Exhibits Grapple with Gorbachev, Yeltsin’s Legacies

This spring, the Moscow House of Photography commemorates the 80th birthdays of Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s last head of state, and Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first president, with a pair of exhibits on the two leaders’ lives and legacies. The rich trove of contemporary photographs, videos and artwork they display highlights Russians’ conflicting feelings over the tumultuous changes of the 1980s and ’90s — and the leaders responsible for them. (photo gallery)

“Mikhail Gorbachev. Perestroika,” which is housed in a mammoth space in the Manezh exhibition hall near the Kremlin, offers a spirited defense of the leader and his revolutionary economic and social reforms.

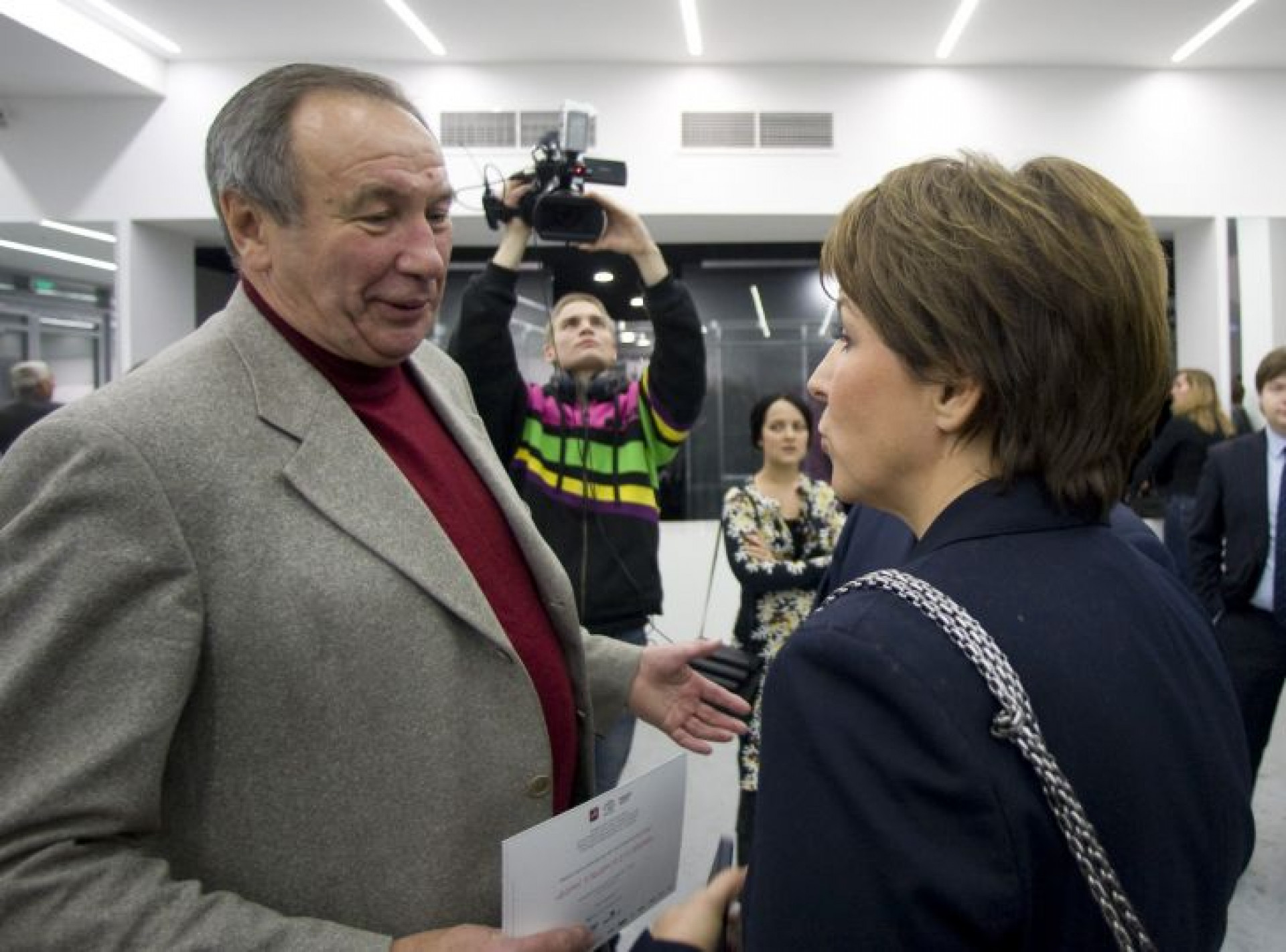

The exhibit’s opening featured Gorbachev, his daughter Irina and granddaughter Ksenia, and public luminaries including Mosfilm director Karen Shakhnazarov and musician Andrei Makarevich.

