On Sept. 8, Muscovites will head to the polls to elect a new mayor. This will be the first time that they will choose their city boss since 2003.

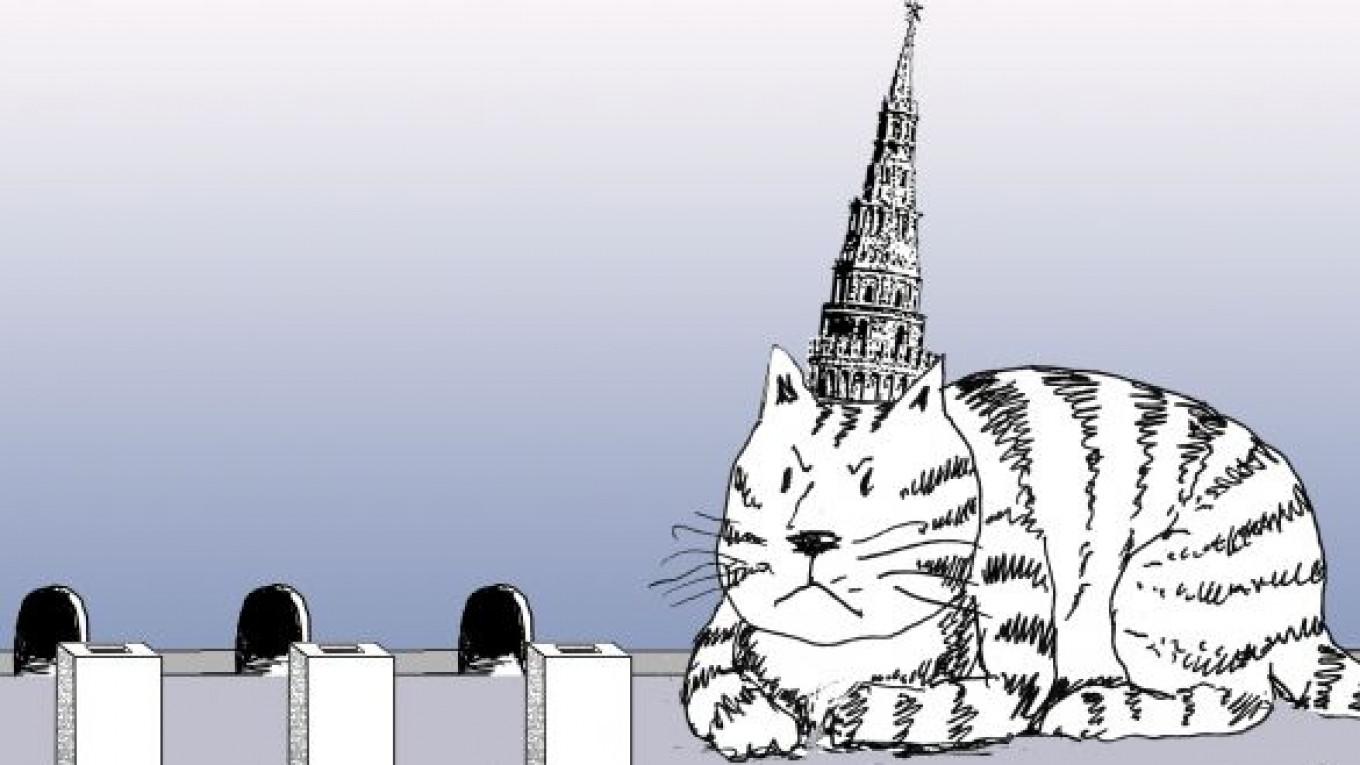

There is little doubt that the ?incumbent, Sergei Sobyanin, will coast to victory. But what is interesting about Russia's elections is not the question of who will win but the more thorny problem of how they will win, using clumsy and outrageous dirty tricks to ensure victory for the pre-?ordained candidate. The events of December 2011 showed that if mishandled, elections can severely undermine the regime's legitimacy and trigger protests.

Russia's "managed democracy" allows opponents to play a walk-on role but only when they have no chance of winning.

