The latest increase in electricity tariffs in Russia, effective Jan. 1, were instituted not only to keep pace with inflation, but in part to cover the additional costs related to the introduction of the regulator asset base tariff system for use of the distribution grids. Consumers are paying more for their electricity, and they are entitled to know why.

Between one-quarter and one-third of electricity tariffs represent the cost of constructing, maintaining and operating the low-voltage distribution grids. The essence of the regular asset base tariff system is that regulators have approved tariffs in advance for a five-year period and, for the first time in Russia, tariffs include an element of net profit. The level of allowed profit has been calculated as a percentage financial return on a figure the Federal Tariffs Service has approved as a fair value for the grid assets — that is, the regular asset base.

Previously the regulator allowed the companies to add a few percentage points each year to the operating cost element in tariffs. As a result of years of almost unconstrained cost growth, Russian consumers now pay about twice as much for grid operating costs than do consumers in Western Europe. Under the new regular asset base system, each year the federal regulator will, instead, decrease the amount of operating costs distribution companies are allowed to include in tariffs. Moreover, the new system will allow the companies to retain any cost savings they achieve beyond the annual decreases stipulated by the regulator. Like profit, the additional cost savings can then be ploughed back to fund grid improvements.

As the distribution companies develop under the new system, Russian and international banks will perceive them as stable, low-risk customers and will be lining up to provide credits at low rates of interest. These loans, too, will be used to fund grid renewal. Thus, distribution companies will be able to access in financial markets the trillions of rubles they need to upgrade the grids. For all this, consumers will pay slightly higher tariffs in the short term, but will soon reap the benefits in the form of safe, reliable electricity supplies at reasonable prices.

If this picture seems too rosy, it is one that has been reproduced in a host of countries over the past 20 years or so. This is a shining example for the management of national infrastructure that, as Prime Minster Vladimir Putin has said, can be copied so that Russia gets both a safe, efficient electricity industry, as well as world-class roads, bridges, ports, railways and airports.

At the same time, regular asset base tariffs are unproven and unfamiliar in Russia. Distribution company managers have to put their faith in the willingness and ability of financial markets to deliver the billions of dollars needed every year to keep the grids working. Managers need to create the kind of efficient, transparent and profitable public shareholder companies of which there are few, if any, in Russia today.

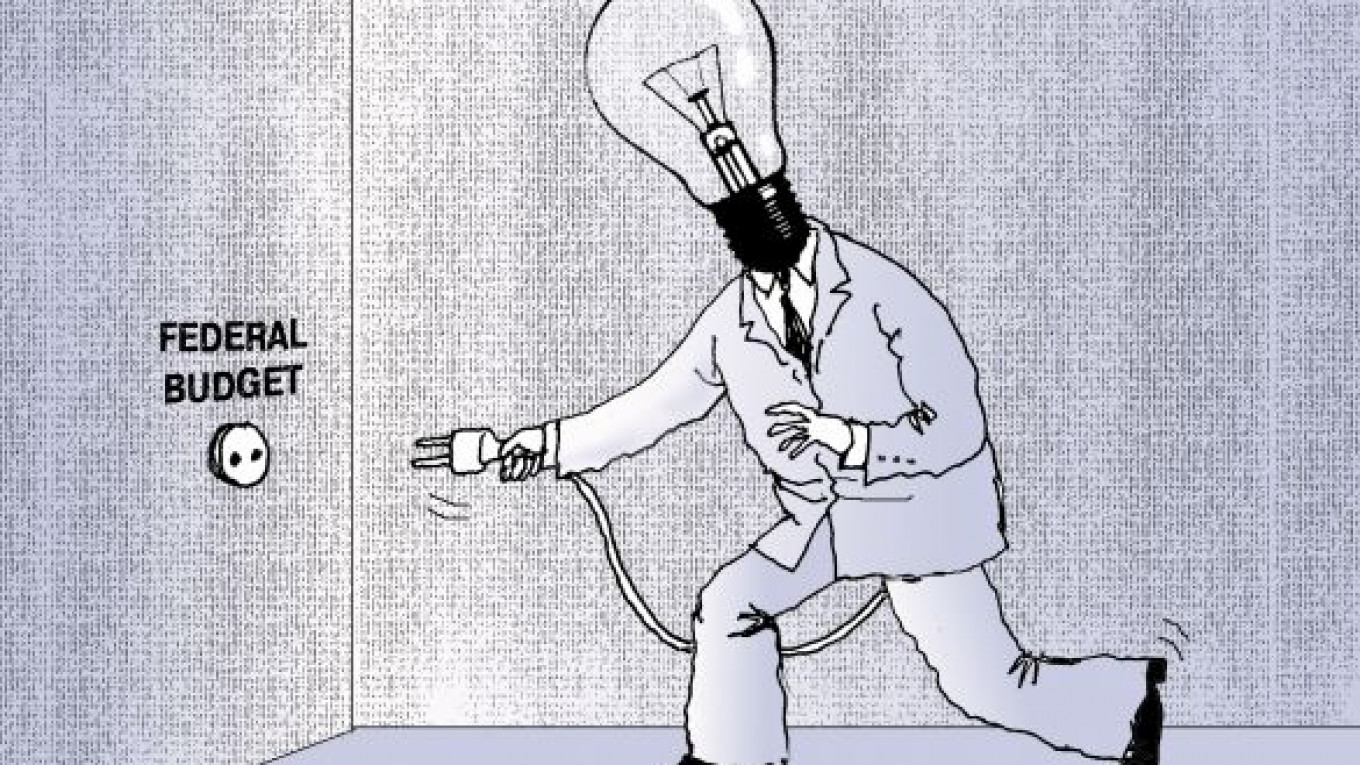

Thus, it is not surprising that sector managers have sought a cushion in the form of a request to Putin for 800 billion rubles ($26.8 billion) to be earmarked from the state budget to fund grid investment. Unfortunately, this seemingly innocuous request represents a very big step in the wrong direction — a step from which there is no obvious way back.

Were the proposal to be implemented, the state would receive distribution company shares in return for its 800 billion rubles, thereby increasing state ownership in a sector where the government’s commitment to privatization has been welcomed by investors and applauded by international experts. It would be a direct contradiction, too, of the frequently stated view of senior government ministers, including Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, that the budget can no longer afford to pour money into inefficient state companies.

Gone, too, would be any thought of distribution company managers earning bonuses in return for squeezing down their companies’ costs. How could this novel incentive scheme compete with the distraction created by 800 billion rubles of budget funds flowing down through the sector, without giving shareholders or consumers the ability to question how the cash is spent? Far from becoming model public shareholder companies, the distribution companies would become the kind of state enterprise of which Russia already has more than enough, providing rich pickings for managers and bureaucrats and mediocre service for consumers.

Russia is at a watershed. On one side, the country faces the unfamiliar territory of international financial markets, managers who receive financial incentives for reducing costs and the challenge of having to adapt to new ways. But these ways lead to efficiency, integration with the global economy and development of the national infrastructure Russia needs to support President Dmitry Medvedev’s vision of a productive society and a modern, diversified economy. On the other side of the watershed lies more comfortable territory — handouts from the state budget, which are beguiling in its familiarity and promise of stability. But this is the stability of decline that leads to more social imbalances to the unreliable, unsafe infrastructure that is usually associated with failing states.

The distribution companies do not need budget funds, and the government should tell them so.

Derek Weaving is head of utilities research at Renaissance Capital. He contributed this comment to Vedomosti in a private capacity, and the views expressed are entirely his own.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.