Gorbachev expressed the exhilaration he felt during perestroika’s early stages, as Soviet citizens were granted the right to vote in free elections and travel abroad.

“Although my entire life I was among the people, and really felt like one of the people, nevertheless I was amazed by how the people met this freedom,” he said.

Speakers at the opening emphasized the importance of reckoning with perestroika. “This was a time when our country was given a lot of chances,” said Irina Virganskaya, Gorbachev’s daughter and vice president of the Gorbachev Foundation. “We should all think about how we used them.”

“We don’t need the pessimistic optimism that says ‘time will judge,’” said Olga Sviblova, founder and director of the Moscow House of Photography. “We were there during that time, we know it, and we’ll judge it.”

U.S. ambassador John Beyrle recounted how he first met Gorbachev in 1985, during his first meeting with then-Vice President George H.W. Bush. “[Bush] came out of the meeting and told us he’d met … ‘a very, very different Soviet leader.’”

“We had a lot of hopes for Mikhail Gorbachev, and he didn’t let us down.”

While Gorbachev has long enjoyed a heroic status abroad, unpopularity continues to plague him in Russia. At the opening, he told a joke from the time of his anti-alcohol campaign in which a man frustrated by a two-kilometer line to buy vodka decides to go kill Gorbachev, only to discover that “the line there was even longer.”

The exhibit’s enclosing wall offers a roughly chronological account of the era, beginning with the heady early moments of perestroika, such as the exuberant youth festivals in 1985, and eventually building to the ‘91 coup and Gorbachev’s replacement by Yeltsin. Official portraits feature Gorbachev in moments of official triumph, such as a 1987 meeting with Ronald Reagan; family photos offer more personal glimpses of Gorbachev’s and wife Raisa’s youth.

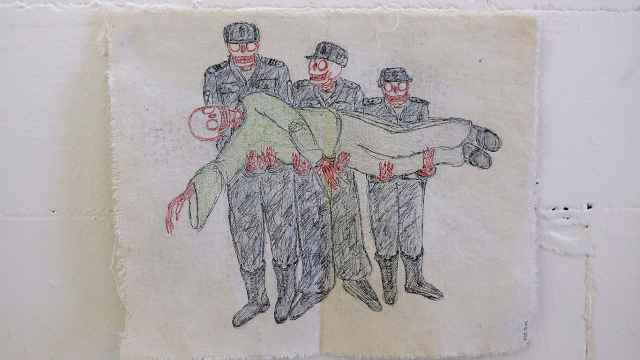

The exhibit’s photos highlight the dueling forces of stagnation and change that shaped the period: chickens pecking in a communal apartment hang yards away from teenage punks and avant-garde fashion shots.

Perestroika-era broadcasts, newspapers and films, as well as installations by Yuri Avvakumov and Pavel Kassin, accompany the photographs.

