The recent smooth exchange of spies between Russia and the United States appears to demonstrate that the “reset” in relations between the two countries has worked. But Russia has so far done little to reset its relations with Japan. That is a lost opportunity, given Russia’s need to modernize its economy. In addition, it is a grave strategic error in view of the Kremlin’s increasing worries about China’s ambitions in Asia, which includes Russia’s lightly populated Siberian provinces.

In April, China’s navy carried out military exercises near Japan, conducting a live-fire exercise in the East China Sea off the coast of the Zhejiang province, including missile-interception training with new vessels. China’s objectives appear to have been to enhance its navy’s operational capacity, particularly in terms of jamming and electronic warfare, and to test its joint capabilities with the Chinese air force.

Perhaps more important, the Chinese seem to have intended to send a warning signal to U.S. and South Korean naval forces as their joint maneuvers in the Yellow Sea approach. But the Chinese also sent a powerful signal to Japan and Russia.

Meanwhile, Russia is only now beginning to realize that it must be proactive in protecting its national security interests in the Pacific region. The problem is that Russia’s focus is misguided. At the same time China carried out its naval exercises in the Yellow Sea, Russia carried out part of its Vostok 2010 exercises, which involved 1,500 troops, on Etorofu, the largest island among the Russian-occupied Northern Territories of Japan. The entire Vostok 2010 exercise involved more than 20,000 troops.

