put it bluntly. "We'll be back. There's no doubt about it."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.