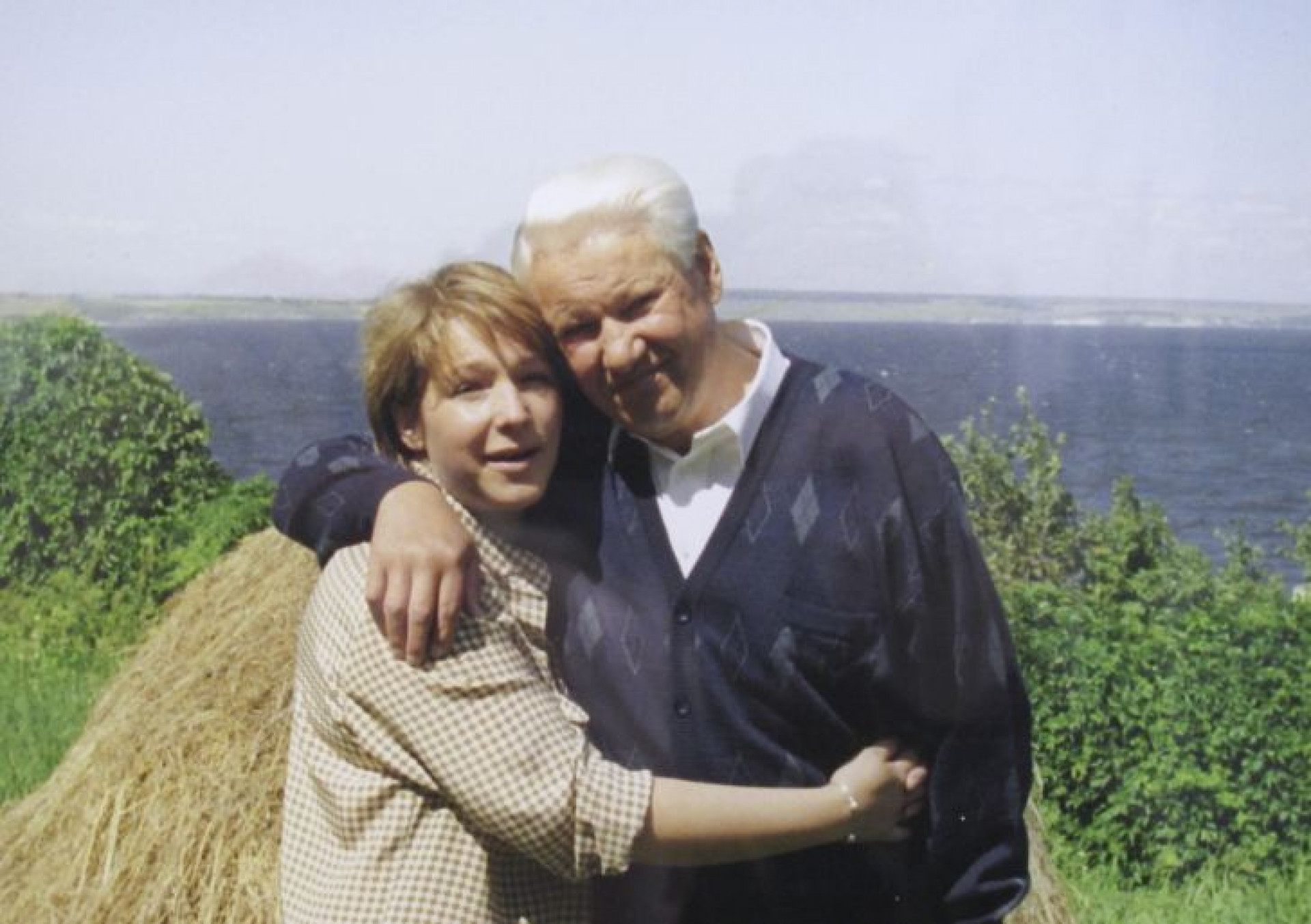

“Yeltsin and His Time” offers a look at the first Russian president that is smaller but equally complex. Shots of Yeltsin’s achievements in office ring the room; in the center, displays are plastered with images of the political, military and social conflicts of the ’90s, including the war in Chechnya and the poverty wrought by hyperinflation.

Rather than focusing on praising his era’s achievements, as at the perestroika opening, Yeltsin’s friends and colleagues paid most of their attention to the former president’s personality.

“A lot has been said about him, but there should be a book about Yeltsin as a person,” said his former tennis trainer, Shamil Tarpischev. “It was impossible not to fall in love with him … he had a natural humor.”

In her remarks, Yeltsin’s widow, Naina Yeltsina, emphasized how “bright and beautiful” a man Yeltsin was, recalling how he would get excited “like a child” when receiving presents on his birthday.

The exhibits kick off a series of celebrations across Russia and Europe in honor of Gorbachev and Yeltsin’s birthdays.

On Feb. 1, President Dmitry Medvedev will attend the unveiling of a 3-meter tall statue of Yeltsin in Yekaterinburg. Other planned Yeltsin birthday celebrations include a memorial concert at the Bolshoi and a tennis tournament in Kazan.

At the opening in his honor, Gorbachev addressed the controversy that, unlike Yeltsin, his primary birthday celebration will take place abroad, in a star-studded gala concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall. He pointed out that the gala’s proceeds will go to charity, and that he will celebrate his actual birthday, which is on March 2, in Russia.

In comparing the two exhibits, House of Photography deputy director Sergei Borosovsky said he found “Boris Yeltsin and His Time” more successful. The perestroika exhibition “came out as more of an art object and isn’t so much about Gorbachev” he said. But the free press whose work is the heart of the Yeltsin exhibit shows “all the pluses and minuses” of the ’90s, he said.

“Everything the country lived through, we tried to show,” Borosovsky said.

In examining each man separately, the exhibits skirt the topic of Gorbachev and Yeltsin’s complicated relationship. However, Gorbachev claims not to harbor a grudge toward his old ally-turned-opponent, who defended him during the attempted 1991 coup but then orchestrated his removal from power. When a reporter asked him whether he still resented Yeltsin, he shrugged.

“What’s resentment in politics?” he said.

“Mikhail Gorbachev. Perestroika,” runs through March 8 at Manezh, 1 Manezh Square. Metro Biblioteka Imeni Lenina. “Boris Yeltsin and His Time” is on show at the Moscow House of Photography, through March 13. 16 Ulitsa Ostozhenka. Metro Kropotkinskaya. Tel. 637-1100, www.mdf.ru. To view our photo gallery of the premieres, click here.