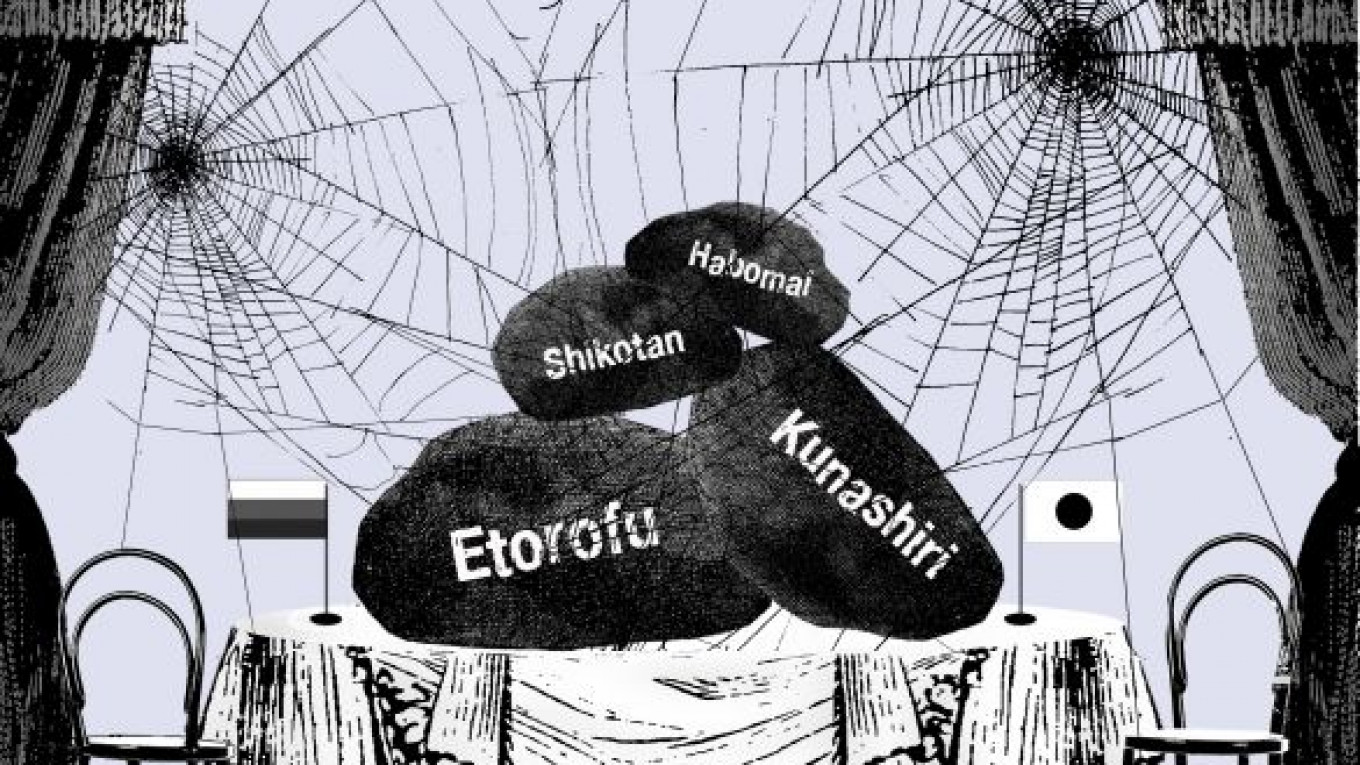

Russia’s illegal occupation of these islands began on Aug. 18, 1945, three days after Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration, which defined the Japanese surrender and ended the Pacific War. Nonetheless, Stalin took advantage of the surrender and ordered the Red Army to invade the Chishima Islands. Russia has occupied Chishima, Southern Karafuto (or Southern Sakhalin) and the islands of Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan and Habomai — which had never been part of the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union at any point in history — ever since.

Indeed, the State Duma recently passed a resolution designating Sept. 2 (instead of Aug. 18) as the anniversary of the “real” end of World War II, effectively making it a day to commemorate the Soviet Union’s victory over Japan — and thus an attempt to undermine Japan’s claim that the occupation of the islands came after the end of the war.

On a recent trip to Vladivostok, President Dmitry Medvedev declared that the social and economic development of the Far East is a national priority. By continuing to maintain its illegal occupation of Japanese territory, however, Russia precludes Japanese involvement in this effort, effectively leaving the Chinese to dominate the region’s development.

Russia’s persistence in its self-defeating occupation is surprising. Indeed, former President Boris Yeltsin came close to recognizing the need to return the Northern Territories to Japan. But a nationalist backlash doomed Yeltsin’s efforts.

There are rumors that Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan’s administration is planning to break the logjam in the Japanese-Russian relationship by appointing Yukio Hatoyama, his predecessor as prime minister, as ambassador to Russia. Hatoyama is the grandson of then-Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama, who signed the Japanese-Soviet Joint Declaration on Oct. 19, 1956, which formally restored diplomatic relations between the two countries and also enabled Japan’s entry into the United Nations. That treaty, however, did not settle the territorial dispute, resolution of which was put off until the conclusion of a permanent peace treaty between Tokyo and Moscow.

In the 1956 declaration, the two countries agreed to negotiate such a treaty, according to which the Soviet Union was to hand over Shikotan and Habomai islands to Japan, while the status of the larger Etorofu and Kunashiri islands would remain unresolved and subject to negotiation.

Japanese public opinion has remained adamant for decades that all four islands belong to Japan, and that no real peace can exist until they are returned. Therefore, sending Hatoyama as ambassador may elicit harsh criticism, since his grandfather once agreed to a peace process that returned only two of the four islands. Many Japanese fear that the grandson may also be prepared to cut another unequal deal.

Fortunately, Japanese voters sense their government’s irresolute nature, delivering it a sharp rebuke in the recent elections to the upper house of Japan’s Diet. But it is not only Japan that needs a government that takes regional security issues seriously. Russia should recognize that it has neglected its position in Asia for too long, and that only when it returns Japan’s Northern Territories can Japanese expertise be brought seriously to bear in developing the Far East.

Only normal bilateral relations will allow the two countries to work together to forge a lasting Asian balance of power. Given his record, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin would not face the type of nationalist backlash Yeltsin confronted if he sought to reach an agreement that restored Japan’s sovereignty over its Northern Territories. Will he have the strategic vision to do so?

Yuriko Koike, former Japanese defense minister and national security adviser, is a member of the opposition in Japan’s Diet. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.