The other reason for paying attention to the race is that Moscow occupies a unique position on the Russian political landscape. It is not just that it is Russia's political capital. It is also the center of business, scientific and cultural life. And the degree of influence it exerts over the rest of the far-flung nation is extraordinary. Moscow and the Moscow region account for 10 percent of Russia's population and more than a quarter of its gross domestic product.

Throughout Russia's history, the fate of the country has been decided in the power corridors — and streets — of its capital. Yury Luzhkov, the no-nonsense populist mayor of Moscow from 1992 to 2010, was a prominent figure on the national stage. In 1999, during the transition from President Boris Yeltsin to Vladimir Putin, he came close to toppling the Kremlin power elite as the joint head of a coalition of ?regional leaders.

It is hard to think of another country today where the nation's capital looms so large both in political and economic terms. Even in China, economic decentralization means Beijing has lost influence to mega-cities such as Shanghai, Guangshou and Chongqing.

Another salient feature of Moscow is that its electorate is very distinct from the rest of Russia. Muscovites are wealthier, more liberal and socially?active, willing to protest in the streets to challenge the Kremlin.

All this means that there is a slight chance of a "September surprise" if the Kremlin's cat-and-mouse treatment of opposition leader Alexei Navalny backfires.

Sobyanin, the former governor of Tyumen, was brought to Moscow in 2005 to serve as Putin's chief of staff, moving over to be deputy prime minister when Putin left the presidency in 2008. In 2010, President Dmitry Medvedev fired Luzhkov and ?appointed Sobyanin as his replacement. In response to street protests in late 2011 and throughout 2012, ?Putin changed the rules, restoring direct elections for regional leaders, which he had abolished in 2004.

Sobyanin jumped at the opportunity to boost his legitimacy and get a vote of confidence from his electorate. He stepped down in June to run for a snap election in early September. He even ordered United Russia municipal deputies to sign Navalny's registration petition, part of the "Kremlin filter" requirements for direct elections, to ensure that the opposition leader made it onto the ballot as a candidate.

Russia's system of "managed democracy" sometimes requires that opponents play a walk-on role in the stage-managed elections — but only when they stand no chance of winning, of course. This is a cynical example of what the German Marxist Herbert Marcuse called "repressive tolerance."

Still, at least Sobyanin deserves some credit for wanting to have a rigged election with Navalny in the race. Similarly, former State Duma Deputy Gennady Gudkov, an outspoken Kremlin critic who was kicked out of parliament on shaky grounds, is being allowed to run in the governor's race in the Moscow region. This is slightly better than what the Kremlin siloviki wanted: to keep real opponents off the ballot altogether.

Sobyanin has wanted to run clean elections with restrictions on the use of absentee ballots, a major vehicle for electoral fraud in many regions, cameras in all voting stations and a request for electronic ballot machines.

According to a July 9-11 VTsIOM poll, Sobyanin has a commanding lead with 54 percent support, followed by Navalny with 9 percent. But that was before Navalny's dramatic sentencing and release. On July 25, Synovate Comcon published a poll showing Navalny's support had risen to 15.7 percent.

Presumably, the Kremlin wants to shift the image of Navalny from persecuted martyr to a self-?promoting politician. If he scores in the single digits he will discredit himself as a potential flag-bearer for the opposition in the 2018 presidential election. Given that politics is all about expectations, however, if Navalny wins 20 percent or more of the vote, or if Sobyanin fails to win in the first round by gaining more than 50 percent, it will be perceived as a resounding defeat for the Kremlin.

There is no chance that Sobyanin will participate in televised debates with Navalny during the election campaign. At the same time, the authorities hope to trap Navalny into making extremist statements, perhaps over what to do about migrant workers, that could alienate him from his fellow opposition leaders. This is an issue that has got Navalny into trouble in the past, such as his support for the slogan "Stop Feeding the Caucasus!" In an interview a week ago, Navalny called for requiring residents of the former Soviet republics in Central Asia to obtain visas to enter Russia, although this is something that Putin himself proposed in December.

But it is equally possible that Navalny's populism will strike a chord with an audience beyond the hipster class, or that the Sobyanin team will commit mistakes large enough to trigger an upsurge of sympathy for the opposition.

As former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev painfully discovered, elections are risky business.

Peter Rutland is a professor of government at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.