Most Russians still have negative feelings about the liberal reforms of the 1990s and are more positively disposed toward the 2000s. But at the same time, acts of aggression and nationalistic sentiment are growing throughout society. There has been a significant increase in the number of people wanting to work abroad temporarily or to leave Russia altogether.

Russians views toward their country are filled with contradictions. They tend to recognize the value of democracy but are pessimistic about its prospects. They support the country’s chosen path but do not anticipate any significant success in the near future. They value freedom and private initiative but support a range of paternalistic notions including the need for the state to control the economy.

These findings were confirmed in a major study by the Russian Academy of Science’s Sociology Institute that was conducted this spring under the direction of Mikhail Gorshkov in cooperation with the German F. Ebert Foundation. The report, “20 Years of Reform Through Russian Eyes,” analyzes the dynamics of Russian public opinion during the two decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The number of people with a negative attitude toward the reforms of the 1990s, although decreasing somewhat, remained high, shifting from 43 percent to 34 percent. But 69 percent of Russians felt that the reformers themselves did not intend to build democracy and a market economy, but wanted to seize power and to redistribute public assets among themselves.

Only 6 percent of respondents felt that the reforms were conducted properly. Russians listed only four positive outcomes from the reforms of the 1990s: an abundance of consumer goods, the freedom to travel abroad, an ability to earn unlimited money and an end of religious repression along with the strengthening of religion’s role in society.

Of the two post-Soviet decades, public opinion clearly favors the 2000s over the 1990s. Most of those questioned said the 2000s provide better opportunities to improve their standard of living, engage in business, develop professionally and even to participate in the country’s social and political life.

But having better opportunities does not necessarily mean they were successful in achieving those goals. The decade under Vladimir Putin only compares favorably to the 1990s, but on its own the 2000s are not considered a period of progress. Public opinion gave unqualified high marks to the current regime on only two points — strengthening Russia’s position in the world and restoring order at home. The authorities earned far lower ratings for their ability to improve the economy and the general standard of living, for defending democracy and political freedoms and for resolving the situation in the North Caucasus.

The sharp change in attitudes in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other major cities is another important development. In Moscow, 61 percent of the population is ready to “shoot” those responsible for their problems. Only two years ago, 69 percent of the people of Moscow and St. Petersburg gave an overall positive assessment of the situation in the country. Today, that number has fallen precipitously to 22 percent.

Two problems have worsened from the 1990s to the 2000s: the lack of a social safety net for those who are sick, old, unemployed or disabled and the lack of protection from violence.

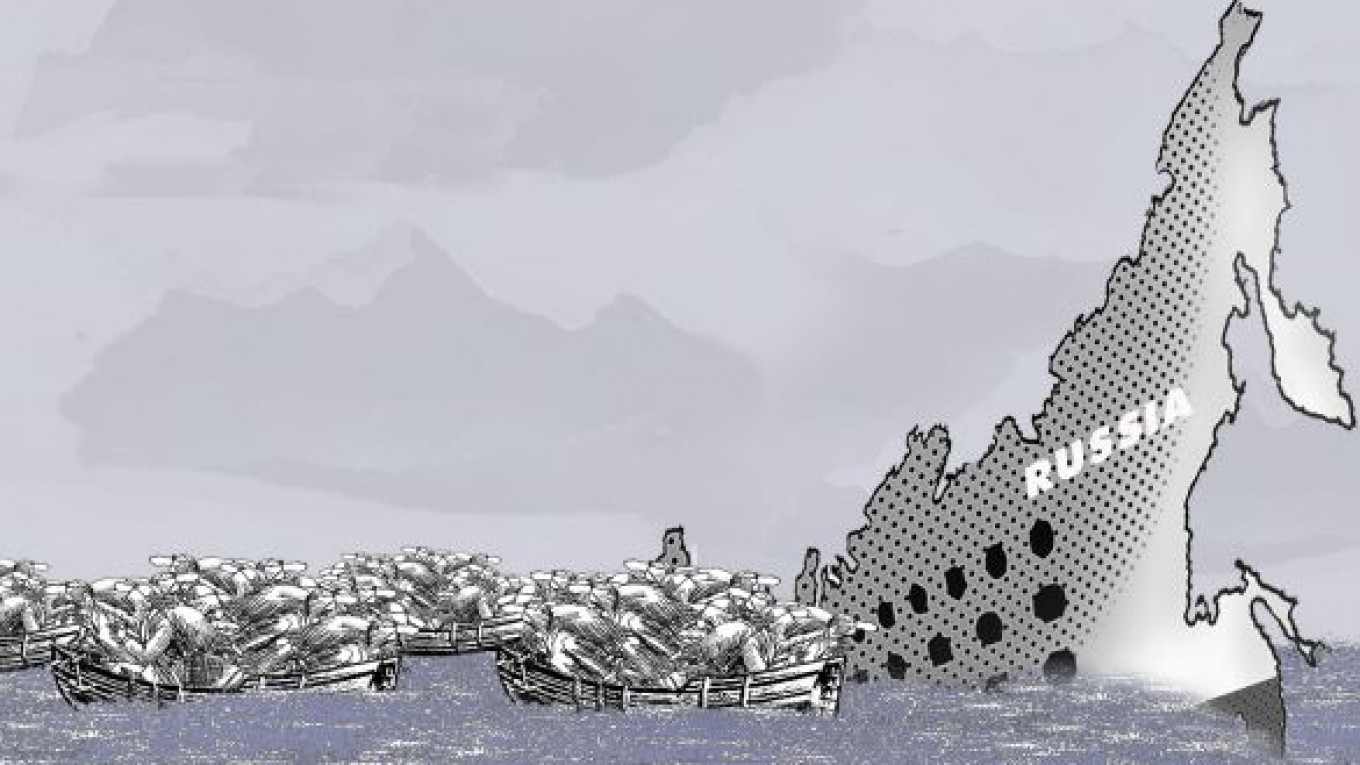

The number of people wanting to leave Russia to study abroad, work or emigrate has risen steadily. Today, fewer than half of all respondents say they would never want to leave the country, while 13 percent would like to leave Russia forever — 150 percent more than felt that way 10 years ago. One in every five Russians under 30 years of age would like to emigrate.

Only 29 percent of those polled consider Russia to be a democratic country, while 48 percent believe it is not. What’s more, only 23 percent of people in the two capitals view Russia as a democracy – the lowest number in the country. The study showed that 71 percent of Russians believe that ordinary people have no influence over the affairs of the country. The result is a rapid loss of interest and participation in politics. At the same time, however, the number of people who believe that rallies, demonstrations and strikes are effective has doubled in the last 10 years.

And although a 57 percent majority of respondents favor stability, those wanting fast and radical change have grown to 42 percent and 54 percent among youth. The rapidly changing mood among the most progressive segments of the population — people living in large cities and youth — suggest that they will be more demanding of political change.

The future of Russia could very well depend on whether the Kremlin treats these demands seriously.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is a co-founder of the opposition Party of People’s Freedom.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.