The latest meeting of the anti-corruption council on Jan. 13 chaired by President Dmitry Medvedev was so unremarkable that it went practically unnoticed by ordinary Russians.

Meanwhile, analysts and the media have focused their discussion of that meeting on Medvedev’s idea of introducing fines for those convicted of bribery — as well as middlemen who profit from these schemes — equal to 100 times the amount of the bribe.

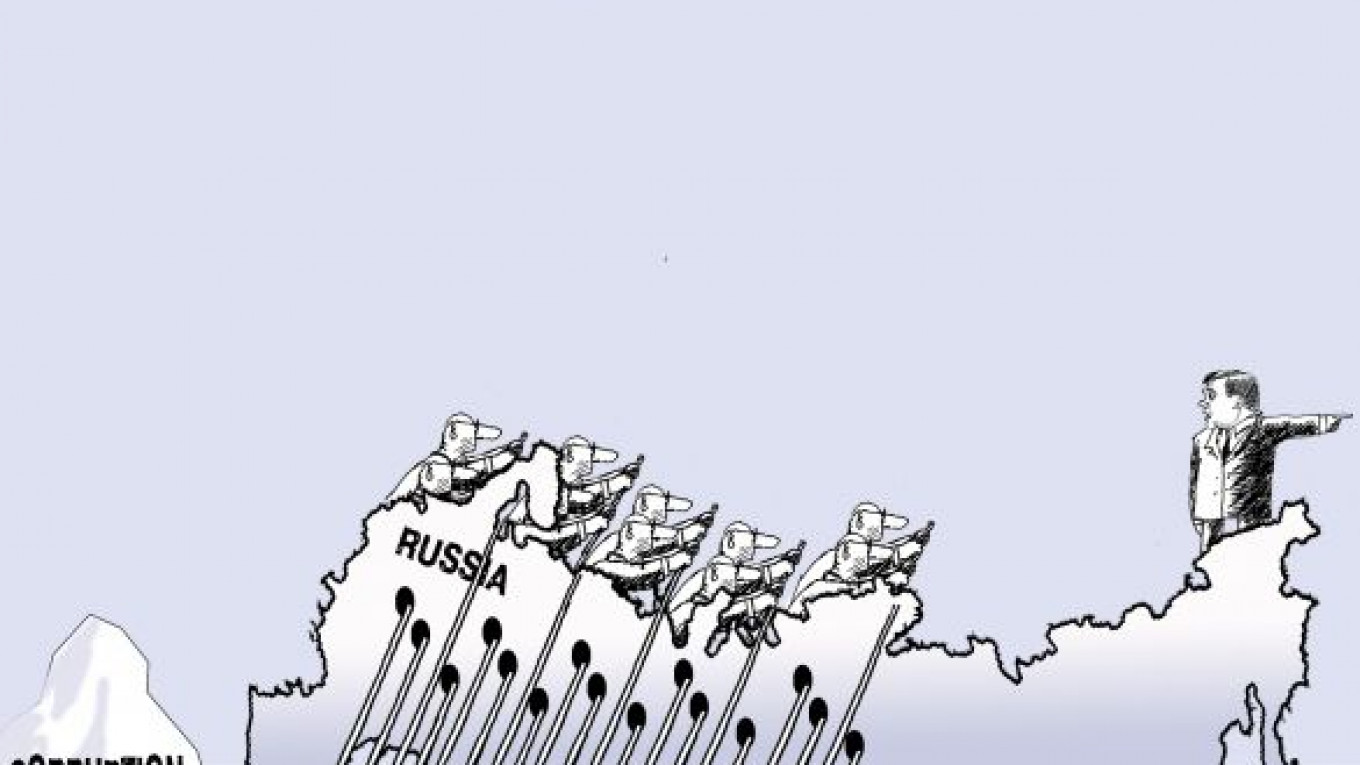

In today’s Russia, a ubiquitous system of corruption has become a substitute for legitimate government. It is a common, acceptable way of doing business every day for the country’s bloated bureaucratic class. And it is extremely profitable; the corruption market is valued by the Indem think tank at more than $300 billion annually.

On a deeper level, corruption has become one of the country’s most distorted national ideologies — one that completely destroys the moral fiber of society. Worst of all, exploited citizens have come to accept corruption as an inevitable component of Russian life that they continually re-elect the very people who are stealing from them.

It is clear why Medvedev has taken an incremental, systematic approach in his fight against corruption. He is trying to raise public awareness by speaking of the need for political competition, judicial reforms and an independent media. Medvedev understands perfectly well that any battle against corruption must be focused on public awareness and grassroots efforts and that this battle is doomed to fail as long as the country is run by a bureaucratic dictatorship.

Most people are more than willing to complain on the Internet or in their kitchens that Medvedev has little chance of succeeding in his fight against corruption. But at the same time, given the chance, they would eagerly snatch a piece of the corruption pie that comes their way. This is exactly why an increasing number of Russians would like to have a government job for themselves and their children. Polls over the last 10 years consistently show that young people entering universities view government jobs as being the most promising — and lucrative, despite the low official salaries.

Willing or not, most Russians are involved to one degree or another in corruption. For example, we might ask whether a friend knows somebody who, for a fee, can give us paperwork showing that our car has passed technical inspection, thereby avoiding many hours of waiting in line. Or we might hunt for someone who can “solve” for a fee a business problem or even secure a government contract for us. Because people have become accustomed to breaking the law ourselves from time to time, they cannot properly formulate their grievances to the authorities. As a result, people don’t demand answers to the questions: Why does Russia have the world’s most expensive yet inferior roads, or why does a country so rich in hydrocarbons have the most expensive gasoline among oil-exporting countries?

The effectiveness of Medvedev’s battle against corruption will always be limited as long as Russians take such a passive position on the issue. Anti-corruption reforms have a chance of being effective only when thousands of people are willing to raise their voices and play an active role in the fight. We had a brief glimpse of this public activism during the protests against the construction of the Moscow-St. Petersburg highway through the Khimki forest. Unfortunately, these protests are few and far between.

Of course, the fact that the authorities decided to go forward with the highway despite the protests doesn’t help the problem of public passivity. It only strengthens the popular belief that public protests against corruption are useless. The notion that corruption originates at the top and that nothing can be changed all too often serves as an excuse for the fear, laziness and indifference pervading society.

If this passivity doesn’t change, Russia faces a very bleak future of moral and social degradation and economic stagnation with the country becoming little more than a raw materials appendage to a more powerful China.

Today, Russians face a choice — not only for themselves, but above all, for their children: to take an active civil stance against corruption or to sit passively on the sidelines and watch as the country dies away slowly but surely.

Kirill Kabanov is chairman of the National Anti-Corruption Committee, a Moscow-based nongovernmental organization.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.