One year has passed since 37-year-old Sergei Magnitsky died while being held on trumped-up charges in a Moscow pretrial detention center. Magnitsky was a lawyer at Firestone Duncan law firm and defended Heritage Capital, once the largest foreign investment fund in Russia. His death, which was caused by the prison authorities’ refusal to provide medical care, falls under the international definition of torture and essentially qualifies as extrajudicial execution.

Magnitsky’s death on Nov. 16. 2009, was followed in April by the death in pretrial detention of Vera Trifonova. She was a seriously ill businesswoman who, given her poor health, should never have been held in prison pending trial. She was mocked by prison officials, who told her that the best way to cure her ills was to sleep standing up.

Most Russians were enraged by these two prison deaths. The sharp public response — particularly among bloggers — prompted President Dmitry Medvedev to examine widespread abuses in pretrial detention centers and in prisons. To Medvedev’s credit, several Moscow prison chiefs and regional Federal Prison Service heads have been fired over the incidents. In addition, Medvedev submitted amendments to the State Duma that ban pre-trial detentions for most economic crimes under Article 33 of the Criminal Code. These detentions have all too often provided Interior Ministry officials opportunities to extort money from individuals accused of crimes.

But the picture is mixed one year later. The Duma approved the president’s amendments, and Medvedev announced major reforms to the Interior Ministry to create a more professional police force. The system has improved by one criterion: Fewer people have been imprisoned as result. In the first nine months of 2010, the number of people sentenced to prison terms dropped by 7.2 percent compared to the same period last year, according to the Supreme Court’s judicial department. More significantly, according to the Federal Penitentiary Service, the total number of accused held in pretrial detention dropped by 10 percent — from 131,400 to 120,100.

At the same time, however, Moscow City chief justice Olga Yegorova said that in the last six months, the court had rejected fewer than 6 percent (36 of 649) petitions for the arrest of businesspeople. The shows in part what many had expected after Medvedev announced the restrictions on holding businesspeople in pretrial detention centers — that the courts have been largely able to bypass the presidential amendments by claiming that the activities of the entrepreneurs were not related to business.

This was clearly demonstrated in the second trial against former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky and his business partner Platon Lebedev. The judge in the case could have denied investigators the right to hold them in pretrial detention on the new charges, although this was an academic issue only since Khodorkovsky and Lebedev would have remained in prison anyway based on their conviction in the first trial.

At the same time, though, the prosecutor took pity on the oligarch and asked the court that he remain only an extra 14 years behind bars, instead of the expected 22 ½ years.

Legal experts and businesspeople say the conveyor belt of arrests of entrepreneurs has only slightly slowed down. The largest reduction of arrests has occurred among small businesses that are a less attractive target for corrupt investigators and prison officials. But the problem remains among larger, more prosperous businesspeople.

The investigation into Magnitsky’s death ran up against stiff opposition from Interior Ministry officials who were implicated by Firestone Duncan, Hermitage and others for embezzling government funds, seizing companies owned by Hermitage and causing Magnitsky’s death. Adding insult to injury, several of these investigators were recently awarded professional honors. In addition, on Monday, Irina Dudukina, a spokeswoman for the Interior Ministry’s Investigative Committee, claimed that it was Magnitsky and Hermitage who had misappropriated 5.4 billion rubles ($230 million) in budgetary funds, not Interior Ministry officials.

Meanwhile, Medvedev continues his legislative battle against widespread abuses by Interior Ministry officials against businesspeople. But it remains to be seen whether new, tougher laws will significantly halt the high level of extortion and number of pretrial detentions of entrepreneurs.

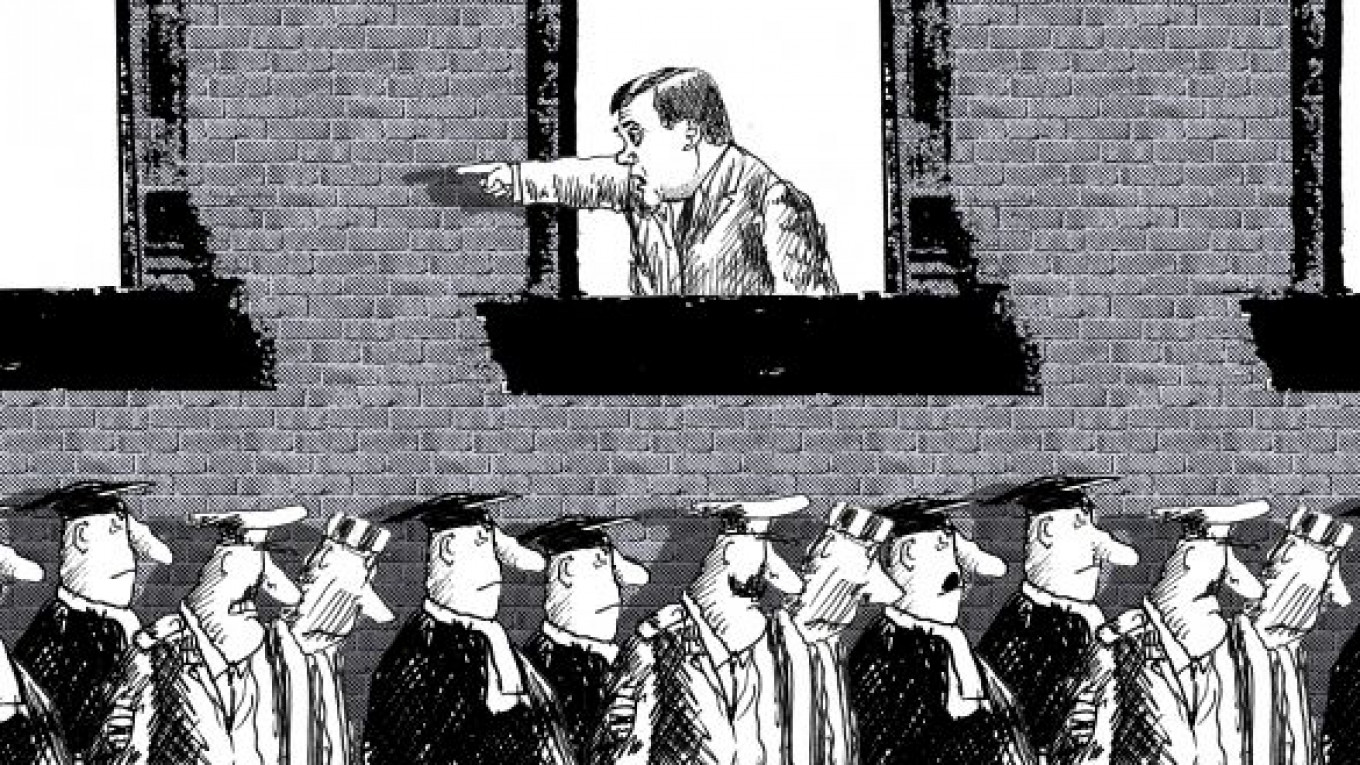

Supreme Court chief justice Vyacheslav Lebedev has not given much reason to be optimistic. He recently said judges still see businesspeople as their “class enemies.” Just like during the worst periods of the Soviet era.

This comment appeared as an editorial in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.